This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.westword.com/arts-culture/denver-art-museum-unveils-unseen-portraits-in-what-weve-been-up-to-people-40839510/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

Thousands of images are quietly saved on the Denver Art Museum, rigorously catalogued, preserved and, more often than not, unseen. For Eric Paddock, the museum’s curator of pictures, that quiet has turn out to be unattainable to disregard.

“One of the frustrations is that you have all this stuff, and you can’t always share it with the public,” he says. “We do a lot of exhibitions. We do two exhibitions a year; sometimes we’ve done as many as three or four. But often those are things that we borrow from other artists or from galleries or other museums. So I just thought it was time to start getting out some of the stuff that we’ve been collecting.”

That impulse grew to become a sequence. Last 12 months, the museum debuted What We’ve Been Up To: Landscape. This weekend, the follow-up opens on stage six of the Martin Building: What We’ve Been Up To: People, on view February 8 by September 29. The exhibition gathers roughly “fifty photographs plus this big group of 46 pictures that are in the display case back here” from the museum’s everlasting assortment which have by no means been displayed in its galleries earlier than.

The present just isn’t organized round movie star photographers or well-known topics. Instead, Paddock approached the gathering {photograph} by {photograph}, asking what every picture needed to say about being human.

and Robert Adams.

“We are looking for good stuff,” he says. “We’ve approached each picture individually, and I wouldn’t say that there’s an overarching plan or philosophy, except to look really carefully and kind of gauge or read what these photographs, in this case, have to say about people and about the joys and the challenges of being human. I was going to say in today’s world, but some of these pictures were made much earlier, so that doesn’t necessarily float.”

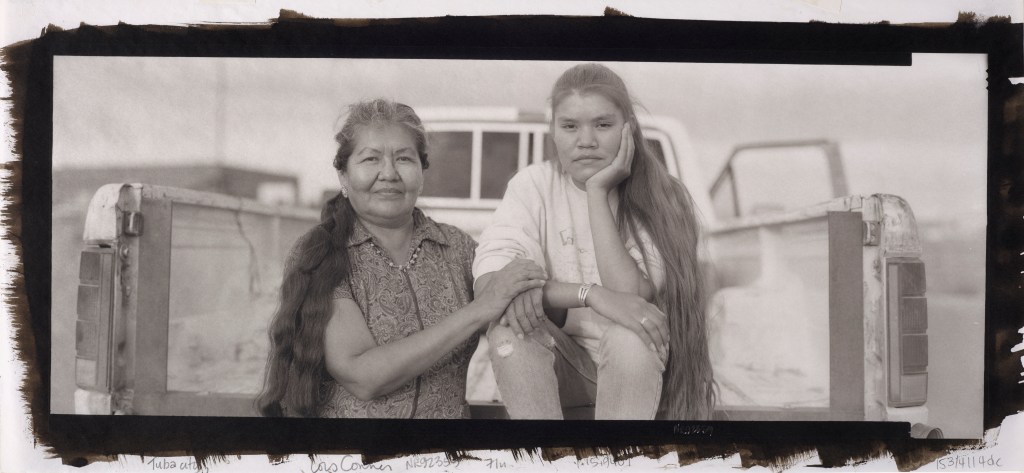

The result’s a gallery that strikes between continents, centuries and contexts with shocking fluidity. A 1912 portrait made in New Orleans by E.J. Bellocq hangs in the identical exhibition as modern self-portraits, candid road scenes, Polaroids of Andy Warhol and an Irving Penn picture of The Grateful Dead and Big Brother and the Holding Company. Some works are by internationally recognized artists. Others are by photographers whose names have been misplaced to historical past.

“Geographically, it’s kind of wide open,” Paddock says. “There are pictures by photographers in California, Nebraska, Mexico, Pennsylvania, New Mexico, Japan, Mexico and several that we don’t know who made or where they were made.”

Not each {photograph} even exhibits an individual. One picture by Japanese photographer Yoko Ikeda options solely a scattering of pink slippers pointed in numerous instructions. Paddock positioned it alongside a sequence of pictures linked by a quiet visible joke about ft, absence and movement: a long-exposure crowd in St. Petersburg leaving footwear on the steps, a returning prisoner of struggle on crutches, a affected person dancing along with his ft cropped out of body and a lady transferring so shortly her leg fails to register on movie.

“I don’t really expect anyone to put all that together,” he admits. “It was just my little conceit, as we were figuring out what to include in the show.”

Elsewhere, refined themes emerge if guests step again. A wall of youngsters at play offers solution to images associated to meals, then to contemplative portraits, then to self-portraits. In one, an artist wears a jacket and tie that match the wallpaper to mix in, creating a visible metaphor for isolation. A quiet Vanitas part close by options pictures referencing mortality, comparable to a life masks, skulls unearthed from an unmarked grave, and corroded canisters of cremated stays from an deserted hospital.

