This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://insidestory.org.au/moments-of-exposure/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

In his new assortment of eight wide-ranging essays, the distinguished photographer Michael Collins makes a plea for the artwork of shut remark. The viewer’s function is to look, not merely to look after which transfer on, perpetually beneath stress to get to the following picture. “Photography’s ubiquity is its nemesis,” he laments, as a result of ubiquity begets scrolling, and scrolling is the enemy of reflection.

This distinction between the rewards of consideration to the only picture and the fact of photographic abundance kinds the thread that runs by means of Blind Corners: Essays on Photography. That doesn’t imply each picture deserves the sort of shut consideration Collins advocates. Most pictures, he says, by which he means most pictures right this moment, “is the antithesis of photography itself.” It grows “louder and dumber.” It shouts with out actually saying something.

Collins favours the {photograph} that has one thing to say, that doesn’t shout however leaves us, as viewers, to detect the sound behind the silence. But he’s much less clear about how we are going to know after we come throughout such a picture, apart from that there’s a magic to it. On the opposite hand, he is superb on the magic a part of the equation, on what occurs after we set off on a quest — an finally hopeless quest — to know and perceive the world a singular picture represents.

The magic invitations us in and leads us to surprise and to take a position. In the primary essay of the gathering, Collins appears very fastidiously certainly at a picture of Coronation Day, Tenby, 1953. His eye is first drawn to it when he spots a photocopy pinned to the wall in a pictures store. The image was taken many years earlier than by the proprietor, Graham Hughes, and exhibits a gaggle of 100 or so individuals posed on a hillside, introduced collectively to create a marker of a day of celebration and commemoration.

Hughes is unable to find a print of the image, however after rummaging round in drawers he does recuperate the glass destructive. Collins is charmed by the physicality of it. There is a protracted scratch on the destructive, and a chip within the emulsion, however these too are a part of its historical past, and he recognises that, blemishes however, it’ll “yield a superb print.”

Wonder turning to interrogation: Graham Hughes’s Coronation Day, Tenby, 1953 (above and, magnified by Michael Collins, under). © Graham Hughes

By technique of a sequence of accelerating magnifications, Collins deploys right this moment’s know-how to disclose a stage of element in Coronation Day that an authentic, bodily print would hold hidden. The result’s a classy exploration of what’s gained and what’s misplaced by this strategy of magnification, and at what level “wonder” turns into “interrogation.” Does wanting too intently jeopardise the magic?

Magnification, courtesy of applied sciences developed lengthy after the {photograph} was taken, permits the viewer to zero in on people and to take a position on particular person lives. We should base that hypothesis on the moment recorded by the picture. “A photograph does not acknowledge what preceded or followed the exposure.” It does, nonetheless, invite us to think about the earlier than and after of what we see in entrance of us.

“Photography’s gift comes with despair,” says Collins — despair over what has not been captured by the digital camera, of what’s exterior the body, of what occurred simply earlier than or simply after, of what that expression actually means. Is it anger, for instance, or indigestion?

This impulse to think about context, which so fascinates Collins, is probably what drives the present vogue for animating pictures, turning them into quick movies or gif like loops. A person in a prime hat all of a sudden takes the hat off, places it on, doffs it repeatedly. His eyes transfer, his expression adjustments, and but he doesn’t come to life. Instead, the magic of the nonetheless picture evaporates, and we’re left feeling one way or the other disillusioned.

The stillness supplies the magic. Our have to know, hopeless although it might finally be, is what actually retains us wanting, and what actually animates the picture. {A photograph}, like a biography, can by no means inform us sufficient. We all the time wish to know extra. As Collins demonstrates by his detailed speculations on the inhabitants of Coronation Day, the truth that the individuals within the image are immobile, silent and monochrome encourages us to assume we’re tantalisingly inside attain of realizing them.

