This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/walk-via-francigena-thousand-year-pilgrimage-to-rome-italy

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

This article was produced by National Geographic Traveller (UK).

It’s holy week and music is rising from the Chiesa di Santa Maria. First comes the gradual sigh of baroque strings, then a wash of operatic concord as a soprano and alto plunge into the opening traces of Pergolesi’s Stabat Mater. Outside, a blood-orange solar is slipping behind the sage hills surrounding Vetrella, throwing a sq. of daylight onto the church’s frescoed partitions: a honeyed beam that writes life into the eyes of each painted saint and martyr.

I’m coming to the top of my first day on the Via Francigena and already I’m getting a way of the path’s unusual energy — although I’m 12 miles nearer to Rome than I used to be this morning, I seem to have stepped additional again in time. In some ways, it stands to motive. After all, I’ve spent the morning tracing one among Lazio’s historical holloways — the sunken roads etched by the Etruscans someday between 800 and 300 BCE and deepened over the centuries by the footfall of Roman legions, Frankish knights and modern-day pilgrims.

After the live performance, the congregation spills onto the garden, the place I get speaking to blue-eyed Tiziano, who’s travelled from the close by city of Bracciano to be right here. “The springs surrounding this place made it a site of pilgrimage long before the church was built,” he explains, “and yet most people pass it by without even noticing. For me, it’s an overlooked masterpiece.”

The similar may very well be mentioned of the Via Francigena itself — a quiet backroad in comparison with the bustling pilgrim freeway that’s Spain’s Camino de Santiago. The key distinction is that the previous didn’t start life as a pilgrimage path, however relatively advanced into one, its community of roads initially serving as arteries between the Roman Empire and northern territories like Britannia.

The sunken roads etched by the Etruscans someday between 800 and 300 BCE have been deepened over the centuries by the footfall of Roman legions, Frankish knights and modern-day pilgrims. Photograph by Gilda Bruno

