This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/museum-life/armour-and-lace-women-photographers-in-19th-century-institutions

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

Photography inside museums is most frequently understood by way of the lens of artwork historical past, as a artistic or aesthetic apply. Yet, images additionally features as an important institutional instrument—an equipment by way of which museums and establishments doc, classify, and disseminate data.

The historical past of museum images undertaken not for inventive show, however to maintain the day by day operations of amassing, cataloguing, instructing, and alternate, is a historical past written in males’s names, specializing in Roger Fenton on the British Museum or Charles Thurston Thompson on the South Kensington Museum (now the V&A). Yet hidden in plain sight inside the archives of Europe’s nice establishments such because the V&A, the Louvre and the Prado is proof that ladies had been additionally shaping the visible tradition of those museums.

My doctoral analysis, Armour and Lace: Women Photographers in Nineteenth-Century Institutions, seeks to recuperate the ladies whose skilled labour underpinned these practices and to disclose how their contributions formed the visible tradition of the fashionable museum.

Looking for ladies within the body

The venture started within the V&A’s archives, the place greater than 150,000 Nineteenth-century images are listed within the historic accession registers. Among them, I recognized almost 8,000 made by girls. I discovered that the majority of those girls had been unbiased professionals photographing in establishments.

What united them was not type or topic however circumstance: all operated inside the new bureaucracies of establishments that had been formalising data by way of images. These establishments—repositories of artwork, science, and empire—wanted pictures to catalogue, train, and flow into objects. Women equipped that labour.

Their tales had been hiding in plain sight, buried in accession registers, ledgers, guard books and in dusty darkish corners of missed museum storage areas. Bringing them ahead meant studying acquainted sources in a different way—asking, as an illustration, who signed the detrimental, who acquired the fee, beneath whose identify is the patent or copyright, and even who lived within the museum residences. Once these questions had been requested, girls started to appear all over the place.

Work, marriage, {and professional} identification

In some instances, the financial vulnerability ensuing from widowhood, additionally paradoxically, opened doorways. This was aided by way of household connections to the establishments they served. Isabel Agnes Cowper, for instance, after the loss of life of her husband in 1860, began working together with her brother, Charles Thurston Thompson, the V&A’s Official Museum Photographer. When Thurston Thompson subsequently died in 1868, Cowper leveraged her familial networks and took on his function. She and her 4 youngsters had been quickly recorded dwelling at ‘3 The Residences’ on the museum, blurring distinctions between home {and professional} area.

Cowper went on to run the museum’s photographic studio for 23 years, producing 1000’s of pictures that documented the whole lot from vintage lace to monumental plaster casts. While her labour, recorded within the museum’s correspondence, was compensated on a per piece foundation – her employment was regular, technical, and important. Yet her authorship was not often acknowledged in an archive organised by object fairly than maker, erasing her contribution even because it preserved her labour.

Jane Clifford, additionally a widow, labored in Madrid documenting treasures within the Spanish Royal Collection (now the Prado). Exploiting her deceased husband Charles Clifford’s status as photographer to the Spanish Royal Family, Clifford was commissioned by John Charles Robinson, the V&A’s famend curator. Letters between Clifford and the V&A present her negotiating charges and supply schedules. She was paid for her experience in the identical method her male friends had been, but her authorship was lengthy absorbed into that of her husband – till proof within the archives separated their skilled identities.

This pressure between visibility and invisibility runs all through the historical past of girls’s institutional images. Many had been recognized to their contemporaries – paid, typically publicly praised – however their identities light as institutional credit score changed particular person attribution. Recognising their names at present permits us to see not solely what they made however the institutional constructions that made their obscurity potential.

Marital standing was not the one social determinant shaping girls’s photographic careers. Class mattered too. These photographers had been middle-class girls, many with inventive coaching. They operated as professionals – submitting invoices, launching publishing ventures, and corresponding with curators and administrators.

Louise Laffon in Paris, as an illustration, photographed the celebrated Campana Collection within the 1860s on the Musée Napoléon III (now the Louvre). She monetised her institutional entry and bought her meticulous albumen prints to collectors and academic establishments by way of subscriptions. Archival fee information reveal state acquisitions of her images—proof that her work was not a pastime however a enterprise.

By tracing funds, contracts, and copyright deposits, the image adjustments: girls had been incomes livelihoods from institutional images, working inside networks of alternate that linked science, artwork, and schooling throughout Europe.

Photographing science

While some girls photographed sculpture and ornamental arts, others turned their lenses towards scientific topics. Ok. Marian Reynolds, working for London’s Natural History Museum and the Royal Institution within the Nineties, produced pictures of chook eggs, laboratory interiors, and Faraday’s experimental equipment. Her correspondence with museum and institutional officers reveals a excessive regard for her ability documenting shows.

Reynolds’s images had been later utilized in scientific lectures and publications, situating her inside the visible infrastructure of data manufacturing. Yet she was seldom credited. Her case demonstrates how girls’s mental labour in science was usually refracted by way of institutional anonymity.

