This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-we-alone-nasas-habitable-worlds-observatory-aims-to-find-out/

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us

It’s a sweltering Tuesday in Washington, D.C., the type of day that stretches the definition of Earth as a “habitable” planet. But on an eighth-floor terrace close to the U.S. Capitol constructing, dozens of individuals are exterior anyway, speaking and watching as passersby dart between swimming pools of shade on the sticky streets beneath. Besides the warmth, the onlookers are sweating one thing else, too—an audacious venture to be taught, eventually, whether or not we now have any neighbors residing on Earth-like planets in our neck of the Milky Way.

Back inside, a boisterous reception is underway. Hundreds of scientists and engineers, NASA leaders, lobbyists, congressional staffers and Senator Mark Kelly of Arizona are additionally discussing the seek for ET.

Surveilling alien worlds for indicators of life is much more than a twinkle on this neighborhood’s eye. It’s the explanation why everyone seems to be right here for a four-day science conference in late July, on the top of D.C.’s arguably liveable oppressive summer time warmth. They are prepping for NASA’s subsequent flagship house telescope, a multibillion-dollar machine that would launch as early because the mid-late 2030s and reveal whether or not Earths are as common as sand on a seaside or if our watery world is as a substitute a lonely island in a quiet sea. Called the Habitable Worlds Observatory, the telescope’s core mission is to seek for indicators of alien biospheres on Earth-size planets orbiting sunlike stars—worlds, a minimum of in concept, that might be twins of our personal.

On supporting science journalism

If you are having fun with this text, contemplate supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By buying a subscription you might be serving to to make sure the way forward for impactful tales concerning the discoveries and concepts shaping our world right this moment.

This search calls for one thing conceptually easy however breathtakingly troublesome: we have to truly see these faraway planets. To try this, the telescope should separate every world’s nearly impossibly faint gleam from the overwhelming glare of its star.

“HabWorlds is not out to answer your typical science question,” mentioned astrophysicist Chris Stark of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center (GSFC), utilizing what’s turn into the popular nickname for the mission, throughout a presentation the day earlier than. “It is arguably attempting to answer the single most profound unanswered question in the history of science and in the history of humankind.”

As Stark spoke, “Are we alone?”—in big letters—loomed over the viewers from certainly one of his slides, nearly daring anybody to disclaim the query’s significance. Absent any reply, it’s completely affordable to assume that our planet is, and that we’re, both as frequent as dust or astronomically implausible sufficient to symbolize life’s sole spark all through the complete observable universe.

The fact might properly lie between these immense extremes, and HabWorlds’ deliberate seek for life in a number of star methods might be our greatest method to discover out—if the observatory ever will get off the bottom. As laborious as the issue of discovering ET could also be, overcoming the numerous terrestrial obstacles on HabWorlds’ path to the launchpad might but show tougher. Some of these obstacles are technical, akin to selecting the best targets to analyze and growing modern however inexpensive devices to get the job accomplished.

Others are extra grossly mundane and political. During the assembly and within the weeks afterward, energy brokers within the White House and Congress had been hashing out finances plans that would devastate federally funded U.S. science. For NASA, these plans would decrease the curtain on dozens of its iconic house missions and make it very troublesome (if not not possible) to launch new ones. But house science is only one small sew within the material of life for many Americans, and its potential destroy pales in opposition to this nation’s rising tide of socioeconomic disruption, civil unrest and political violence. So for HabWorlds, one other, extra urgent query looms: Can a nation so busy ripping itself aside come collectively to attain any massive, daring aspiration—particularly one as lofty as fixing life’s cosmic thriller?

To the conference-goers, this second was all of the extra motive to spend just a few enlightened, unflinching days immersed within the challenges and alternatives of their chosen activity. “We needed to be reminded that we have the power to create a world we want to see,” mentioned Janice Lee, an astronomer on the Space Telescope Science Institute and one of many assembly organizers, to Scientific American afterward.