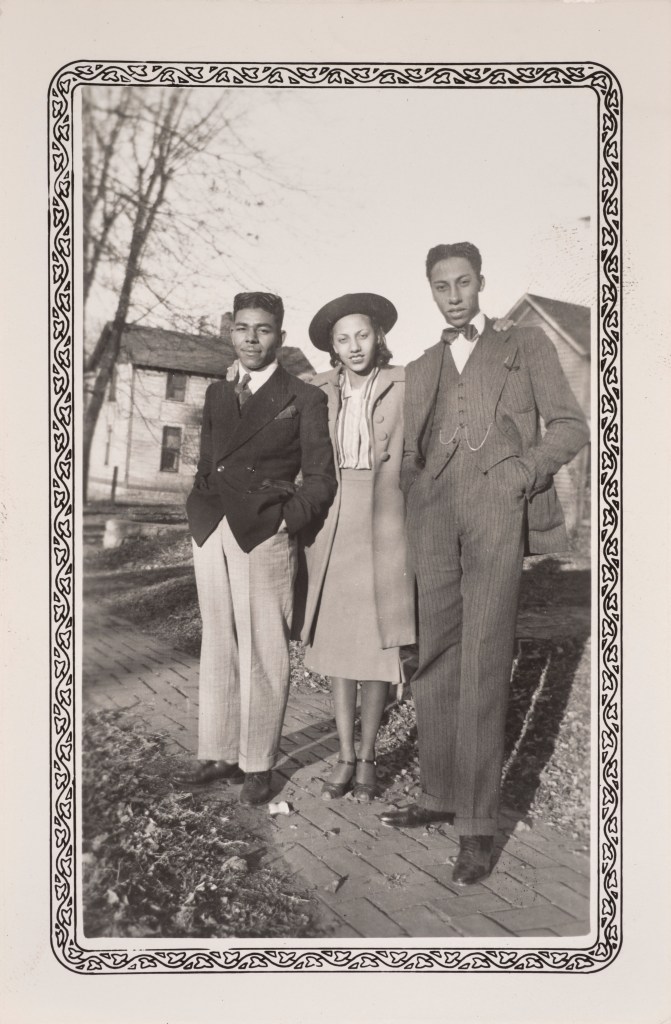

Untitled, Topeka, Kansas, 1924-30. Gelatin silver print; 4 x 2 3/8 inches. Denver Art Museum: Funds from the

Photography Acquisitions Alliance.

Courtesy of Denver Art Museum

“What I would like people to do is I would like them to look at the individual photos,” Paddock says. “But every once in a while, just step back and look at a wall segment.”

The emotional middle of the exhibition, nevertheless, sits inside an extended show case holding 46 small snapshots taken in Topeka, Kansas, between 1924 and 1930. The photographer is unknown. The topics are Black resort workers, photographed on a rooftop of their uniforms, then outdoors on the road and eventually in neighborhood scenes with family and friends.

Paddock acquired the pictures in the course of the pandemic after recognizing them behind an public sale catalog. No one bid on them. He made a suggestion, rallied a small group of acquisition donors and introduced the pictures to Denver in 2020. He’s been ready to indicate them ever since.

“Honestly, this might be the whole reason we’re doing this show,” Paddock says. “…I really wanted people to see these. I just think they’re charming; they’re fascinating. For me, they go straight to the heart in a way, and there’s such innocence in some respects.”

In one body, a person poses stiffly, not sure. In the subsequent, one other worker hams it up for the digital camera, pant cuffs rolled, leaning arduous into the second. In one other, a lady seems to bounce because the photographer’s shadow cuts throughout the bottom. There are hints of personalities, relationships and inside jokes, frozen in silver halide almost a century in the past.

“Each of these pictures, you look at the people and the way they pose and the way they look at the camera and the way they sort of manage their uniforms,” Paddock says. “They’re all just like these little hints at those people’s personalities. And to me, each one of these people, as you look at the picture, becomes absolutely real and individual.”

For Paddock, the deeper lesson of the exhibition is one thing pictures has taught him over a long time of wanting.

“Looking at photographs, I kind of learned that people don’t change that much,” he says. “Everyone kind of wants the same things. Everyone fears the same things and that’s part of what it is to be human.”

The concept that we’re all the identical no matter time, geography or circumstance is what unites the exhibition.

“The idea is to show a lot of different kinds of people, different ages and different backgrounds and we’ll talk about them individually,” Paddock says. “We are doing this as a way of reminding ourselves and the world that we’re all in this together.”

What We’ve Been Up To: People is on view from Sunday, February 8, by Tuesday, September 29, on the Denver Art Museum, 100 West 14th Avenue. Parkway. Learn extra at denveratmuseum.org; the exhibition is included on the whole museum admission.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.westword.com/arts-culture/denver-art-museum-unveils-unseen-portraits-in-what-weve-been-up-to-people-40839510/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us