This webpage was generated automatically, to view the article in its original context you can click the link below:

https://www.ft.com/content/fbc94750-afe3-4eb1-ac48-2e0c7232e965

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website please reach out to us

To claim that we have opened a plethora of new pathways in human health in recent times would be a significant understatement. The mapping of the human genome, quickly succeeded by the capability to modify it, deeper insights into neurodiversity and gender, alongside groundbreaking weight-loss medications that are essentially altering entire populations, are merely a few examples. Not to mention the still only partially explored realm of wellness. If the Covid-19 pandemic questioned what were once widely accepted beliefs about public health, the upcoming year is set to magnify divisions in our comprehension of what defines “healthy,” as disruptors and skeptics adopt new roles of influence. The work featured in this issue confronts inquiries, both minor and major, about what it signifies to inhabit, sustain, endure with, and cherish our bodies.

MIND

Other Joys

By Alice Poyzer

Other Joys represents a collection of works that delves into the fervor of my particular interests as an autistic individual, through self-portraits, documentary images, and crafted visuals.

“Special interests” refers to the intensely concentrated and passionate interests and pastimes that many autistic individuals possess. The sensation associated with one’s special interests is nearly ineffable. It’s a profound feeling of warmth, elation, and thrill that numerous people in the autistic community can identify with. My aim was to convey that emotion.

Although Other Joys was fundamentally designed to illuminate the idea of special interests, it also evolved into a means for me to gain a deeper understanding of my autism.

This project examines my own autistic characteristics, including my necessity for strict routines and my intrinsic capability to perpetually mask my autism. Additionally, the piece advocates for improved representation of autistic individuals, particularly women.

The process of capturing these images granted me a secure environment to express my genuine self, permitting me to unmask and fully embrace my autistic joy. What was previously a dread of being perceived as different and abnormal has now transformed into a celebration of self-acceptance and comprehension.

No animals were harmed during the creation of Alice Poyzer’s project Other Joys. Most of the taxidermy items displayed were sourced from ethical taxidermists and collectors. The larger exhibits are antiques crafted decades before her existence. Neither she nor the current collectors bear responsibility for the original sourcing of these items, and they actively disapprove of ending an animal’s life solely for taxidermy.

It’s Been Pouring

By Rachel Papo

In numerous respects, post-partum depression is no longer a taboo subject. It’s an affliction that occupies a central place in the minds of most expectant mothers as something they dread, and of which they have been informed that counseling and medication can assist. Yet, when I underwent it after having both my children, and when I conversed with other women amidst their struggles, I recognized that there is something we still overlook, or are merely hesitant to confront.

It’s Been Pouring aims to encapsulate the voices of mothers during their most challenging times. I frequently describe the two periods in my life when I dealt with post-partum depression as being overtaken by a dark force that commandeered my mind and body. I was present, aware of everything happening, but utterly powerless, incapable of acting until that dark force departed.

This collection of photographs and interviews illuminates women’s experiences with post-partum depression, highlighting the unbearable strain that exists between the miracle of childbirth and the horror that ensues, guiding the viewer through a narrative of hopelessness.

Post-partum depression, although acknowledged and defined as a medical condition, is also associated with women’s responses to the societal circumstances tied to motherhood. This includes their position within society, societal expectations, their own anticipations, and their erosion of identity. We are still far from recognizing the profound challenges a mother faces when her internal experiences do not align with society’s expectations of her as a joyful mother bonded to her newborn, a realization that only intensifies the daily obstacles she inevitably encounters. Many

of the mothers I spoke with, whose expressions contribute significantly to the project, experienced feelings of isolation in this battle.

Julia

I was taken aback that I had awaited this child for such an extended period, everything was prepared and lovely, yet I suddenly felt I had made a tremendous error. I wondered, “What is wrong with me? You have all that you desired.” My spouse would remind me, “This is what we wished for; he’s healthy, this is what we longed for,” and I felt incredibly selfish for thinking, “Well, I don’t want it any longer.”