For Collins, {a photograph}’s energy lies in its very singularity. This will not be a modern view. We are rather more attuned right this moment to take a look at pictures in relation to 1 one other, not simply on gallery partitions however in digital archives and curated collections. This tendency to bundle pictures collectively, with the concept every picture has the facility to light up the others, is probably traceable, partly a minimum of, to the phenomenon of over-abundance and the query of what to do with all these photographs. But clearly there may be extra to it than that.

The photographer Joel Meyerowitz, in a latest challenge undertaken in collaboration with the platform Fellowship (“dedicated to supporting… artists who explore the boundaries of art using innovative technologies”), displays on the differing impacts of the singular picture and the sequence. “Besides delighting in the purity of the single image,” he says, “photographs can also act like an alphabet of meanings when seen in relationships with other photographs.”

Meyerowitz’s challenge, entitled Sequels, goals to reanimate his sixty-year archive utilizing blockchain know-how to “play with how images interconnect,” but in addition to ask viewers and collectors to assemble their very own sequences of Meyerowitz pictures. By constructing their very own collections, viewers can create new and sudden — and to some extent, a minimum of, personalised — meanings.

Collins will not be so certain concerning the energy of sequencing. He thinks it might probably muddy the waters. “Photography is a prisoner of seriality,” he writes. True, pictures can inform each other, he goes on to acknowledge. Seen collectively, they’ll carry out “motifs and meanings that might otherwise be more mute.” But this reads extra as a concession than a sturdy endorsement. We don’t really feel that his coronary heart is in it. To get probably the most out of {a photograph}, he concludes, we should focus as viewers on its “inimitable uniqueness.”

Both Meyerowitz and Collins, of their differing methods, spotlight the function of the viewer in extracting which means from a picture, the viewer appearing as a co-creator. For Meyerowitz, in step with the instances, this participative function is enacted by means of the method of meeting and curation, the association of pictures to boost which means. For Collins, against this, the important relationship, and arising out of it the development of which means, is strictly one to 1 — between the only picture and the viewer.

In the essay “Personal Picture Show,” which acts as a sort of companion piece to Coronation Day, Tenby, Collins turns his consideration from group to particular person portraiture. In doing so, he reserves his highest regard for these photographers who seize the humanity of the topic or, put one other manner, supply the viewer a pathway to that humanity.

