This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://lithub.com/how-photographer-frank-s-matsura-challenged-white-americas-hegemonic-view-of-the-west/

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us

This story is well-worn native lore, but nonetheless little identified past the territories of present-day north-central Washington State. But the story bears significance nicely past the remoteness and seeming inconsequence of its place: as an extended overdue contribution to the historical past of images, definitely, and no less than equally for what it illuminates in regards to the historical past of US settler colonialism on the micro-level of its regional transformations and interpersonal relations.

Indeed, the area’s uneven, overlapping histories resonate with that bigger settler colonial narrative, which stays conspicuous in its geography: comprised of the Colville Indian Reservation and its twelve confederated tribes; the southern ancestral lands of the Syilx Okanagan Nation; and the settler cities of Okanogan, Omak, Conconully, and dozens of others—all a part of the world of the Indigenous (Columbia) Plateau and the Native peoples who’ve lived on its lands and cared for them since time immemorial. Immersed on this historical past, this story begins with the arrival of a stranger thirty years after the pressured institution of the Colville reservation in 1872.

Untitled, Frank Matsura {photograph}, ca. 1903–1913. A staged scene of a Native American man with feathers in his hatband and blanket wrapped round his waist utilizing a rifle to cease a card recreation amongst six males; Matsura is on the far proper.

Untitled, Frank Matsura {photograph}, ca. 1903–1913. A staged scene of a Native American man with feathers in his hatband and blanket wrapped round his waist utilizing a rifle to cease a card recreation amongst six males; Matsura is on the far proper.

In 1903, a Japanese immigrant named Frank Sakae Matsura moved from Seattle to Conconully, then to newly constructed Okanogan, from a cosmopolitan metropolis steadily rising as a serious commerce and transport heart to what would have appeared to most metropolis dwellers as the center of nowhere. A good-looking, impish extrovert, good previous Frank rapidly befriended seemingly everybody within the native communities. He additionally hauled fairly of little bit of photographic {hardware} to this obvious middle-of-nowhere; arrange a images studio and reward store; and, as a beloved resident, proceeded to take hundreds of pictures of its individuals, locations, and occasions till his premature, sudden dying brought on by tuberculosis in 1913.

Matsura’s pictures have been prized by the locals to whom he bought and gifted his work, and so they gained restricted recognition and circulation past: journal illustrations used to entice potential homesteaders again east; celebrated submissions to the 1909 Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition in Seattle; scenes of business and agriculture utilized in a 1911 Great Northern Railway promoting marketing campaign; and the hundreds of postcards despatched by locals to household, pals, and others elsewhere.

After Matsura’s dying, a considerable assortment of his pictures, bequeathed to his good friend Judge William Compton Brown, was donated as a part of Brown’s property to the Washington State University archives. However, hundreds of fragile gelatin dry glass plates on which his pictures have been recorded remained saved in a storage in Okanogan, undiscovered till the mid-Seventies; the late historian JoAnn Roe chosen and launched some 140 of those pictures in a sublime, small-press e book, Frank Matsura: Frontier Photographer, that was revealed in 1981.

Although it quickly went out of print, the quantity garnered sporadic consideration for Matsura’s work over the subsequent three a long time. Since the 2010s, nonetheless, his pictures have began to look with larger frequency and impression in small exhibitions all through the Pacific Northwest, incomes Matsura an ever-widening circle of admiration and appreciation.

