This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://scitechdaily.com/johns-hopkins-unlocks-new-chemistry-for-faster-smaller-microchips/

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us

Scientists at Johns Hopkins have uncovered a brand new technique to construct microchips so small they’re almost invisible.

By combining metals and light-sensitive chemistry, they’ve pioneered a way that might make chips sooner, cheaper, and much more highly effective. This leap in microchip design might reshape every little thing from smartphones to airplanes, opening a path to the subsequent period of know-how.

Breakthrough in Microchip Innovation

Researchers at Johns Hopkins have recognized new supplies and developed a brand new method that might speed up the race to provide microchips which might be smaller, sooner, and extra inexpensive. These chips energy almost each nook of recent life, from smartphones and family home equipment to cars and plane.

The scientists demonstrated the best way to construct circuits so tiny they can’t be seen with the human eye, utilizing a way designed to be each extremely correct and cost-effective for large-scale manufacturing.

The outcomes of this analysis had been printed just lately in Nature Chemical Engineering.

Overcoming Manufacturing Barriers

“Companies have their roadmaps of where they want to be in 10 to 20 years and beyond,” stated Michael Tsapatsis, a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of chemical and biomolecular engineering at Johns Hopkins University. “One hurdle has been finding a process for making smaller features in a production line where you irradiate materials quickly and with absolute precision to make the process economical.”

According to Tsapatsis, the superior lasers required to etch patterns at these extraordinarily small scales are already out there. The lacking piece has been the best supplies and strategies that may maintain tempo with the demand for ever smaller microchips.