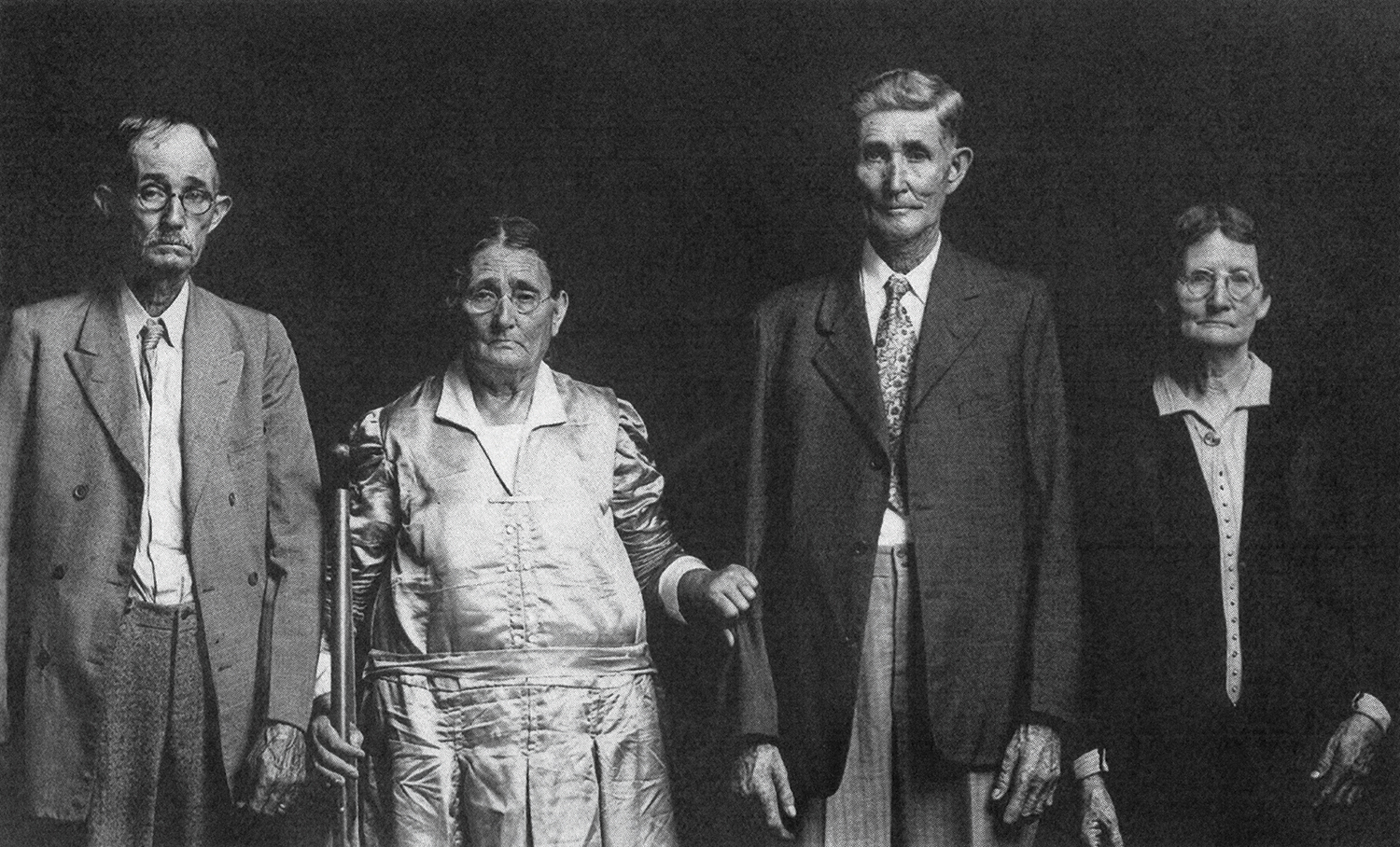

The digital camera acts as a bodily barrier — Collins calls it a “shield” at one level — between photographer and topic, and whereas some photographers can sidestep or transcend that barrier, others exploit it. For Collins, the portraits made by celebrated mid-century photographers corresponding to Mike Disfarmer and Diane Arbus successfully embalm their topics, treating them as victims of the digital camera quite than companions with it. They will not be solely topics, however subjected too.

“Like ghosts”: a Mike Disfarmer group portrait from c. 1930.

