This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.digitalcameraworld.com/photography/portrait-photography/richard-avedons-american-west-what-todays-portrait-photographers-can-still-learn-from-this-classic-series

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us

When the style and portrait photographer Richard Avedon (1923-2004) drove into the American West in 1979, he left behind the managed perfection of his vogue work and the glamour of movie star portraiture. What he discovered would produce one of the studied portrait collection in photographic historical past.

Now, as international artwork community Gagosian prepares to exhibit uncommon prints from In the American West at its Grosvenor Hill gallery, the collection affords modern photographers a well timed lesson in stripping portraiture again to its necessities.

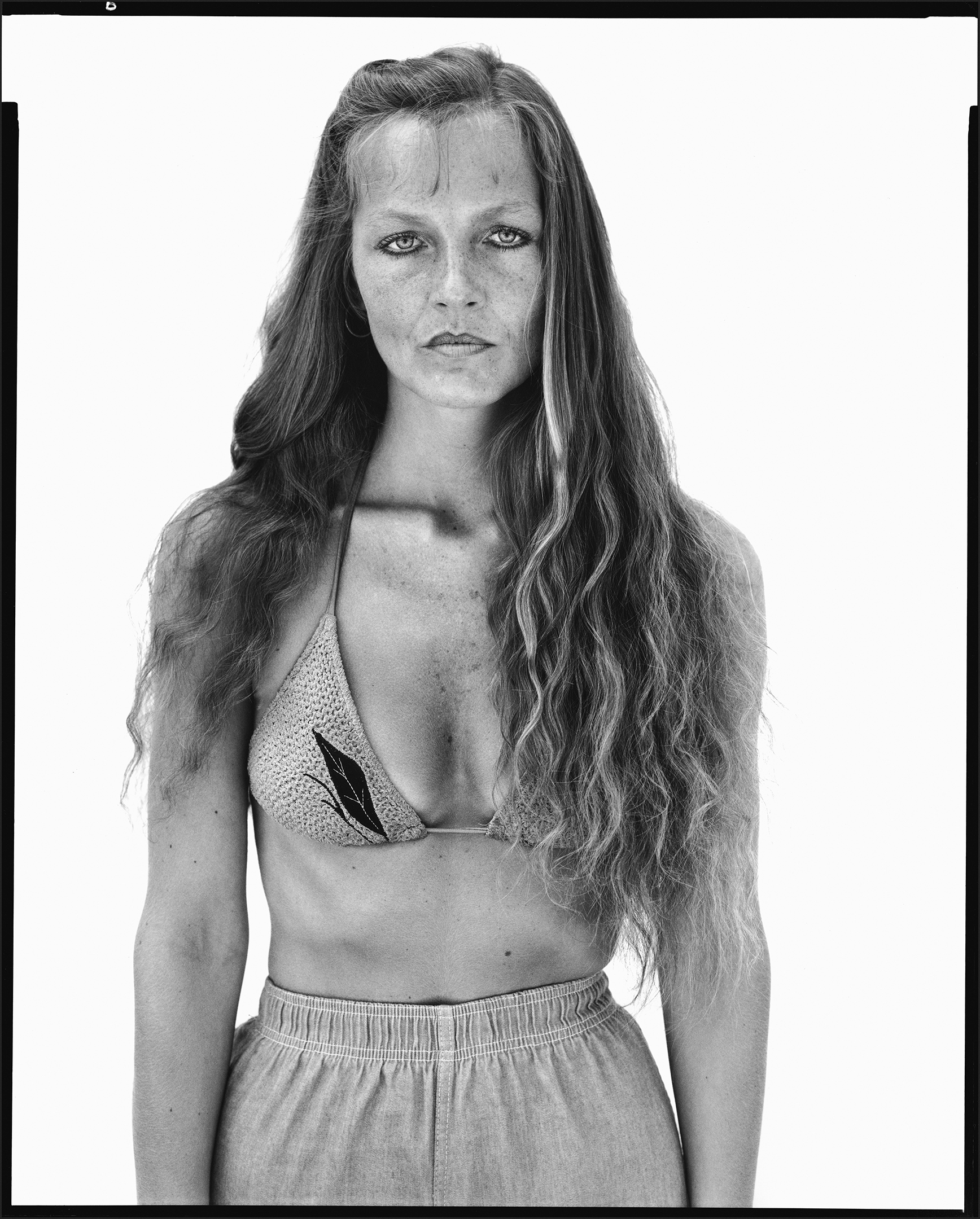

Avedon’s technical setup was deceptively easy: an 8x10in Deardorff view digicam, pure mild and a white seamless backdrop transported to areas throughout 21 states. No studio, no assistants dealing with elaborate lighting rigs, no post-production wizardry.

Yet these constraints produced photos of startling emotional energy. Coal miners, drifters, ranchers and slaughterhouse employees stare immediately on the digicam with an depth that transcends their circumstances.

Formal rigor

What made Avedon’s approach radical wasn’t the minimalism – August Sander had pioneered systematic documentary portraiture decades earlier – but the collision of his fashion photographer’s eye with documentary intent.

He treated these ordinary men and women with the same formal rigor he’d applied to Marilyn Monroe and Dwight Eisenhower. The white backdrop, borrowed from his commercial work, became a democratic space where a drifter commanded the frame with the same authority as any celebrity.

For photographers working today, when portrait sessions often involve multiple lights, reflectors and digital manipulation, this methodology is instructive. Avedon’s portraits work because of what’s absent.

The featureless background eliminates context that might sentimentalize or explain. We see only the person, their clothing, their posture, their gaze. The black film rebate visible around each frame reminds us that what we’re seeing hasn’t been cropped or adjusted; this is the complete, unmanipulated negative.

Longform examination

Starting in January, this exhibition – curated by Avedon’s granddaughter Caroline Avedon – includes works unseen since 1985; most notably the diptych of rancher Richard Wheatcroft photographed in 1981 and 1983. View the images casually and Wheatcroft appears unchanged; study them and you’ll notice how two years of ranch work have altered his stance, weathered his skin, worn his clothes. This is photography as long-form observation, something Instagram’s instant gratification culture has largely abandoned.