Brooke

Oblivious. If I had to pick one term to define that period — I kind of shut down in a particular way.

Nikki

I would consistently wear these cheerful facade masks, acting as if all was well. Inside, I was suffering immensely.

“It’s Been Pouring” is published by Kehrer Verlag

All I Know

By Becky Warnock

This project was developed in partnership with a group at Mountsfield Recovery House in Lewisham, south London, during a three-month artist residency earlier this year. The Recovery House serves as a support center for individuals in crisis, focusing on holistic care and closely collaborating with clinical services.

My artistic practice explores the boundaries of spoken and written language when depicting the experience of mental health struggles. Terms often seem inadequate to capture the spectrum of emotions, or lack thereof, that we confront when enduring episodes of depression, psychosis, or other issues. For me, the photography studio serves as a performance space. It’s a setting to experiment, to explore, to engage our bodies in thought rather than just our minds.

Music has been an essential source of comfort and connection. At the Recovery House, we created a playlist where each participant contributes a song as a welcoming gesture for the next individual arriving at the center.

This playlist facilitated the creation of the visuals — they were crafted while the music played.

The exhibition will be showcased in the communal areas of the center next year, accompanied by the soundtrack that complements the imagery.

The artist-in-residence program is facilitated by Bethlem Gallery and supported by Maudsley Charity

One year of therapy

By Ryan Prince

My path into therapy initiated in 2018, following the end of a long-standing relationship that left me feeling adrift. What began as a single complimentary session evolved into weekly appointments over a span of four years.

The choice to commence documenting my therapy encounters emerged while pursuing my master’s degree in documentary photography at the University of Westminster. My work fundamentally seeks to reveal and explore what it signifies to be a Black Briton in contemporary society. Much of this involves challenging stereotypes and normalizing lived realities.

Throughout my MA, I devoted significant time capturing images of my family, making it feel like a natural evolution to focus the lens on myself and document what was becoming a crucial aspect of my personal development. There exists a stigma within a large portion of the Black community, particularly the Jamaican community from which I hail, where mental health is often overlooked. It’s approached as if it’s non-existent. My aspiration for this project is simply to illustrate what therapy appears to be, and to demonstrate that it’s entirely normal and, at least for me, an incredibly advantageous process.

BODY

Metamorphosis

By Ngadi Smart

Metamorphosis is an anthology of photographic collages delving into loss and mourning. One of my most significant encounters with loss occurred in my late twenties when I received a diagnosis of oestrogen-positive breast cancer. The news struck my family and me like a heavy blow.

The semi-nude self-portraits are placed alongside images of early 20th-century African females, African artifacts, and the planet Venus (named after the deity of affection and fertility), along with western symbols of fertility such as flowers, the Venus of Willendorf, and the hue blue associated with the Virgin Mary. Flowers are prominently featured in this collection, as they symbolize loss but also embody life and sensuality.

I investigate the themes of death and renewal I experienced through the loss of my pre-cancer existence and fertility. I am no longer the same individual, yet I honor all it took to navigate this journey. I celebrate the strength of ancestral connections, like that of my late grandmother, who succumbed to the identical illness, and those of the African women integrated here with me, whose narratives remain unheard from their own voices.

Loss ignited within me a power I was unaware I had. It demonstrated to me the significance of existence and completely reshaped me, both physically and mentally. A metamorphosis.

leave-taking

By Mari Katayama

I’ve never offered for sale, nor discarded, items I’ve created. These items define the artist I am. Nevertheless, I chose to donate them to a public collection. The leave-taking series captures photographs of those items prior to their shipment. Extended exposures, along with me engaging the shutter, leave a ghostly impression of my body in motion.

When I describe my work, I often state that my body serves merely as a mannequin for the objects. Perhaps I am dodging the confrontation with my self-image. I interact with society through these objects. I become increasingly aware of the “correctness” demanded in social settings. The world is engineered for “correct bodies”, without which one cannot compete.