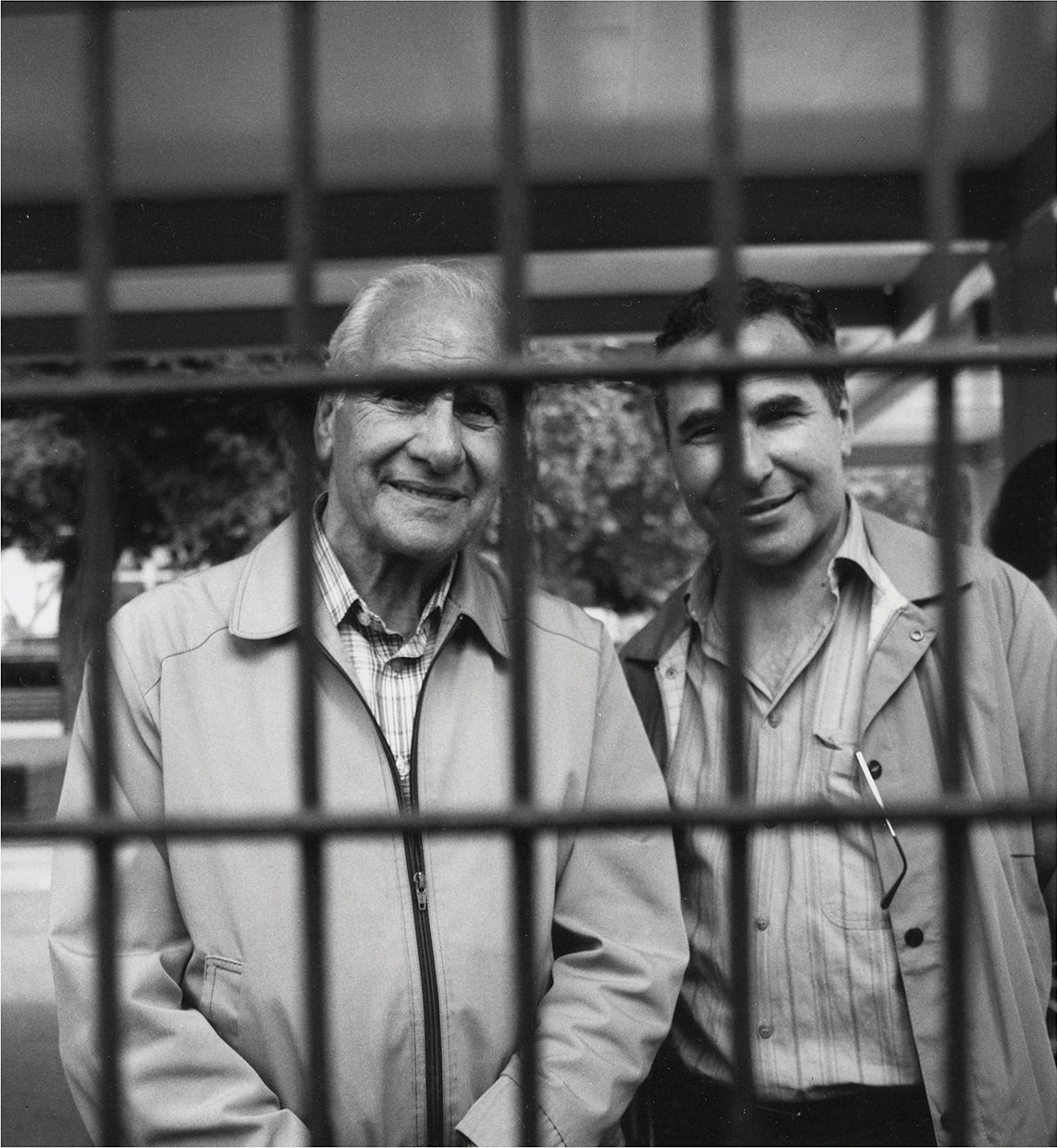

In one other of the essays within the assortment, “A Big Hairy Hand,” Collins offers a wry account of a newspaper stunt at London Zoo involving a digital camera and a gorilla, Salome, wherein the shutter button, disguised in a log and nicely separated from the digital camera itself, is smeared with banana to encourage the large ape to poke it with a stick. Special reward is reserved for a person and his grownup son who, protected on the opposite aspect of the bars, pose willingly and patiently, completely happy to assist in guaranteeing that the animal will get the shot.

Unlike the person and his son who, in strictly metaphorical phrases, meet the gorilla greater than midway, Collins sees Disfarmer’s topics as being altogether with out autonomy. They undergo directions, and in so doing “appear to face us from the netherworld,” quite than from life. Similarly, he regards Arbus’s “fossilised” topics as serving a “cynically malign melodrama” wherein they play their assigned components.

The collaborators: Salome the gorilla’s portrait of two males.

Disfarmer’s studio purchasers recall him as an intimidating presence. He was scary, remembered one man who was photographed by him as a toddler. His topics obeyed him with out query, standing as and the place they had been informed. “Some believe,” says Collins, clearly not believing it, “that Disfarmer’s intimidatory atmosphere was penetrating.” The cause that the gorilla’s {photograph} of the person and his son turned out so nicely, we infer, is that his topics weren’t afraid of him.

