This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theguardian.com/food/2025/aug/26/really-rich-physics-going-on-the-science-behind-a-flat-pint-of-lager

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us

A flat pint of beer with no head is a typical gripe amongst pub-goers. And whereas the bar workers’s pint-pulling approach is usually assumed to be the trigger, scientists have found that the soundness of beer foam can also be extremely depending on the chemical make-up of the brew.

Triple fermented beers have probably the most steady foams, the examine discovered, whereas the froth created by single fermentation beers, together with lagers, are inherently extra prone to collapse earlier than you could have time to take the primary sip.

“We now know the mechanism exactly and are able to help the brewery improve the foam of their beers,” mentioned Prof Jan Vermant, a chemical engineer at ETH Zurich, who led the examine.

The analysis started as a “typical Friday afternoon project”, Vermant mentioned. “We decided to study beer and found this really rich physics going on.”

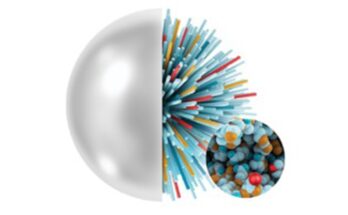

Like another foam, beer foam is fabricated from many small bubbles of air, separated from one another by skinny movies of liquid. Under the pull of gravity and the strain exerted by surrounding bubbles, the movies of liquid slowly skinny out, the bubbles pop and the froth collapses. But the speed at which this course of happens was discovered to differ relying on the type of a barley-derived protein, known as Liquid Transfer Protein 1 (LTP1).

“The idea was to directly study what happens in the thin film that separates two neighbouring bubbles,” mentioned Dr Emmanouil Chatzigiannakis, an assistant professor at Eindhoven University of Technology and first writer of the examine.

Turning to a set of scientific imaging methods, the crew was in a position to decide how these skinny movies might maintain collectively to make a steady foam.

“We can directly visualise what’s happening when two bubbles come into close proximity,” Chatzigiannakis mentioned. “We can directly see the bubble’s protein aggregates, their interface and their structure.”

In single fermentation beers, the LPT1 proteins have a globular type and prepare themselves densely as small, spherical particles on the floor of the bubbles. “It’s not a very stable foam,” Vermant mentioned.

During the second fermentation, the proteins develop into barely unravelled and type a net-like construction that acts as a stretchy elastic pores and skin on the floor of bubbles. This makes the liquid extra viscous and the bubbles extra steady.

During the third fermentation, the LPT1 proteins develop into damaged down into fragments which have a water-repellent (hydrophobic) finish and a “water-loving” (hydrophilic) finish. In these beers, a phenomenon known as the Marangoni impact comes into play, which drives liquid circulate from protein-rich (thicker) areas of the bubble to protein-depleted (thinner) areas, delaying the bursting of bubbles. The same impact is seen with cleaning soap bubbles, the place swirling can typically be seen on the floor for a similar cause.

“These protein fragments function like surfactants, which stabilise foams in many everyday applications such as detergents,” Vermant mentioned. Some of the triple fermented beers had foams that have been steady for quarter-hour.

Vermant, who’s Belgian, mentioned the findings might assist brewers improve or lower the quantity of froth as desired. There could also be differing views, although, on whether or not a foamy pint is fascinating or represents poor worth for cash. “Foam isn’t that important everywhere beer is served – it’s basically a cultural thing,” he mentioned.

The findings are printed within the journal Physics of Fluids.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theguardian.com/food/2025/aug/26/really-rich-physics-going-on-the-science-behind-a-flat-pint-of-lager

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us