Astrobiology’s Apollo Moment

In the late Nineties, Shawn Domagal-Goldman was dwelling in Chicago, on break from school. Normally, metropolis lights—and stray moonlight—made it troublesome to see the twinkling tapestry overhead. This evening was completely different as a result of a complete lunar eclipse introduced deeper darkness to the sky. With the moon in Earth’s shadow, Domagal-Goldman and his youthful brother discovered themselves on their entrance garden, gazing up on the stars.

“Do you think there’s anyone out there?” his brother requested. “I remember freezing for a solid couple of minutes,” Domagal-Goldman recollects. “And I was like, ‘I don’t know, man. That’s a really tough question, but it seems like one worth thinking about.’”

Fast-forward greater than a quarter-century, and Domagal-Goldman is now an astrobiologist in command of NASA’s complete astrophysics division, nonetheless transfixed by the abiding thriller of our obvious solitude. It’s his job to handle and oversee NASA’s astrophysics fleet, together with such flagship missions because the venerable (and beloved) Hubble Space Telescope, the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope. Each of those initiatives has a particular place in his coronary heart, however the Habitable Worlds Observatory will get him significantly excited.

“I cannot hide my passion for this mission,” he admits. “In any field, there aren’t many opportunities where you get to be a part of something that can literally change the world—and that’s not hyperbole. For many people who work on this, including myself, we view this as an Apollo-like moment. I think about those pictures of Earth from the moon and what it meant to see ourselves that way, and I think this is a similar chance to change our view.”

NASA’s present nice observatories—like Hubble, JWST and their siblings—have helped us to learn our cosmic origin story, revealing how the massive bang’s blaze of vitality infused the new child universe with the physics wanted to forge atoms, stars, galaxies, planets and ultimately life. The Habitable Worlds Observatory might inform us how usually that story unfolds past Earth.

“My expectation is that there is life out there, and the question is: How frequent is it? It could be very rare. It could be very common,” says Evgenya Shkolnik of Arizona State University, an astrophysicist and co-chair of HabWorlds’ Community Science and Instrument Team. “I have no idea. But one thing in astronomy we’ve never done is discover just one of something.”

In its seek for extraterrestrial life, HabWorlds will goal exo-Earths—rocky worlds in temperate orbits round sunlike stars—inside about 100 light-years of the photo voltaic system. One of the mission’s major duties will likely be to seek out just a few dozen of these worlds which are ripe for in-depth examine. But sunlike stars will be 10 billion instances brighter than any orbiting exo-Earth can be. To discover these dusky worlds, the telescope will make use of a starlight-blocking instrument referred to as a coronagraph; as soon as the star is masked, the sunshine from an orbiting Earth-size planet will be seen.

The observatory will then examine the composition of the planet’s ambiance in infrared and ultraviolet mild. As the telescope dissects these nearly inscrutably faint planetary gleams, it would search for the spectral signatures of molecules that, right here on Earth, are intimately related to life. Short of receiving an interstellar radio transmission, discovering wriggling Martian microbes or Europan cephalopods or watching a starship contact down subsequent to the U.S. Capitol, a HabWorlds detection of gases akin to oxygen, ozone and methane within the skies of a heat, moist, rocky planet can be the perfect proof for alien life we might get.

Biology’s atmospheric fingerprints are after all nonetheless considerably of an open query on alien worlds, however the knowledge harvested by HabWorlds ought to a minimum of give scientists one thing to debate. “We know what we’re looking for with respect to the signatures of life that we can already identify on a living planet, such as our own,” Shkolnik says.