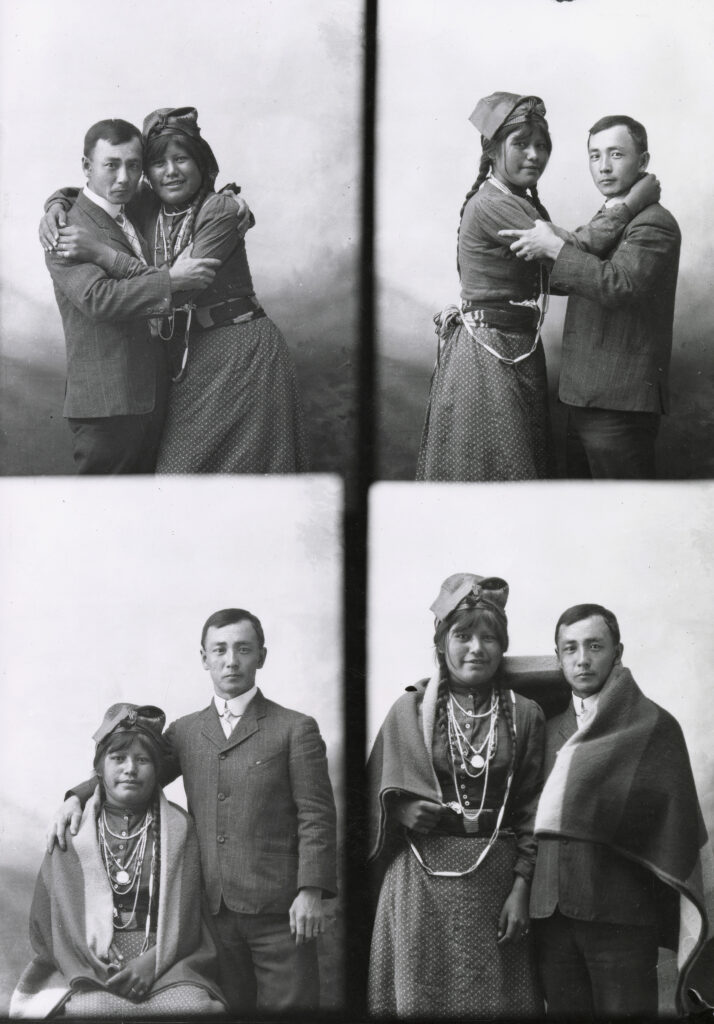

Untitled, Frank Matsura {photograph}, ca. 1910. Matsura, Cecil Jim, and younger males pose for portraits at Matsura’s studio.

Untitled, Frank Matsura {photograph}, ca. 1910. Matsura, Cecil Jim, and younger males pose for portraits at Matsura’s studio.

Over the span of a close to decade from 1903 to 1913, with unflagging enthusiasm and dedication, Matsura visited seemingly everybody and all over the place along with his “magic box” and tripod in hand—typically with no less than two, since a number of pictures painting Matsura posing with one in all his cherished cameras. Hence, his photographic archive supplies a complete visible document of the area’s colonial settlement: infrastructural improvement together with the founding of his adopted hometown, Okanogan, development of Conconully Dam, set up of electrical energy and waterworks, planting of orchards, extension of the railroads, and arrival of cars. And he produced portraits—severe and playful, formal and informal—of Native peoples and settlers alike, adapting to the modernization of the Indigenous Plateau.

Matsura didn’t impose any specific interpretive body onto his topics and positively not a dominant cultural perception or perspective with which he might or might not have been acquainted.

The most exceptional high quality of this physique of labor, nonetheless, is the way through which it unsettles and departs from the views and conventions of canonical American West images and studio portraiture. This radical distinction is most evident in his portraits of the area’s Native peoples, which artwork historian ShiPu Wang felicitously characterizes as “imagery of the Other by the Other”: a counter archive of American Indian illustration produced by an eccentric, educated Japanese immigrant, whose motives for relocating to Okanogan stay undetermined.

The canonical work of Edward Curtis established the tragic view and elegiac rhetoric of Native individuals as noble savages unassimilable to Progress and therefore destined for cultural, if not organic, extinction. Even the previous work of distinguished white male photographers like William Henry Jackson and Lee Moorhouse participated on this romanticizing mission. Jackson, celebrated for his iconic landscapes of “untouched” Western landmarks, documented the tribes that his Union Pacific and US Geological Survey expeditions encountered not for themselves, however as options of the unincorporated territories to be remodeled by the inexorable pressure of westward enlargement. Moorhouse, like Matsura and in contrast to Curtis or Jackson, was a resident of the Pacific Northwest (and moreover a federal Indian agent) who had long-standing relationships with the tribes of the Umatilla Indian Reservation.

Yet he, too, adopted and produced a romanticizing view of his Indian topics: like Curtis, Moorhouse staged his portraits to raised conform to his perfect of melancholic authenticity, costuming Indians with clothes and artifacts from his intensive Native wardrobe and posing them stoically, to exemplify the Indian lifestyle that he believed would disappear as a fatalistic corollary of Manifest Destiny.

