This page was generated automatically, to view the article in its original setting you can access the link below:

https://www.npr.org/2025/01/12/nx-s1-5254719/kangaroo-species-went-extinct-in-the-pleistocene-research-hops-in-with-a-possible-explanation

and if you wish to remove this article from our website please get in touch with us.

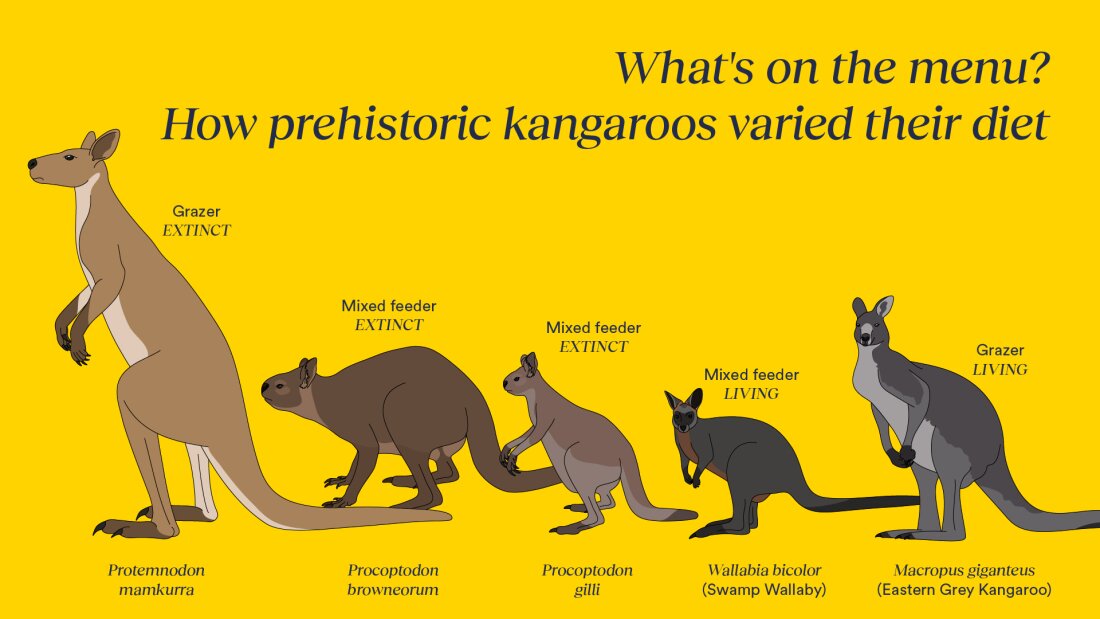

Scientists aimed to uncover the reasons behind the extinction of ancient kangaroos by examining the teeth of over 900 modern and extinct kangaroo species.

Traci Klarenbeek/Megafauna Central

hide caption

toggle caption

Traci Klarenbeek/Megafauna Central

Thousands of years ago, in the late Pleistocene, a multitude of large animal species were simply eliminated from Earth during a widespread extinction event. In Australia, around twenty kangaroo species disappeared — but the cause remains unclear.

“It’s a dilemma that has troubled paleontology for several centuries,” remarks Sam Arman, a paleontologist at Megafauna Central, a museum dedicated to natural history in Australia.

Recent research published in Science, indicates that Arman and his team suggest a thorough examination of numerous ancient and contemporary kangaroo teeth points to the advent of humans in Australia having a greater impact on the extinction event than climatic changes.

Despite this, not all are in agreement. “I believe evaluating a single moment in time is insufficient to dismiss the influence that climate might have in previous extinctions,” states Larisa DeSantis, a paleontologist at Vanderbilt University who was not part of the research.

The debate over human versus climate-driven extinction is significant, as it may aid scientists in untangling the factors that are currently affecting the decline of global biodiversity.

Kangaroo origins… and conclusions

Kangaroos originated from a possum-like ancestor approximately 20 million years ago. Then, around eight million years ago, “Australia turned increasingly arid,” explains Arman.