But that’s not all HabWorlds will likely be doing. As it sniffs for whiffs of alien biospheres, the observatory can even carry out transformative research of the distant universe and of objects in our personal photo voltaic system. Its uniquely highly effective optics will assist astronomers be taught extra about darkish matter and darkish vitality, the evolution of galaxies, the lives and deaths of stars, our solar’s wealthy retinue of planets and moons, and even probably Earth-threatening comets and asteroids. Such capabilities are essential for getting broader buy-in from the complete astronomical neighborhood, not all of whom see a seek for aliens as their guiding star. (Technically, a lot of that buy-in already occurred years in the past, when a once-every-10-year Decadal Survey of the U.S. house science neighborhood anointed HabWorlds because the nation’s highest new precedence in astrophysics.)

“This is the strongest science case of any flagship I’ve ever been a part of, whether I’ve helped build it, fix it or review it,” says Lee Feinberg, HabWorlds’ principal architect and an engineer at GSFC. “That gets me really excited.”

The Need for Speed

In March 1930, nearly instantly after the inventory market crash that rang within the Great Depression, crews started constructing a hulking skyscraper on Manhattan, N.Y.’s Fifth Avenue. Each week, these employees added greater than 4 flooring to the rising construction of glass, concrete and metal till it soared to be superlative: this was the world’s tallest constructing, the primary to prime 100 tales.

On May 1, 1931, U.S. president Herbert Hoover turned on the skyscraper’s lights.

A mere 21 months had elapsed since architects drew up the primary plans for what’s now referred to as the Empire State Building—an artwork deco edifice that dramatically modified New York City’s skyline and, in some ways, Americans’ conceptions about what we as a nation might obtain.

For Feinberg, a veteran of a number of flagship house telescopes, that story is much less of a parable and extra of a blueprint. It demonstrates, he says, that with cautious planning and concerted motion, we are able to obtain nice issues in nearly no time in any respect—nice issues akin to constructing the primary house telescope to seek out alien biospheres.

“If we could match their level of planning and thought, I think this could be done a lot faster and for a lot less money. But we also need to solve hard technical problems,” Feinberg says. “That’s what we’re trying to do with HabWorlds—maybe not in a year, although that would be amazing.”

Impatience will not be the principle motive to maneuver rapidly; the perfect motive to go quick is that pace can get monetary savings. (Delays in the course of the growth of JWST value NASA greater than $1 million a day.)

“It’s all about doing it less expensively, and the way you do that is to do it fast,” Feinberg says.