Avedon’s method was both confrontational and collaborative. He positioned himself next to the camera rather than behind it. This wasn’t photojournalism’s invisible observer; it was direct engagement.

The resulting images feel like encounters rather than observations. The sitters knew they were being photographed and chose how to present themselves, yet Avedon’s presence drew out something beneath the surface.

Is this exploitation?

The project drew criticism on its 1985 debut. Some accused Avedon of exploitation; others questioned whether a New York fashion photographer could authentically represent working-class America. It’s a debate that still rages, and not just about Avedon. For instance, I got some pushback from old friends recently, when I wrote this glowing obituary of Martin Parr – whom many accuse, similarly, of having indulged in “poverty porn”.

Personally, though, I don’t see this Avedon project as condescension; more a recognition of dignity in labour. For me, what endures most is its formal achievement. Each portrait balances documentary honesty with compositional precision. For instance, Avedon shot James Story, a coal miner covered in soot, with the same reverence Renaissance painters applied to martyred saints.

More broadly, for contemporary photographers drowning in gear lists and editing software, In the American West is a reminder that equipment matters less than approach, and demonstrates the value of sustained commitment. After all, Avedon conducted over a thousand sittings to produce 126 editioned images. In total, he spent half a decade spent returning to the same communities, building trust, understanding his subjects beyond a single shutter click.

Forty-seven years on, as the series resurfaces in London, its lessons remain surprisingly practical. Simplify your setup, engage with your subjects directly, commit to projects deeply rather than broadly, and trust that honest observation will reveal more than elaborate staging ever could.

Richard Avedon: Facing West opens 15 January 2026 at Gagosian Grosvenor Hill, 20 Grosvenor Hill, London W1K 3QD. Open Tuesday–Saturday, 10am–6pm.

Check out our choose of the 50 biggest photographers ever

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.digitalcameraworld.com/photography/portrait-photography/richard-avedons-american-west-what-todays-portrait-photographers-can-still-learn-from-this-classic-series

and if you wish to take away this text from our web site please contact us