This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2026/feb/18/he-couldnt-be-happier-celebrating-william-egglestons-incredible-photography

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

As a small little one, Winston Eggleston was solely vaguely conscious that his father, William Eggleston, was a well-known photographer. For all he knew different youngsters additionally had dad and mom who have been associates with Dennis Hopper, or who spent hours tinkering on a piano between occasional, fevered pictures sprees, or who had taken the world’s most iconic image of a purple ceiling.

“It’s all normal to you, because you don’t know anything different,” Winston lately recalled. “Looking back, I was lucky.”

But he was intrigued by the yellow packing containers of Kodak movie he noticed mendacity round his home, and by an odd, sour-smelling paper on which his father sometimes printed images. These have been supplies for dye-transfer, a particular method used to print trend and promoting pictures of exceptionally vibrant coloration. As one of many first artwork photographers to embrace coloration pictures – at a time when the artwork world regarded coloration as vulgar – Eggleston started utilizing dye-transfer, within the Nineteen Seventies, to provide his pictures a startling Technicolor pop.

When Kodak discontinued its dye-transfer merchandise within the Nineties, the Egglestons started shopping for up any shares they might discover. They additionally started a troublesome venture: deciding which of William Eggleston’s 1000’s of pictures would possibly take pleasure in a last blaze of color-saturated glory. In the top solely about 50 pictures may make the reduce.

Thirty-one of them are included in William Eggleston: The Last Dyes, an exhibition via 7 March on the David Zwirner Gallery in New York. The present often is the final ever exhibition of images, by Eggleston or anybody else, produced utilizing dye-transfer. When I visited the Chelsea gallery on a ferociously chilly and windy current Saturday, greater than a dozen folks, some with youngsters, had endured subzero temperatures to see them.

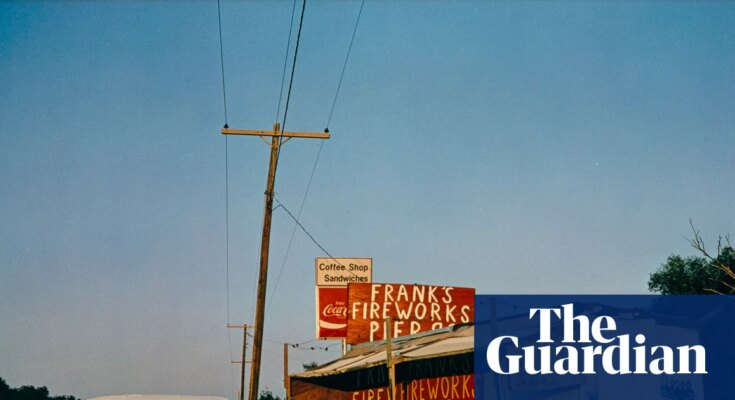

Even after having had dye-transfer defined to me a number of occasions, I’m unsure I completely perceive the technical features of the process. But the outcomes converse for themselves: the brick reds, indigo blues, canary yellows, sundown pinks and verdant greens of Eggleston’s work dazzle towards the white partitions of the gallery. One {photograph} beckons the viewer down a darkish, greenish hallway towards a toilet glowing an infernal purple, as if the bathroom, seen from an extended low angle, have been the throne of Satan himself. (Unsurprisingly, Eggleston and David Lynch have been followers of one another’s work.)

The texture of Eggleston’s pictures can be expressed to vivid impact – lifeless leaves, the pebbled steel of a automotive inside, the sandpapery concrete round a desolate swimming pool.

The pictures are a mix of Eggleston’s “big hitters” and “stuff that had never been printed before”, Winston, 53, advised me. He was talking by video-call from his dwelling in Memphis, at a property the place his father additionally now lives; behind him was a framed print of one in all Eggleston’s works. Winston wore a marled gray sweater, blue striped shirt and black baseball cap – a extra informal iteration, maybe, of his father’s southern-fried Savile Row aesthetic of darkish fits and bowties worn undone like string ties.

For years Winston and his brother, William III, have been working with their father, now 86, to archive and protect his work. The dye transfers have been executed by Guy Stricherz and Irene Malli, a married couple who’re among the many last remaining specialists of the costly and laborious course of. Each batch of 10 pictures took six to eight months, generally longer, to print.