The items have departed. Once leave-taking was finalized, my emotions too were resolved. Life continues. Our thoughts and bodies evolve. “Correctness” is simply a construct humans devised for ease. Times also transform. Was the “correct body” that I longed for truly what I desired? Through my work, the notion of the body becomes indistinct.

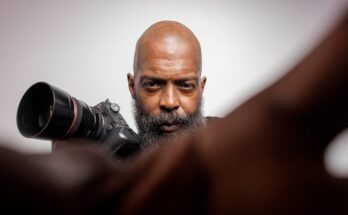

Dex Diggler

By Dexter McLean

I have always sensed that society treats me differently due to my cerebral palsy, my wheelchair use, and my speech impediment. When I was in my final year of university, I recall discussing with friends about never having had a girlfriend and worrying that I might end up alone, without a family of my own. All you ever see in the media are images of people with “ideal bodies.” This makes me feel as if there is something amiss with my body or something wrong with me as a person. This has fueled my anger toward society and much of mainstream media. This project is a result of that indignation. It represents my way of resisting the shame imposed by society on individuals with disabilities.

Growing up in Jamaica during the 1990s, when individuals with disabilities were frequently termed as “handicapped,” there were minimal specialized resources, and I was made to traverse on my knees and treated differently from my peers. This constant reminder of my physical difference intensified as I matured, causing my body confidence to diminish. This project serves as a healing exploration of my own form and sensuality, reaffirming the confidence I possess today. I aim to illustrate that the bodies and sexuality of disabled individuals have been significantly overlooked in both art and media, and that having a physical disability does not lessen a person’s desires or needs.

By combining concepts from classical nude sculpture, body representation in painting, boudoir photography, and pornography aesthetics, I aspire to challenge perceptions surrounding what it signifies to be a young, Black, sexually active disabled man in the 21st century.

Sokohi

By Moe Suzuki

Despite its extensive history and being the most prevalent cause of visual impairment in Japan, glaucoma remains poorly understood, and treatments are not always fruitful. My father’s glaucoma exemplifies such a case. Fourteen years of daily medication, alongside surgery, has not entirely managed his elevated eye pressure, which has led to gradual yet progressive defects in his visual field. Each day, he awakens to a slightly dimmer world, and when he attempts to grasp something, his hands often reach for thin air.

My father maintained journals throughout much of his life. He captured photographs while traveling. Moreover, throughout nearly 50 years in his editing career, he was surrounded by books and writing. However, due to his glaucoma, he can no longer read or write.

Although he seems to accept his destiny calmly as his sight dwindles, there are instances in which he clings in desperation to his fading vision, as though fighting to prevent it from vanishing entirely. Concurrently, he erects a barrier around himself to shield from the sympathy of those who can see what he cannot, and who cannot grasp what he can. His journey towards blindness oscillates between brightness and shadow, similar to the waves pushing and pulling towards the shore.

“Sokohi” is published by Chose

Commune

Ill in Bed

By Cheryl Newman

Ill in Bed represents a series of vernacular snapshots that I started purchasing in 2015 from flea markets, antique stores, and online platforms, which collectively examine the photographic perspective. Imbalanced power relationships are inherent in a significant portion of portrait photography, yet when the subject of the photographer is a female or girl confined to her bed, the imbalance is exacerbated.

Upon reaching her 20th birthday, my daughter Mimi experienced a disability. I commenced photographing her, yet it was distressing as I felt I was becoming an accomplice in the voyeuristic attitude towards those with disabilities. Academic Katherine Byrne elucidates how invalidism became a lifestyle for women suffering from tuberculosis in the 19th century, as it was a means to exhibit the most sought-after feminine traits; namely purity, passivity, and a readiness to sacrifice oneself for others, predominantly men. Through this collection of anonymous portraits, I reconnect with my experiences with my daughter and face the contemporary legacy of these historical sentiments towards female patients.