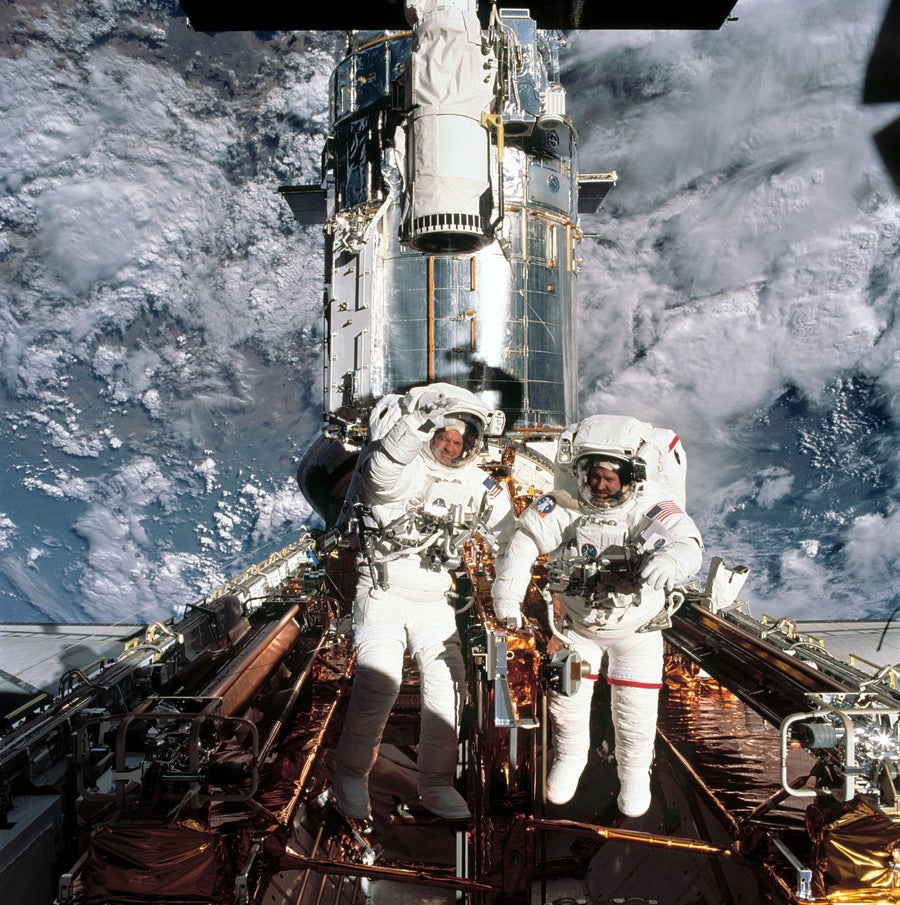

One of the secrets and techniques to hurry, Feinberg and his colleagues argue, will be discovered within the Hubble Space Telescope. Launched in 1990, Hubble was designed to be serviceable, with devices that might be swapped out and tinkered with by human palms. Between 1993 and 2009, astronauts visited Hubble 5 instances to restore, improve or substitute elements, every time tremendously bettering the telescope and lengthening its life. Had Hubble’s planners as a substitute waited for know-how to meet up with all their aspirations, the observatory may by no means have launched within the first place.

“When we sent up Hubble, it was not a great observatory. It was an okay observatory,” says John Grunsfeld, a veteran astronaut, former NASA science chief and self-proclaimed Hubble hugger, who flew on three of these servicing missions. Grunsfeld is now working to make sure that the observatory can be serviced—albeit robotically as a result of the telescope will function from the identical location as JWST, a blissfully darkish deep-space spot 1.5 million kilometers away referred to as the Earth-sun Lagrange Point 2, or L2.

“As much as I love human spaceflight, Earth-sun L2 is not a fun place to go. Orbiting the earth is amazing. Going to Mars would be amazing. Going to the moon would be cool. Going to L2 is like two months of travel to spend a few days at a telescope and two months back in a really hazardous place,” Grunsfeld says. “I think we can build a telescope that will be so easy to service it’ll be trivial for a robot to open a door, pull an instrument out, put a new instrument in and close the door. We just have to design it that way.”

Astronauts John M. Grunsfeld (proper) and Richard M. Linnehan (left) service the Hubble Space Telescope in low-Earth orbit on March 8, 2002. The risk of robotic servicing might considerably increase the science and speed up the event and launch of NASA’s Habitable Worlds Observatory, mission planners say.

Making HabWorlds robotically serviceable means the telescope can launch even when all of the devices aren’t prepared. As it stands, a few of the ideas Feinberg and his colleagues are contemplating even embrace an empty instrument bay for future filling-in. And the devices that launch with HabWorlds don’t must be the fanciest, most refined issues we are able to construct; they solely must be ok till we substitute them with extra succesful, next-generation {hardware}. In some ways, making the observatory serviceable might pay for itself. But if the telescope’s devices can change, this makes what should keep mounted—specifically, the scale of HabWorlds’ mirror, or aperture—all of the extra essential.

“Let’s focus on aperture, and if we have to compromise on the instruments in the first round, that might be the smart way to go,” says Matt Mountain, an astronomer who has helped to plan a number of massive telescopes and is the present president of the Association of Universities for Research in Astronomy.

The Mirror of Our Dreams

Beyond the potential of answering existential questions on extraterrestrial life, all of the scientific pleasure actually boils down to 1 massive factor: HabWorlds is prone to boast the most important, most secure starlight-gathering mirror ever despatched into house. But dimension doesn’t all the time play properly with different concerns, together with value.

