This webpage was generated programmatically. To view the article in its original site, please visit the link below:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/fossilized-poop-reveals-how-extinct-flightless-birds-helped-spread-new-zealands-colorful-fungi-180985853/

and if you wish to have this article removed from our site, please get in touch with us

:focal(956x537:957x538)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/49/3d/493dd162-cf0a-42c6-bbcf-00712c3dc432/moa_coprolite_unknown_species_from_dart_river_valley_photo_credit_janet_wilmshurst.png)

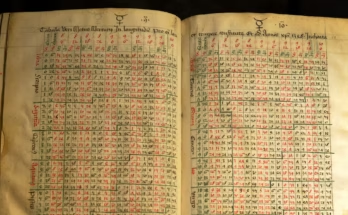

Fossilized excrement, also referred to as coprolites, are assisting researchers in New Zealand to look back in history.

Janet Wilmshurst

Researchers can gather a wealth of information about extinct species by examining their footprints, skeletal remains, and even dental structures. However, while these remnants can provide valuable insights, they do not always offer a thorough understanding of an ancient organism’s feeding habits or actions. To obtain that information, scientists frequently turn to another resource: fossilized excrement.

Fossilized feces—commonly known as “coprolites”—can provide insights into “the final day or two [of] the behavior of an animal from hundreds of thousands or millions of years ago,” explains Alexander Boast, a paleoecologist at Manaaki Whenua – Landcare Research, in a conversation with Cosmos’ Evrim Yazgin.

For instance, Boast and a team of researchers are utilizing fossilized dung to uncover more about the diets of the extinct flightless avians known as moa that once lived in New Zealand. The study of coprolites allowed them to verify that moa dined on vibrant native fungi—and, in doing this, the ostrich-like animals may have played a role in preserving healthy forests on the South Pacific isle.

Their discoveries are detailed in a recent paper published last week in the journal Biology Letters.

Moa—large, flightless birds resembling ostriches—once inhabited New Zealand. However, they were driven to extinction by human hunting approximately 600 years ago. John Megahan via Wikimedia Commons under CC BY 2.5/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/df/c6/dfc6be22-097a-466b-9f56-cef16efc89ec/1024px-giant_haasts_eagle_attacking_new_zealand_moa.jpg)

Fungi are crucial in numerous ecosystems. By decomposing organic material, they replenish nutrients in the soil. Moreover, by forming partnerships with tree roots, they protect plants from harmful intruders and aid them in nutrient and water absorption.

A variety of fungi depend on animals for distribution and growth. These forms generate unappealing yet palatable fruiting bodies called truffles, which mammals such as dogs or wild boars locate by scent—subsequently digging them up and consuming them. In the process, these animals carry the fungi’s spores to new locations when they excrete.

However, prior to human colonization, New Zealand did not possess any mammals roaming around and feasting on truffles—the island’s only indigenous mammal species are bats and aquatic animals. This led scientists to ponder: How were the fungi being dispersed?

They speculated whether the island’s avian species, including moa, could have contributed to this process. Some native, truffle-like fungi produce strikingly colored fruiting bodies that appear in shades of blue, pink, and purple—and to moa, known for consuming fruit, these fungi might appear similar to berries.

“Birds possess remarkable color vision and primarily forage using their sight,” Boast states to Cosmos. “Thus, it seems there has been some form of mimicry. Essentially, these fungi resemble berries on the forest floor, which is extraordinary.”

Certain native fungi species, such as Gallacea scleroderma (shown here), develop vivid fruiting bodies. Noah Siegel/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/8d/75/8d757b39-91c5-4cef-ad39-b80930a41e5f/gallacea_scleroderma_arthurs_pass_photo_credit_noah_siegel.jpg)

Validating that the extinct birds consumed and disseminated these native fungi proved challenging—until scientists came across the “coprolite of destiny,” as Boast describes during an exchange with Science’s Phie Jacobs. His team was exploring a cave when they uncovered a piece of fossilized dung lodged in a crevice.

This specimen was from an upland moa (Megalapteryx didinus), one of the nine species of moa that existed in New Zealand prior to humans hunting them to extinction around 600 years ago. Weighing between 30 and 140 pounds, upland moa were among the smallest of the moa species, according to reports by Stuff’s Caron Copek.

The team also located a second upland moa coprolite preserved in a museum. Upon analyzing samples taken from the two fossilized feces, they discovered spores and DNA from the colorful native fungi—confirming their initial theory that moa ingested the fungi and facilitated their spread.

“At this point, it’s quite clear that [moa] were absolutely, certainly consuming these things,” Boast informs Science.

The brilliantly colored fruiting bodies of native fungal species, including Gallacea scleroderma, may have been visually appealing to the extinct flightless birds known as moa. Joseph Pallante/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/b1/fc/b1fc4c03-96c5-4b19-b1bd-7423a1c939f4/gallacea_scleroderma_te_anau_photo_credit_joseph_pallante.jpg)

Now, with the moa no longer existing, it is likely that the fungi are not being dispersed as frequently or widely.

Following the colonization of New Zealand by Europeans, various non-indigenous mammals, such as possums, deer, wallabies, and feral pigs, were brought to the island. However, these creatures are not inclined to consume the brightly colored native fungal fruiting bodies—they prefer odoriferous, non-native truffles instead. These introduced fungi, in turn, facilitate the growth of alien trees that may outcompete indigenous trees like the southern beech.

This situation could lead to significant consequences for the forest ecosystems of New Zealand, although researchers are continuing to explore the potential cascading effects of the extinction of the moa.

“It’s fascinating to examine a historical ecosystem, but we are striving to comprehend the complexity of past ecosystems and the long-term legacy effects that extinction might entail,” Boast explains to Cosmos. “This is precisely why we view this research as critically important.”

Matthew Smith, a mycologist at the University of Florida who did not participate in the study, posits that the native fungi may retain potential for survival, even without the moa for spore dispersal: “Fungi are quite resilient,” he remarks to Science. “I wouldn’t discount their survival.”

This page was generated programmatically; to view the article in its original form, you can visit the link below:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/fossilized-poop-reveals-how-extinct-flightless-birds-helped-spread-new-zealands-colorful-fungi-180985853/

and if you wish to remove this article from our website, please get in touch with us