This webpage was generated programmatically; to view the article in its original setting, you can follow the link below:

https://www.astronomy.com/science/unusual-spiral-quasar-seen-dancing-with-a-companion/

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website, please get in touch with us

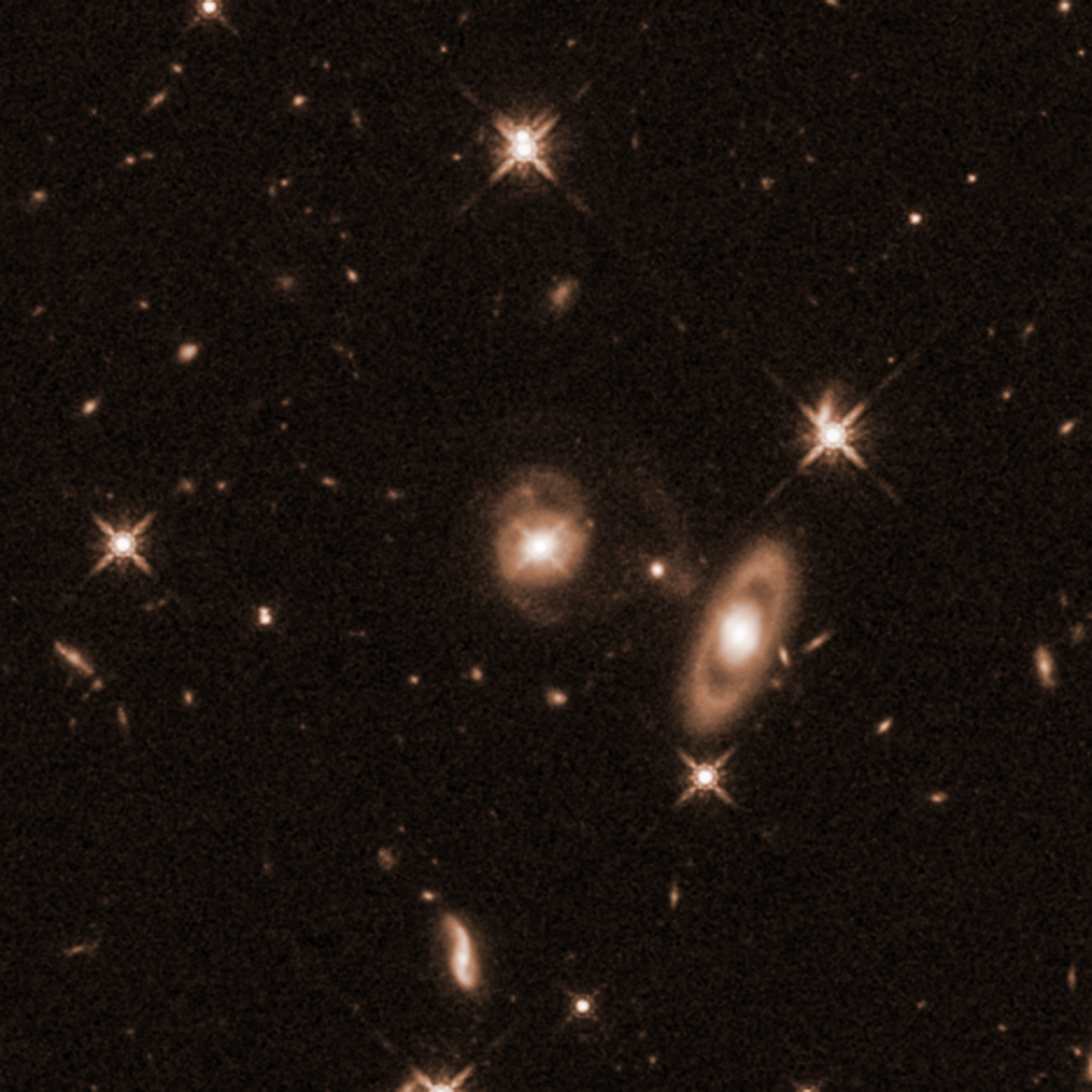

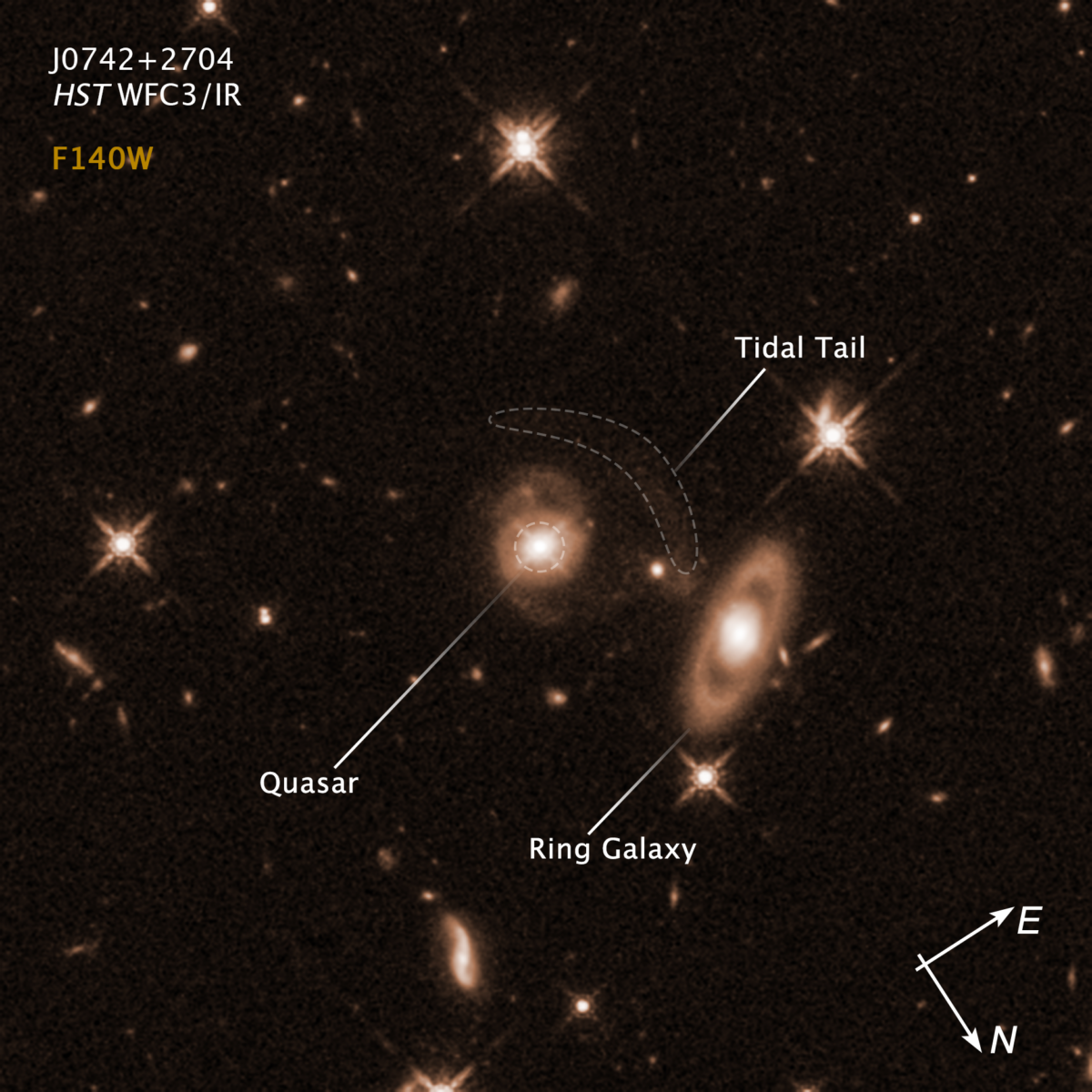

The quasar J0742+2704 (center) has a small companion galaxy positioned just to the right, located between the quasar and a ring galaxy. Credit: NASA, ESA, Kristina Nyland (U.S. Naval Research Laboratory). Image processing: Joseph DePasquale (STScI)

The jets emitted by a supermassive black hole represent one of the most remarkable phenomena in the universe — and simultaneously one of its greatest enigmas. These streams of ionized matter erupt from the cores of galaxies at speeds nearing that of light. The mechanisms by which these black holes capture and concentrate that energy remain a topic of heated debate.

In recent years, astronomers have achieved success in identifying galaxies with central black holes that have only recently become active, hoping to uncover remnant clues about what ignited them. During this month’s American Astronomical Society (AAS) winter meeting in National Harbor, Maryland, researchers shared a fascinating example — a massive supermassive black hole emitting a jet from the core of a galaxy exhibiting visible spiral structure.