Arguably, the one picture most liable for codifying this trope is Edward Curtis’s 1904 masterpiece, The Vanishing Race: a bunch of Navajo on horseback slowly driving into the perspectival distance of the {photograph}—vanishing, metaphorically, into the previous. The picture was so vivid and memorable that it seems to have served because the template for the closing passage of Zane Grey’s common, if controversial, 1925 novel, The Vanishing American: in opposition to a “magnificent, far-flung sunset…the Indians were riding away.” Grey continues: “It was an austere and sad pageant….Far to the fore the dark forms, silhouetted against the pure gold of the horizon, began to vanish, as if indeed they had ridden into that beautiful prophetic sky….At last only one Indian was left on the darkening horizon—the solitary Shoie—bent in his saddle, a melancholy figure, unreal and strange against that dying sunset—moving on, diminishing, fading, vanishing—vanishing.”

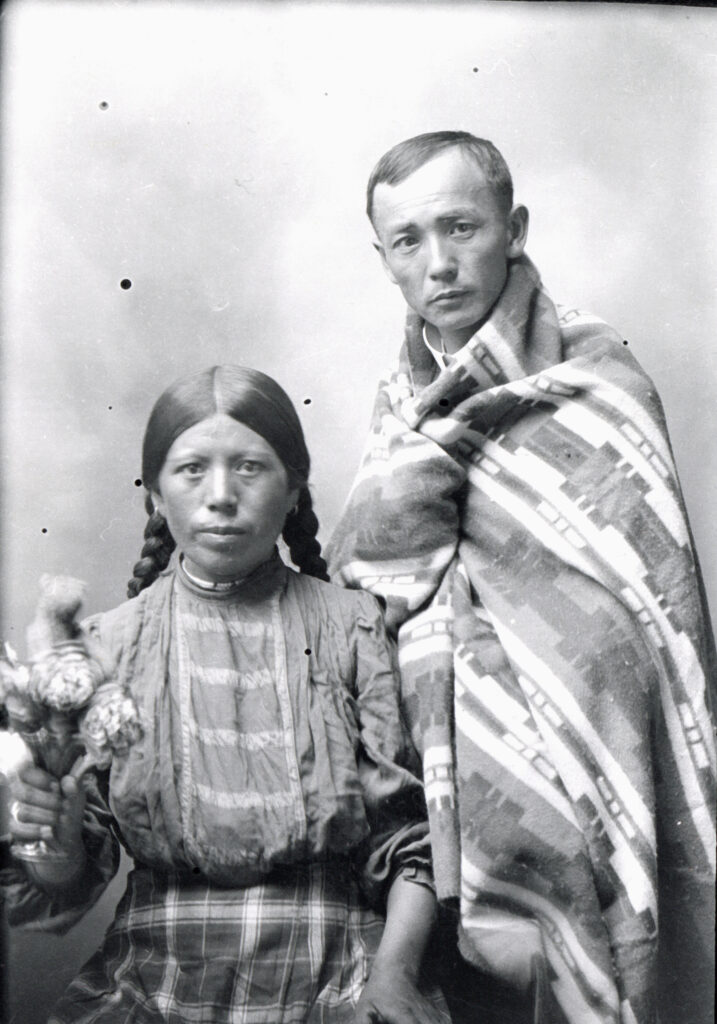

Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio, ca. 1912. Matsura and Susan Timento pose for an image in his studio in Okanogan. Matsura stands with a blanket wrapped round his shoulders. Timento sits in a chair beside him, holding a teddy bear. She is the aunt of Cecil Jim.

Matsura and Susan Timento Pose at Studio, ca. 1912. Matsura and Susan Timento pose for an image in his studio in Okanogan. Matsura stands with a blanket wrapped round his shoulders. Timento sits in a chair beside him, holding a teddy bear. She is the aunt of Cecil Jim.

To ensure, Grey’s novel is a literary protest in opposition to the mistreatment of American Indians by the federal authorities and Christian missionaries, and his authentic denouement is a bit more difficult. In it, Nophaie, the novel’s Indian male protagonist, and Marian, his white feminine companion, plan to marry and reside on the reservation as they watch the survivors of Nophaie’s tribe “vanishing” into the sundown. The press, nonetheless—fearing backlash to its optimistic depiction of interracial romance—rewrote the conclusion with out Grey’s information or consent, killing off Nophaie and the offending prospect of miscegenation. Grey’s son, Loren Grey, restored his father’s authentic ending within the novel’s 1982 Pocket Books reprint, however the vanishing mythos stays intact, with the final of the tribe wistfully following Curtis’s Navajo into the temporal graveyard of the previous.