Like the dye-transfer prints, the pictures of The Last Dyes, taken between 1969 and 1974, really feel like paperwork from a world that was maybe already vanishing – an American south of derelict drive-in theaters, rusted steel promoting and Oldsmobiles.

Yet when Eggleston debuted his work, at a infamous 1976 exhibition at Moma, it was novel to the purpose of polarizing. Color pictures had existed for many years, however most severe artwork photographers labored in black-and-white, and they didn’t typically take pictures of bogs or glasses of iced tea. In a book for the brand new present, the author Jeffrey Kastner argues that the legend that the Moma present was universally panned has been overstated; it’s true, although, that many critics have been unimpressed with Eggleston’s snapshot-style pictures of the on a regular basis, which struck them as about as fascinating as a random particular person’s trip Polaroids.

Time has been kinder to Eggleston’s capability to see magnificence within the ugly, cheesy or mundane – to wage “war with the obvious”, as he has put it. He is now considered one of the crucial essential dwelling American photographers, and retrospectives of his work have drawn keen audiences lately in Berlin and Barcelona. Christie’s auctioned plenty of 36 of his images for nearly $6m in 2012. (Although he listens principally to classical music, his pictures have additionally graced the covers of a number of rock albums.)

Eggleston’s pictures are inclined to really feel decontextualized. They shouldn’t have titles or captions, and he’s hostile to interpretation. “Words and pictures [are] like two different animals,” he advised the New York Times in 2016. “They don’t particularly like each other.” And whereas he has generally been keen to recall the origins of particular pictures, he works shortly and takes solely a single image of every topic, so he can’t at all times bear in mind their precise provenance.

Most of the Nineteen Seventies images have been taken in Memphis or throughout highway journeys round Tennessee, Mississippi and Louisiana. “Dad was not one of those artists who got up every day and went out working,” Winston stated, wryly. “He worked very sporadically, in short bursts.” Winston was too younger to have been current when Eggleston took many of the pictures, although he can hint a few of them.

As he spoke, he flipped via the brand new ebook, pausing at a few of Eggleston’s most iconic photos. A younger girl in pink, gazing over her shoulder from a church pew? Taken on the funeral of the blues musician Fred McDowell. A person sitting subsequent to a maternal-looking quilt, brandishing a revolver? He was a distant relative – or maybe a household pal; Winston can’t fairly bear in mind – who labored because the nightwatchman of a tiny Mississippi city.

The exhibition additionally features a photograph of a blue ceiling that echoes Eggleston’s better-known red one. It was taken on the identical home – of a pal of Eggleston’s who was later believed to be murdered – and is equally placing. Although contemporaneous, it now seems like a smiling nod to the opposite photograph.

“For many years, it was, ‘Should we print it?’ ‘Eh, it’s too derivative of the red ceiling,’” Winston stated. “And finally, we’re like, well, of course we should print it! I mean, this is it – and I’m really glad we did.”

Decades of bourbon and cigarettes, plus experimentation with substances in his youthful years, have someway not restricted his father’s longevity. But he has been pressured to decelerate, Winston stated. He just isn’t as cell lately, which makes pictures troublesome, and has lived quietly since his long-suffering however beloved spouse of a half century, Rosa, died in 2015. Their daughter Andra, a dressmaker, has a textile line impressed by his artwork.

The last photograph within the new ebook is a proto-selfie that Eggleston took someday within the Nineteen Seventies: his head lies horizontally on a pillow, dealing with the viewer, eyes closed in calm repose. Eggleston is now, little question, eager about his legacy. “He couldn’t be happier about the new show,” Winston stated. “He loves the new catalogue. It’s funny, though – I don’t think that he’s totally accepted the fact that the dye-transfer is over.”

Winston has elsewhere described his father’s work as “democratic and neutral” – an outline that echoes a title that Eggleston as soon as gave his work, The Democratic Forest, and one which Eggleston’s angle towards his work would appear to replicate. According to Winston, his father doesn’t choose any of his pictures over any others. He likes all of them equally, and leaves the enhancing of his collections to different folks.

Winston as soon as requested his father which of his pictures, if pressured to decide on, he thought of his favourite or his greatest. “His answer,” he stated, “was, ‘Well, I guess I’d have to go into a room and turn the lights off, throw them all up in the air, and grab one.”

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2026/feb/18/he-couldnt-be-happier-celebrating-william-egglestons-incredible-photography

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us