The entity known as J0742+2704 is categorized as a quasar, a specific type of active galaxy whose jets are so luminous that they overshadow the galaxy itself, making it appear as a star-like point in images. (The term “quasar” originates from the descriptive phrase “quasi-stellar object.”) Galaxies with such powerful jets are generally old, elliptical, and devoid of features, having exhausted their youthful spiral structure through tumultuous mergers with other galaxies. However, when astronomer Olivia Achenbach examined data from the Hubble Space Telescope, her analysis clearly showcased spiral arms encircling it — suggesting that it has not yet undergone the gravitational disruption of a significant merger.

“At first, I was convinced I’d completely botched the analysis,” stated Achenbach, a midshipman at the U.S. Naval Academy, during a press conference on Jan. 13. She received guidance from astronomer Kristina Nyland of the Naval Research Laboratory. “We both anticipated that with a supermassive black hole of such scale at the center, we would observe an elliptical galaxy.”

This discovery adds a new layer to an ongoing discussion regarding how supermassive black holes and their host galaxies develop, advance, and interact. The prevailing theory — that black holes commence feeding and activate their jets during galaxy mergers — is known as the major merger model. “To obtain such a clear and unmistakable result that appears to contradict the major merger model is exceptionally thrilling,” remarks Rachel Cionitti, an astronomer and graduate student at the University of Missouri in Kansas City, who did not participate in the research.

A cosmic ballet

According to the major merger model, the majority of galaxies initially possess spiral shapes, but ultimately lose them as they expand and combine. A significant merger prompts star formation, yet it also stirs the galaxies into large elliptical shapes. This process likewise leads to stars, gas, and dust descending into the central black holes, which are simultaneously growing and merging. Subsequently, when the black holes start to consume, they incite activities like jets and intense radio emissions from just outside their event horizons.

J0742+2704 introduces complexity to that narrative. It harbors a large central black hole weighing in at 400 million solar masses. However, its jets have only recently activated — they were absent in similar observations two decades ago. Furthermore, the spiral arms identified by Achenbach are a definitive sign that it has not been subjected to a major merger. “No galaxy emerging from a merger would retain a pristine spiral structure,” Cionitti states.

Rather, the jets could be instigated by interactions with a smaller companion galaxy. In the Hubble image, a ring-shaped galaxy is visible to the right of J0742+2704, with the smaller companion positioned between them. There are also indications of a potential tidal tail — a stream of stars being torn away as J0742+2704 and the companion engage with one another.

Cionitti also believes that interactions are essential to illuminating the jets’ activity. She suggests that the “little baby galaxy” is likely “disturbing the gas” within its host galaxy, resulting in a loss of momentum that drives matter toward the center. Nevertheless, she emphasizes, “numerous questions regarding that mechanism remain unanswered.”

Supporting this view, Achenbach highlights observations from the Low-Frequency Array (LOFAR), a network of radio telescopes across Europe. They provided evidence of past jet activity — extensive lobes of radio emissions flanking the galaxy. These may represent the remnants of earlier jets that encountered intergalactic gas; those jets eventually faded and ceased before reactivating in the last twenty years.

The hypothesis presented by Achenbach and Nyland suggests that the jets of J0742+2704 are repeatedly initiated as this companion orbits its larger neighbor — what Achenbach refers to as a “cosmic dance” — with no significant merger necessary.

Questions about major mergers

Cionitti presented findings at the AAS meeting that also challenge the major merger model.

The onset of galaxy mergers incites bursts of star formation. These hot young stars predominantly emit blue light, but the major merger model posits they are initially obscured by dust that has been kicked up. Viewed through this dusty shroud, the galaxy appears redder. However, once a galaxy’s jets activate, the winds from the galactic center disperse that dust, gradually revealing a bluer hue as more light from newly formed stars becomes visible.

However, Cionitti and her collaborating scientists observed that among galaxies at the same distance, those that are brighter in redder light tend to be more massive than those that shine brighter in bluer light. This contradicts what would be expected if galaxies transition from red to blue during a merger.

Overall, Cionitti remarks that there is “just a vast amount of confusion” among astronomers attempting to ascertain how active galaxies and their central black holes co-evolve (or not). For Cionitti, Achenbach’s research is exciting because it illustrates that there are multiple “evolutionary pathways, that there’s not just one” for how galaxies’ central black holes become active — a phenomenon referred to as an active galactic nucleus (AGN).

“I truly believe there’s much more occurring beneath the surface of the AGN-quasar umbrella than we currently realize,” Cionitti concludes.

This webpage was generated programmatically; to view the article in its original setting, you can follow the link below:

https://www.astronomy.com/science/unusual-spiral-quasar-seen-dancing-with-a-companion/

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website, please get in touch with us