Matsura’s pictures stand in sharp distinction to this highly effective, prevailing fable. Unlike his extra prestigious white male counterparts, Matsura didn’t impose any specific interpretive body onto his topics and positively not a dominant cultural perception or perspective with which he might or might not have been acquainted. (And if he knew about it via studying or his visits to Seattle, evidently he didn’t purchase it.) Instead, his pictures are distinguished by, as Colville tribal artist and curator Michael Holloman places it, “conceptually sophisticated and collaborative portraits of individuals and families with whom Matsura maintained trusting relationships.” He didn’t ventriloquize via his topics; he enabled all of them, settlers and Natives alike, to current themselves to themselves and others, on their very own phrases. Hence, opposite to the melancholic archive of vanishing Indians inexorably dying off to make manner for settler colonial modernity, Matsura’s work as an alternative illuminates what Anishinaabe author Gerald Vizenor calls “survivance”: “renunciations of dominance, tragedy and victimry” and the “active sense of presence, the continuance of native stories, not a mere reaction, or a survivable name.”

This “active sense of presence” is seen and felt in Matsura’s just-visiting portrait of his good friend Chiliwhist Jim, Methow drugs man: we don’t know why he’s on the town, however he rides and carries himself with function. Front and heart body, Chiliwhist Jim presides over the scene, and the digicam, whereas the white males and their canine sit or stand idly, receding into the perspectival distance behind him. Ironically, though this {photograph} in itself doesn’t reveal it, the clock is damaged with its arms ceaselessly frozen at 8:17, the identical time because it seems in different pictures. In any occasion, Chiliwhist Jim has enterprise to take care of and isn’t right here to attend for his extinction or journey off into the previous.

Matsura and Miss Cecil Chiliwhist, ca. 1910.

Matsura and Miss Cecil Chiliwhist, ca. 1910.

More broadly, what sorts of tales of survivance do these pictures allow, help, and proceed? At the Northwest Museum of Arts and Culture in Spokane, Washington, at a panel occasion commemorating its extraordinary exhibition of Matsura’s pictures, curator Holloman intriguingly remarked that “Frank was a coyote.” Of course, shape-shifting Coyote ranks among the many most commemorated Animal People all through Indian nation, who “amused himself by getting into mischief and stirring up trouble,” based on Mourning Dove, esteemed Okanogan and Colville author of the Twenties and Thirties.

Further, Coyote “delighted in mocking and imitating others, or in trying to, and, as he was a great one to play tricks, sometimes he is spoken of as ‘Trick Person.’” This is to not recommend that Matsura was Coyote personified; quite, that Matsura’s persona and perspective manifested trickster qualities inscribed in and expressed via his images. Contrary to his canonical white counterparts, who handed off their fictionalizing show of Indians as genuine and true, Matsura’s pictures typically mirthfully reveal their ruse—like Belgian surrealist René Magritte’s 1929 portray The Treachery of Images, baldly divulging, “This is not a pipe.” Take, for instance, an outside scene that the Okanogan County Historical Society captions thus: “A staged scene of a Native American man with feathers in hat band and blanket using a rifle to stop a card game among six men on a blanket.”

Whose concept was this, and what sorts of settler-colonial relations does this mock holdup invert? The joke is clear within the {photograph} itself. Presumably, everyone seems to be in on it; however who’s the joke on, and for whom? The solutions might nicely rely not solely on whether or not we ask these questions in 1910 or at the moment however on which aspect of the Okanogan River—settler cities or Colville reservation—we pose them. Likewise, replicate on a collection of twelve portraits through which three younger white males, Matsura, and his good friend Cecil Jim (niece of the imposing Chiliwhist Jim) assume completely different pairings and playfully swap hats.

What can we make of this cross-racial chumminess between the sexes in 1910 Okanogan, on the settler aspect of the river? In pictures taken outdoors the studio, we see no such informal sociability, and positively not flirtiness, throughout race and intercourse and maybe class, as nicely. Indeed, Matsura’s work, as Colville (Entiat) engineer and author Wendell George says of Coyote, “made you realize that things were not always the way they seemed to be.” Throughout his archive of Coyote images, colonial settlement of the Indigenous Plateau—landscapes—and the destiny of its first peoples—portraiture—are usually not what they, within the canonical document, appear to be.

__________________________________

From Frank S. Matsura: Iconoclast Photographer of the American West, edited by Michael Holloman. Copyright © 2025. Available from Chronicle Books.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://lithub.com/how-photographer-frank-s-matsura-challenged-white-americas-hegemonic-view-of-the-west/

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us