At the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, Alice Everett, Edith Rix, and Annie Russell labored as ‘computers’ and ‘observers,’ photographing the celebs for the Carte-du-Ciel venture. Their duties—exact, repetitive, technical—anticipated the data-processing roles girls would occupy in twentieth-century computing. Like Cowper, Laffon, Clifford and Reynolds, they had been nameless professionals embedded within the equipment of institutional analysis.

Art, but additionally paperwork

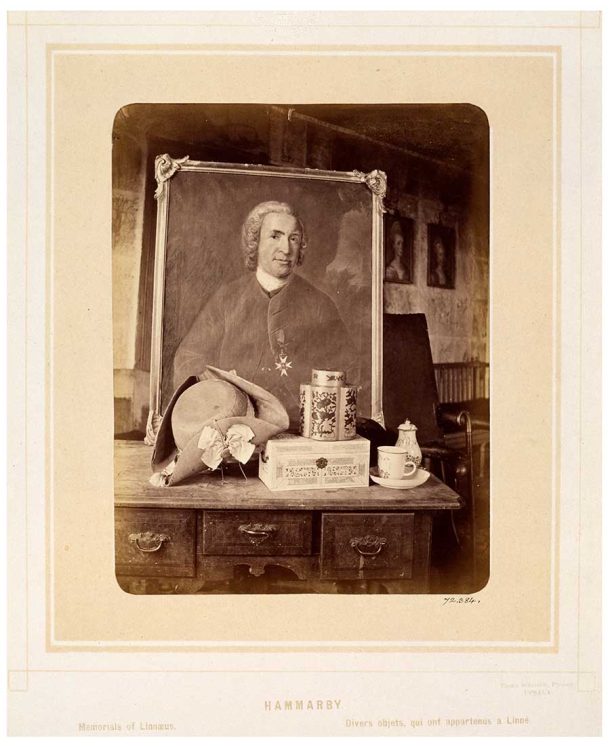

My evaluation discovered that the definition of Nineteenth-century institutional photographer is advanced and demonstrates the necessity to query modern definitions of artwork images in Nineteenth-century establishments. I appeared on the celebrated photographer Julia Margaret Cameron recognized for her conviction that images was an artwork type. Yet, Cameron equipped images to the V&A for use as pedagogical instruments categorised as ‘Studies for artists’. Similarly, Swede Emma Schenson’s nostalgic views of locations and issues related to the archive of botanist Carl Linnaeus, had been accessioned into the V&A set as examples of ‘Nordic architecture’. In each instances, these girls contributed works that blurred the boundary between ‘art’ and ‘document’.

Visibility and circulation

One of the central questions in my analysis was how these girls’s pictures moved by way of institutional and public area. Once produced, a museum {photograph} entered advanced techniques of circulation: one print could be mounted in a reference album, one other utilized by a design college, a 3rd reproduced in an illustrated e-book. Their images circulated internationally by way of exchanges between museums and later inside the business picture economic system that flourished with the arrival of photomechanical printing strategies. Each replica multiplied its attain whereas erasing its maker. The {photograph}’s authority grew because the photographer’s identify disappeared. It’s a sample that echoes the broader taxonomies of Nineteenth-century establishments, which valued collective authorship over particular person identification.

Why these histories matter

As images historians Elizabeth Edwards and Ella Ravilious remind us, establishments are ‘places where objects are assembled and become knowledge.’ The girls who photographed these objects participated immediately in that course of. Their work formed how generations encountered artwork and science: college students studying from V&A catalogues illustrated with Cowper’s images, scientists finding out Reynolds’s pictures of specimens, or producers, artists and designers gaining inspiration from Clifford’s report of royal treasures. These images had been by no means simply information; they had been devices of pedagogy and creativeness.

Abigail Solomon-Godeau has written that invoking the photographer’s gender shouldn’t be about evaluating inventive high quality however about revealing ‘that however occluded or ignored, women have always been part of photographic history as both players in and agents of its developments.’ That perception captures what I discovered within the archives: girls weren’t exceptions to the rule however integral to the evolution of images inside trendy establishments.

Up till not too long ago, Nineteenth-century girls photographers had been usually solid as genteel ‘lady’ amateurs. Excavating these skilled girls’s narratives does greater than fill historic gaps within the historical past of images, it additionally addresses related gaps in institutional histories and extra broadly, the historical past of girls’s labour. Today, because the V&A and the Parasol Foundation Women in Photography venture search to develop the tales we inform about photographic apply, the lives of Laffon, Clifford, Cowper, Reynolds, Cameron, Everett, Rix, Russell, and Schenson (and I discovered others!) symbolize a unique sort of skilled success than that measured by artwork historic methodologies, highlighting girls’s function producing and speaking data.

Dr Erika Lederman is a photographic historian and cataloguer of the Royal Photographic Society Collection on the Victoria and Albert Museum. Her doctoral analysis, ‘Armour and Lace: Women Photographers in Nineteenth-Century Institutions,’ was accomplished at De Montfort University in 2023 beneath an AHRC Collaborative Doctoral Award Scheme with the V&A.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.vam.ac.uk/blog/museum-life/armour-and-lace-women-photographers-in-19th-century-institutions

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us