How Microchips Are Made

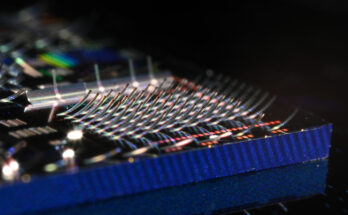

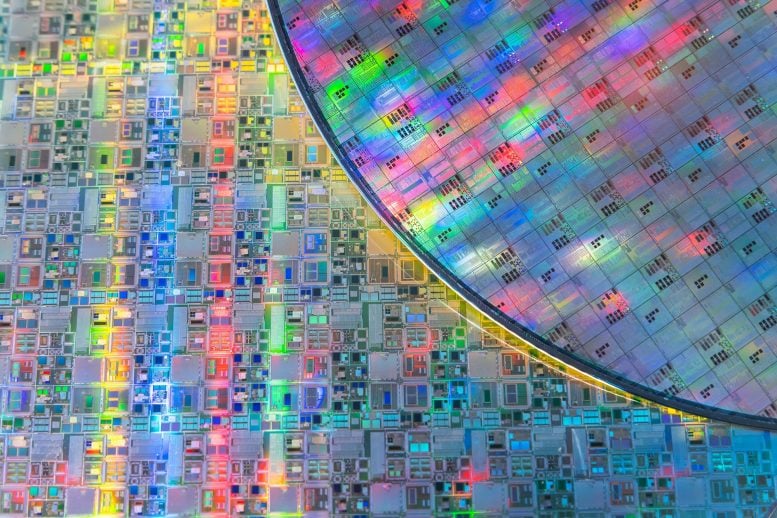

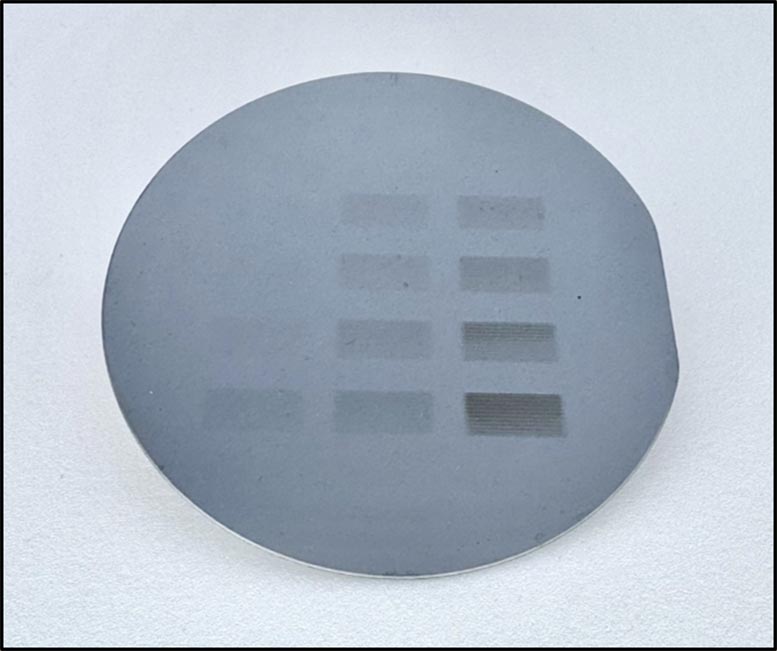

Microchips are flat items of silicon with imprinted circuitry that execute fundamental features. During manufacturing, producers coat silicon wafers with a radiation-sensitive materials to create a really high quality coating referred to as a “resist.” When a beam of radiation is pointed on the resist, it sparks a chemical response that burns particulars into the wafer, drawing patterns and circuitry.

However, the higher-powered radiation beams which might be wanted to carve out ever-smaller particulars on chips don’t work together strongly sufficient with conventional resists.

Pushing Past Current Limits

Previously, researchers from Tsapatsis’s lab and the Fairbrother Research Group at Johns Hopkins discovered that resists fabricated from a brand new class of metal-organics can accommodate that higher-powered radiation course of, referred to as “beyond extreme ultraviolet radiation” (B-EUV), which has the potential to make particulars smaller than the present commonplace measurement of 10 nanometers. Metals like zinc soak up the B-EUV mild and generate electrons that trigger chemical transformations wanted to imprint circuit patterns on an natural materials referred to as imidazole.

This analysis marks one of many first occasions scientists have been in a position to deposit these imidazole-based metal-organic resists from answer at silicon-wafer scale, controlling their thickness with nanometer precision. To develop the chemistry wanted to coat the silicon wafer with the metal-organic supplies, the group mixed experiments and fashions from Johns Hopkins University, East China University of Science and Technology, École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Soochow University, Brookhaven National Laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The new methodology, which they name chemical liquid deposition (CLD), may be exactly engineered and lets researchers rapidly discover varied mixtures of metals and imidazoles.

“By playing with the two components (metal and imidazole), you can change the efficiency of absorbing the light and the chemistry of the following reactions. And that opens us up to creating new metal-organic pairings,” Tsapatsis stated. “The exciting thing is there are at least 10 different metals that can be used for this chemistry, and hundreds of organics.”

Looking Ahead to Next-Gen Manufacturing

The researchers have began experimenting with completely different mixtures to create pairings particularly for B-EUV radiation, which they are saying will probably be utilized in manufacturing within the subsequent 10 years.

“Because different wavelengths have different interactions with different elements, a metal that is a loser in one wavelength can be a winner with the other,” Tsapatsis stated. “Zinc is not very good for extreme ultraviolet radiation, but it’s one of the best for the B-EUV.”

Reference: “Spin-on deposition of amorphous zeolitic imidazolate framework films for lithography applications” by Yurun Miao, Shunyi Zheng, Kayley E. Waltz, Mueed Ahmad, Xinpei Zhou, Yegui Zhou, Heting Wang, J. Anibal Boscoboinik, Qi Liu, Kumar Varoon Agrawal, Oleg Kostko, Liwei Zhuang and Michael Tsapatsis, 11 September 2025, Nature Chemical Engineering.

DOI: 10.1038/s44286-025-00273-z

Authors embody Yurun Miao, Kayley Waltz, and Xinpei Zhou from Johns Hopkins University; Liwei Zhuang, Shunyi Zheng, Yegui Zhou, and Heting Wang from East China University of Science and Technology; Mueed Ahmad and J. Anibal Boscoboinik from Brookhaven National Laboratory; Qi Liu from Soochow University; Kumar Varoon Agrawal from École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne; and Oleg Kostko from Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Never miss a breakthrough: Join the SciTechDaily publication.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://scitechdaily.com/johns-hopkins-unlocks-new-chemistry-for-faster-smaller-microchips/

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us