“All too often knowingness,” Collins feedback, “is blindness.” He is rather more drawn to photographers who can, by the use of a sort of innocence, reach suggesting a life past the body. As he remarks in passing of the best of all portrait photographers, August Sander, such photographers deal with their topics as “equals.” In distinction to Disfarmer’s “gothic agenda” or Arbus’s forensic method, we’re led in direction of somebody a lot lesser recognized but rather more profitable within the creator’s estimation in nailing the essence of portraiture.

John Alinder, a close to modern of Disfarmer’s, devoted a lot of his time to photographing fellow members of his small neighborhood in rural Sweden within the early a part of the 20th century. His life’s work, represented by 8421 glass negatives, sat unseen in a library basement till it was rediscovered and resurrected to type the premise of an exhibition, held in Landskrona in 2021.

Alinder’s fantastic portraits of his fellow residents will not be, it’s typically acknowledged, significantly subtle in technical phrases. A blur right here, a digital camera tilt there. Yet what inarguably shines by means of is the vitality of the themes, the sense every portrait conveys of a full biography behind the face and the posture, invisible and unknowable to us but substantive all the identical. Collins attributes this high quality to the sympathy the photographer has for the topic. (He says of one other photographer whose work he a lot admires, the Malian Seydou Keïta, that the “heart of his portraits is empathy.”)

Collins acknowledges the memorialising, “melancholic” impact of pictures. “What we can see in the instant of exposure has inexorably passed away.” But a memorial can be an expression of optimism, or on the very least an expression of confidence that there will likely be a future past the second of the picture. One of the numerous issues he admires about Seydou Keïta, as an example, is the best way he “posed his clients so that they were facing diagonally out of the picture…, their faraway look uninhibited by the lens.”

Collins gravitates to these pictures, whether or not of individuals or landscapes, that appear to free their topics quite than to pin them down. Of his personal apply, he writes of returning repeatedly to {photograph} the naked panorama of the Hoo Peninsula in Kent, a topic of which he by no means tires. The attraction lies in the best way that these landscapes “face ahead to open water, where the river meets the sky,” suggesting a counterweight to pictures’s important retrospectivity.

He makes an identical level in a short however transferring meditation on his favorite {photograph}, of a ship mendacity aground and deserted at Brightstone Bay on the Isle of Wight. The topic of the picture has reached the tip of its journey, seeming to rule out the long run. But in a extremely magnified print of the unique contact, Collins can simply spot, within the prime left-hand nook, “a seagull with outstretched wings.”

The Kingsbridge, 1955, photographer unknown.

Collins flirts right here with sentimentality and, as he does elsewhere, with overstatement, one thing he does most clearly when making a case for the need, the place portraits are involved, of a previous relationship between topic and photographer. “The most sensitive portraiture is generally to be found in the family album,” he maintains. In different phrases, when photographer and topic are recognized to 1 one other.

Not solely that, however “it is a delusion to imagine that a photographer can make a genuinely revealing portrait of a complete stranger.” Taken at face worth, so to talk, this appears unlikely, if not merely unfaithful. Whether overstated or not, nonetheless, the central level stays. The pictures that talk to us most successfully and most straight are those that guarantee us of a sympathetic connection between photographer and topic.

In his introduction to Blind Corners, the novelist Will Self factors to its pervasively elegiac high quality. This is partly as a result of loss and remorse are embedded within the materials, in pictures of the irretrievable previous. As Collins places it in his close to to closing paragraph, “photography is inherently melancholic because of our innate sense that what we can see in the instant of exposure has inexorably passed away.”

But that isn’t the one cause. What provides to this elegiac high quality is the truth that the sort of pictures that Collins responds to with such vitality and love is itself retreating into the previous. Photographs which have their roots in issues that occurred, the sort that we are going to more and more see as conventional pictures, at the moment are the uncooked materials for generative fashions, gasoline for the submit photographic world.

This new sort of machine-driven, AI-enabled pictures means a way more tangled relationship with the fact of historic occasions, one which is already giving rise to its personal, very completely different model of melancholy. •

Blind Corners: Essays on Photography

By Michael Collins | Notting Hill | $38.38 | 192 pages

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://insidestory.org.au/moments-of-exposure/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us