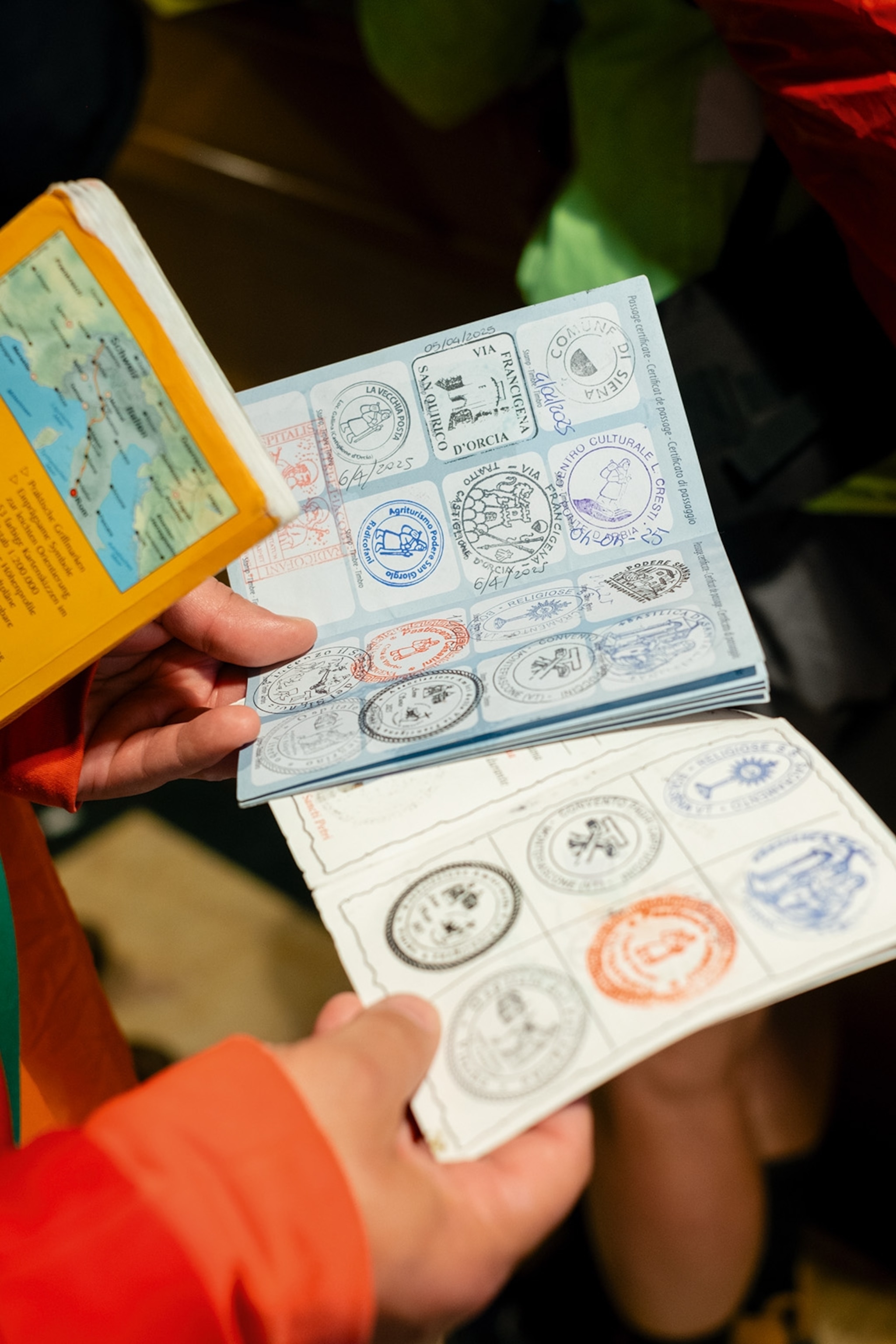

By the Middle Ages, any pellegrino (pilgrim) value their communion wafer may very well be discovered traipsing in the direction of Rome, the place the spirit of St Peter was mentioned to suffuse each root and rock. For the following few days, I’ll be following within the footsteps of 1 such wayfarer: Tenth-century archbishop Sigeric the Serious, little question a infamous celebration animal. In 990 CE, he travelled some 1,200 miles from Canterbury Cathedral to St Peter’s Basilica — by the use of France and Switzerland — to gather his official garment from the Pope. Handily, he documented his return journey, offering a blueprint for right now’s official Via Francigena route. Tackled in full it’s a mammoth 100-day trek, so many pilgrims select to stroll key phases. My personal journey takes within the final 60 or so miles to Rome, a five-day hike by means of cavernous valleys, emerald forests and barely visited hilltop cities. The route is liberating in its simplicity — as long as I make it to my B&B every evening, I ought to attain the Eternal City simply in time for Good Friday.

The wandering monk

Spring is an efficient time to be on the open highway. Lazio is within the midst of an awesome transformation, the area’s cobbled cities brimming with early artichokes, its boulder-strewn woodlands carpeted with anemone and pink cyclamen. Striking out in the direction of the hilltop city of Sutri the next morning, I move a gaunt, olive-wreathed farmhouse. The 12 months’s first swallows glide out and in, their lengthy migration lastly at an finish. It’s right here I meet Brother Ambrose Okema, a Benedictine monk enterprise the Via Francigena by bike. For him, there’s little distinction between we pilgrims and the birds dancing above our heads, for we’re all stirred to wander by the identical invisible drive. “It’s a call from within,” he says, beating a pulse on his chest.

Dressed in Lycra and sat astride a gravel bike, he’s a far cry out of your stereotypical wandering monk: the solitary, staff-bearing pilgrim whose effigy graces each waymark alongside the Via Francigena. His companion Victor Hernandez, a stubbled Puerto Rican, reveals me footage from morning Mass on his cellphone; a priest in Tyrian purple robes utilizing a backyard spray pump to douse the congregation with holy water. “You’ve gotta love Italy,” Victor says, beaming.