More aperture equates to extra mild, extra decision, extra planets and extra science. A much bigger mirror also can imply fewer powerful engineering challenges down the highway. “There’s an obvious trade that exists between how many technologies you want to advance [to support high-contrast coronagraphy] and how large your aperture is,” Stark mentioned in his June presentation. With a bigger mirror, “you only have to advance a few of the difficult ones.”

And in concept, it’s straightforward to make a mirror very massive. You can break it into segments, as engineers do with ground-based telescopes, which then can dynamically regulate to perform like a single, strong reflective floor. That’s what Feinberg and his colleagues did with JWST, they usually’re eyeing the same design for HabWorlds. But with house telescopes, the essential query is: Just how massive of a mirror can we moderately launch?

“We are ultimately limited by our launch vehicles,” says Breann Sitarski, an optical engineer at GSFC and deputy principal architect of HabWorlds. Right now which means groups are taking a look at rockets with payload fairings between seven and 9 meters huge—SpaceX’s Starship, Blue Origin’s New Glenn and NASA’s Space Launch System.

Given these constraints, one choice is to design a segmented mirror to suit as-is throughout the fairings; one other is to make a mirror that, like JWST’s, folds up for launch after which unfurls in house. Teams at the moment are finding out two designs for HabWorlds. One features a mirror that may be a minimum of 6.5 meters in diameter, and the opposite makes use of a foldable mirror that may be a minimum of eight meters throughout.

“You don’t want too many potential points of failure, but we do have heritage from JWST on folding mirrors, so that’s one of the reasons we’re looking at it,” Sitarski says. “The launch vehicle size is one thing, but it’s also the complexity of the deployment.”

Additionally, for HabWorlds to picture exo-Earths, the telescope have to be ultrastable. Regardless of the mirror’s dimension, to brush away undesirable starlight, every of its segments should exactly align to inside picometers of each other—that’s, inside about one trillionth of a meter. This stage of precision is the equal of measuring the space between the Earth and moon to throughout the size of a grain of rice. Adding to the problem, every second the system will likely be making minuscule changes to all of the related elements to keep up clear, crisp imaging. As far-fetched as this requirement could seem, the members of the HabWorlds group are assured that they’ll meet it. “We’re on the verge of being there,” Sitarski says.

Ultimately, dimension will not be one thing that scientists are eager to compromise on. Many are pushing for the bigger choice of an eight-meter-class mirror. Such a giant, starlight-catching beast would make it simpler to characterize the atmospheres of Earth-size worlds and, particularly, to seek for telltale molecules within the near-infrared. In some methods, a bigger mirror means the distinction between discovering potential biosignatures and easily discovering life—having extra mild and extra decision makes ruling out potential “false positives” a lot simpler. And we’re studying that finding out Earth-size worlds is tough to do with something smaller. Even the mighty JWST is having bother assembly that problem because it scrutinizes rocky planets orbiting smaller, dimmer crimson dwarf stars. Compared with Earth-sun analogues, such methods are simpler to watch—but in addition so completely alien that they’re very troublesome to interpret and perceive.

“Nothing would be more depressing than only finding one Earth-like planet where you’re not 100 percent sure whether it has life and you don’t have the sensitivity to do any more,” Mountain says.

Avoiding that irritating result’s one argument for constructing an even bigger mirror. “The other big argument for aperture is: What if you find nothing? What does it tell you about the abundance of life?” Feinberg says. “If you don’t have a big enough aperture, you don’t have the confidence to say much statistically about how rare life is—whereas if you have a bigger telescope, and you survey enough stars and Earth-like planets yet don’t find life, you can statistically say that life is pretty darn rare.”