SOUL

You Experienced the Roots Grow

By Sabine Hess

“I grasp your hand and, cautiously, seek to capture it. Imprint on my mind the sensation of your wrinkled skin, the heat of your touch, the manner in which your fingers envelop mine.”

I penned those phrases about my father. Reflecting upon this period now, I sense that I was striving to comprehend my mixed emotions, as my sister entered motherhood around the same time my father’s health deteriorated.

Observing a new life develop while another weakened reconfigured my perception of time. It became unmistakably clear how delicate life truly is. At times, when home felt too stifling, nature provided my mind a tranquil refuge. The gradual growth and decay of the forest mirrored the illness that was consuming my existence as I knew it.

Following my father’s death, I experienced grief in various forms, and occasionally my remembrance of him felt more distant than I was prepared to acknowledge. Yet throughout this journey, I also discovered hope and resilience in articulating a story so intimate. Today, the same forest—now with fresh leaves and branches—continues to reveal how life after loss can remain possible.

“You Experienced the Roots Grow” is released by Ciao Press in collaboration with Witty Books

The Radiance in the Dusk

By Jialin Yan

In China, so-called senior universities, many of which are operated by the Open University of China, specifically target older students. Numerous such institutions exist across the nation, and they do not impose particular entrance requirements.

Older individuals arrive to enhance their lives and seek personal value. Approximately 70 percent of them are women. Due to the familial duties typically assumed by women in China, many seldom find personal time until their careers conclude and their families reach an older age. It is only then they enroll in these universities.

My mother registered for a course in Chinese calligraphy at the Open University of Fujian following her retirement as an account manager. I became intrigued and began to follow her and her classmates to understand their motivations and chronicle their experiences.

Mother’s Healing

By Mathias de Lattre

My fascination with psychedelics emerged about a decade ago. As I delved deeper into the various applications of psychedelics in treatment, I also observed my mother’s spiral into severe depression. She was diagnosed with bipolar disorder in her late forties.

Having grown up with her, I witnessed her often intense mood fluctuations, which could happen daily. The numerous medications she ingested daily bewildered her without stabilizing her emotions. The side effects compromised her bones, teeth, and immune system, and triggered various allergies. She began to lose her memory and her focus. I feared that—at the least—she would spend the rest of her life in a psychiatric facility.

Once I became confident in the therapeutic potential of the medicinal psychedelics I was studying, I decided to discuss psychedelic-assisted therapy with my mother. We established a low-dosage regimen, and although each individual responds differently, and exhaustive tests on the various types of bipolar disorder are lacking,exist, her situation has significantly progressed due to this therapy.

“Mother’s Therapy” is issued by Eriskay Connection

Food is the Ultimate Narrator

By Giles Duley

Each photograph holds a recollection, a prompt for a moment and place now gone. The borscht on Luba’s dining table, situated in her now ruined home near Avdiivka. The coffee mugs resting in Mahmoud Khader’s apartment in Gaza. The green soup prepared by Deborah in the Sudanese refugee camp.

In Mosul in 2017, amidst the chaos of battle, I encountered a family torn apart by the conflict. Laila, the matriarch of the home, wailed as she pointed out where her husband had been slain, where her son-in-law perished, and ultimately, where her daughter was shot in the kitchen.

At that instant, the act of photography felt unnecessary. Instead, I inquired if I could prepare a meal with her. I returned with a frozen chicken and a sack of rice, the only items I could uncover in that devastated city.

Now, I always aim to share a meal with families and communities before capturing images. It’s my method of connecting, through the finest storyteller. Food stands in stark contrast to war. While conflict disintegrates communities and embodies animosity at its core, food unites people and expresses affection. In food, I discover my tranquility.

Stay updated on our most recent stories — follow FT Weekend Magazine on X and FT Weekend on Instagram

This page was generated programmatically; to view the article in its original format, you can follow the link below:

https://www.ft.com/content/fbc94750-afe3-4eb1-ac48-2e0c7232e965

and if you wish to eliminate this article from our site, please reach out to us