The final 60 or so miles to Rome are a five-day hike by means of cavernous valleys, emerald forests and barely visited hilltop cities. Photograph by Gilda Bruno

Tackled in full the Via Francigena is a mammoth 100-day trek, so many pilgrims select to stroll key phases. Photograph by Gilda Bruno

We stroll collectively for a while, descending into the Valle di Tinozza, the place a jade stream guides us previous rockfaces honeycombed with Etruscan tombs. Conversation flows simply on the highway, and shortly Ambrose is recounting his life story: the childhood in war-torn Uganda, his transfer to a monastery in America. I get the sense that this pair’s pilgrimage is as a lot an act of friendship as it’s of religion. “I did the Camino de Santiago solo,” Victor tells me, “so I knew I didn’t want to do this trip alone. After meeting Ambrose at his monastery, it made sense to do it together.”

That night, with 14 miles beneath my belt, I drink a Campari in Sutri’s foremost sq., its baroque fountain trickling sapphire. Beside me, an aged man with thick-framed spectacles is filling his pipe, eyes forged skyward because the rain clouds half. A passing pal berates him for staying out in such situations. “La pioggia lava tutto,” the smoker replies — rain cleans all the pieces. His phrases are nonetheless with me two days later. They echo one thing Sigeric and his fellow medieval pilgrims should even have felt to be true — that in enduring the weather they have been one way or the other cleaning themselves. Call it purification by struggling.

From their howls of laughter, it’s clear English pilgrims Maris Waterhouse and Sarah Thompson haven’t any intention of struggling their option to Rome. “We’re not religious at all,” Maris tells me as we fall into step getting into Insugherata Natural Reserve, a 1,800-acre patchwork of forest and farmland bordering Rome. “Most of our lives are spent in the same routine — but this is something different.” With comically good timing, at that second, a really giant, very furry wild boar emerges from the forest. I fleetingly marvel if he’s right here to enact revenge for final evening’s dinner, pappardelle pasta served with ragù di cinghiale, however he merely raises his snout, sniffs the air and trots off.

Our pal’s habitat slowly recedes, giving option to glimmering shopfronts and warm-lit cafes — each desk adorned with some limp-limbed pilgrim unable to maneuver one other inch. Their reluctance is comprehensible, because the Via Francigena has yet another problem in retailer: Monte Mario, Rome’s tallest hill.

Praying for divine intervention, I crawl up its cobbled again; previous silvery olives and flat-topped pines swaying within the afternoon breeze. I spot two peregrine falcons circling overhead, after which, fairly with out warning, catch sight of one thing I’d practically forgotten: St Peter’s Basilica, its gilded dome a second solar above the town’s sweep of historical spires.

The remaining strategy is sort of a dream, baroque avenues heavy with orange blossom giving option to the Renaissance splendour of St Peter’s Square. Photograph by Gilda Bruno

The remaining strategy is sort of a dream, baroque avenues heavy with orange blossom giving option to the Renaissance splendour of St Peter’s Square. At this level, Sigeric would doubtless have commenced the compulsory circuit of Rome’s different holy locations — a pilgrimage inside a pilgrimage.

But after a number of moments of gazing on the basilica’s gold-encrusted inside, Sarah’s earlier phrases begin ringing in my ears like a command: “All I want from a trip like this is a long walk and a good meal at the end of it.” Within the hour I’m sat exterior La Quercia, an osteria in Monteforte, stretching my legs beneath a desk set with a bowl of smoky, parmesan-dusted pasta amatriciana. Dinner and a well-deserved relaxation. Some pleasures really are everlasting.

To subscribe to National Geographic Traveller (UK) journal click on here. (Available in choose nations solely).

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.nationalgeographic.com/travel/article/walk-via-francigena-thousand-year-pilgrimage-to-rome-italy

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us