Bigger mirrors are dearer, nonetheless, and in NASA’s politically charged venture planning, even marginal budgetary fluctuations can imply the distinction between enduring assist and abrupt cancellation. Thomas Zurbuchen, NASA’s former chief of science, was an early supporter of HWO and initiated its first technical examine weeks after the discharge of JWST’s first pictures. He urges groups to be pragmatic, to defend in opposition to the attract of bigger-is-better—a mistake, he says, that nearly killed JWST. “Do a mission you can be proud of, but don’t prematurely fall in love with the wrong one,” he says. “I’d rather have a HabWorlds that looks at 15 exoplanets than one that looks at zero because I couldn’t afford it.”

There’s extra behind such warning than simply the teachings of JWST. NASA has pursued a HabWorlds-style mission earlier than—a 2000s-era effort referred to as the Terrestrial Planet Finder (TPF) that was finally deserted after astronomers, policymakers and company officers didn’t win broader assist from the astrophysics neighborhood and couldn’t completely agree on a most well-liked design, not to mention a practical price ticket. Although now only a historic footnote, to those that keep in mind, TPF stays a cautionary story, a warning of how a venture’s internecine combating could cause the complete effort to falter and fail.

An Uncertain Future

The challenges for HabWorlds, a minimum of proper now, appear to be extra political and fewer technological.

No scarcity of dire portents exist to make the sunny optimism of this summer time’s convention appear to be little greater than futile coping. The destiny of federally funded U.S. science has but to be determined, but when the Trump administration will get its approach, the nationwide analysis enterprise will likely be remodeled right into a flimsy husk of its former self, scarcely able to supporting HabWorlds and different visionary initiatives. No science company, not even NASA, will likely be spared; analysis at universities will sputter and decline; scientists and college students will search for alternatives overseas. Macroeconomic results from different coverage selections—akin to runaway deficit spending and the White House’s tariff-fueled commerce wars—might additional speed up and amplify the downward spiral.

“I’m not worried about the science [of HabWorlds]; I’m not worried about the experiments we design,” Shkolnik says. “I’m worried about losing people. If we lose the people with expertise and experience, then we will just be relearning the same lessons. We’ll figure out how to do it, but it won’t be the fastest, most efficient way—and it won’t be the cheapest.”

Congress, which carries the constitutionally granted energy of the purse, has signaled its intent to keep away from this bleak future—to battle, actually, for the putatively pro-science objectives the president himself often proclaims and celebrates in government actions, public speeches and social media posts. The ruinous therapy of federal science, many researchers and policymakers say, arises not from Trump however from certainly one of his most disruptively ideological appointees: Russell Vought, the ultraconservative bureaucrat in command of the White House’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB). In their proposed science appropriations payments, each congressional chambers largely rejected Vought’s machinations, though the OMB is pursuing methods to evade congressional oversight and set U.S. science on a collision course with mediocrity.

In fact, simply because the scientific course of can’t show a detrimental assertion, it’s laborious to argue {that a} world with out HabWorlds can be materially worse off. The similar might have been mentioned within the Nineteen Thirties of strategies to assemble the Empire State Building or within the Sixties of proposals to ship U.S. astronauts to the moon.

But historical past tells us, time and time once more, how even seemingly small acts can have outsize results that profoundly form actuality and our place inside it. If nothing else, the Apollo lunar missions gave Americans a motive to search for once more in unison, as monumental sociopolitical unrest wracked the U.S. The Empire State Building’s spire grew to become a towering beacon of progress on New York City’s skyline, whilst nearly insufferable financial hardships unfolded at its base. Such grand initiatives broaden the horizons of our hopes and desires.

Maybe within the fullness of time, HabWorlds and its quest for exo-Earths would be the similar—shiny factors of sunshine shining in opposition to a really darkish background, illuminating and without end altering our sense of the place—and what—we actually are.

“I think it’s that kind of enthusiasm which allows us to carry these projects through all of the ups and downs that we’re going to face between now and actually getting this launched,” Mountain says, “because it’s going to be a journey.”

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/are-we-alone-nasas-habitable-worlds-observatory-aims-to-find-out/

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us