In response, kangaroos modified their movement and feeding habits to adapt to the drier atmosphere. “That was when kangaroos truly flourished — or maybe I should say they hopped — and diversified into numerous groups,” remarks Arman.

Two significant groups of kangaroos existed. The first had elongated faces, “which is what you still observe today, including species like wallabies,” explains Arman. The second consisted of short-faced kangaroos. “If you placed a koala’s head on top, you’d be in approximately the right range, just not as fluffy.”

All these kangaroos coexisted with various other creatures. “We had a marsupial comparable in size to a rhinoceros,” Arman shares. “There was also a marsupial lion. All kinds of extraordinary creatures existed.”

However, around 40,000 to 65,000 years ago, the majority of these large animal species became extinct, including all the short-faced kangaroos and some long-faced ones. The question remains — what caused this?

The first postulates whether humans — who settled in Australia at around this time — had a role in the extinction, possibly through hunting or modifying the environment.

The second theory pertains to climatic alterations. “If these kangaroos were solely feeding on certain types of vegetation,” suggests Arman, “then perhaps climate change led to the extinction of those plants, resulting in their demise.”

Ancient marsupial dentistry

This theory that the disappearance of their food led to extinction is based on the assumption that kangaroos were specialists in their diets. Some paleontologists support this view citing the variations in skull shape and chemical composition among kangaroos — suggesting that short-faced kangaroos primarily consumed shrubs while long-faced kangaroos fed mainly on grasses.

However, Arman had his doubts. “Adaptation does not necessarily define what one eats,” he states. He investigated the question of ancient kangaroo extinction by meticulously examining the teeth of over 900 kangaroos — encompassing fossils from Victoria Fossil Cave in South Australia and modern specimens from around the nation.

The method employed is known as dental microwear texture analysis. “Whenever an animal gnaws on its food,” Arman elucidates, “the food leaves traces — microscopic scratches on the teeth’ surface. By scanning these teeth under an ultra-high resolution microscope, we can compare the diets of these ancient creatures.”

Arman and his collaborators discovered that most of the extinct kangaroos (both short- and long-faced varieties) had varied diets. In other words, he suggests they consumed both grasses and shrubs depending on what’s available. The implication, as Arman proposes, is that starvation due to climate change may not have been the sole reason for the demise of all those kangaroos. Instead, it could have been the arrival of humans.

“This does not exclude the possibility that climate change played a role in some other capacity,” states Arman, “but narrating the story without acknowledging humans is challenging.”

DeSantis points out that reconstructing the dietary habits of animals in Australia is difficult due to the diverse landscape. “This study is quite insightful,” she mentions, “but I think it may overstate the case — that these kangaroos were already well suited to changes in climate.”

She tends to favor the idea that climate change had a more substantial influence on their extinctions. “I believe a tipping point can exist,” she says. “If conditions become warm enough or sufficiently dry, these animals will struggle to survive, regardless of whether they are mixed feeders.”

DeSantis argues that the recent findings do not present a complete picture. “It’s crucial to see if we can untangle the effects of climate and humans in the past,” she insists, “so we can better grasp and predict the consequences we are inflicting on present ecosystems.”

This is a notion that Sam Arman concurs with. He is optimistic that his current and future endeavors might lead to strategies for supporting modern kangaroos — especially if these animals can adapt to a wider variety of plants and thrive in more ecosystems than previously thought.

“Especially for some of our species that are becoming increasingly rare,” he notes, “we could consider the possibility of reintroducing them in areas where they might initially appear ill-suited.”

In essence, Arman aspires that the kangaroos that faced extinction during the Pleistocene could aid today’s kangaroos in evading a comparable outcome.

This page was generated automatically, to view the article in its original setting you can access the link below:

https://www.npr.org/2025/01/12/nx-s1-5254719/kangaroo-species-went-extinct-in-the-pleistocene-research-hops-in-with-a-possible-explanation

and if you wish to remove this article from our website please get in touch with us.