This page was generated automatically; to view the article at its source, you can follow the link below:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ape-like-human-ancestors-were-largely-vegetarian-33-million-years-ago-in-south-africa-fossil-teeth-reveal-180985873/

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website, please reach out to us

:focal(700x527:701x528)/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/36/c7/36c784f2-7136-42eb-8967-be4f4cc29df9/smithsonian_feature_image.png)

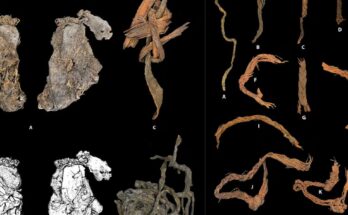

Hand-drawn illustration of two of the seven collected molars from Australopithecus

Dom Jack, MPIC

The primate-like human predecessor Australopithecus—possibly most recognized from the celebrated fossil ‘Lucy’—may not have included much meat in its diet. Following an examination of remains over 3.3 million years old from seven specimens in South Africa, researchers propose that these Australopithecus individuals were primarily herbivorous.

The recent research, elaborated in a study released last week in the journal Science, illuminates ancient eating habits utilizing the nitrogen ratios found in fossilized teeth.

“This technique opens exciting avenues for comprehending human evolution, and it poses vital questions, such as when did our forebears start incorporating meat into their eating habits?” remarks co-author Alfredo Martínez-García, an environmental scientist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry, in a statement. “And was the initiation of meat consumption linked to an expansion in brain size?”

Researchers theorize that the shift to meat consumption enabled our ancestors’ brains to increase in size and subsequently evolve the essential capacity to create and utilize tools. However, the precise timing and method of this transition remains ambiguous.

Lead investigator Tina Lüdecke stands beside “Little Foot,” an Australopithecus skeleton believed to be the most complete pre-human skeleton ever discovered. The specimen was unearthed in the Sterkfontein caves, South Africa, where the analyzed teeth were also extracted. Bernhard Zipfel / Wits University/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/c3/3b/c33bfa62-6532-4d1c-8a8f-a2a0633d8b20/low-res_pic_1.jpeg)

“Meat likely played a crucial role in the growth of cranial capacity—larger brain development—throughout human evolution. Animal resources present a highly concentrated energy source and are abundant in vital nutrients, minerals, and vitamins essential for sustaining a large brain,” comments study lead author Tina Lüdecke, a geochemist at the Max Planck Institute for Chemistry and the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa, in a conversation with Reuters’ Will Dunham.

However, Lüdecke and her associates’ latest findings imply that the shift to meat-eating did not occur during the lifetimes of the seven studied Australopithecus individuals, which lived between 3.3 million and 3.7 million years ago. This inference arises despite some indications linking certain Australopithecus specimens to stone tools.

“These hominins are still quite ape-like, with smaller brains, that already walked upright but exhibited a more ape-like gait,” Lüdecke tells NPR’s Nell Greenfieldboyce. “Here, for the first time, we possess actual data to indicate, ‘Alright, these small-brained hominins did not consume much meat.’”

The research team evaluated nitrogen isotopes—variant forms of nitrogen with differing neutron counts—in the fossilized tooth enamel from the Australopithecus remains. As food digestion in animals ultimately expels “light” nitrogen (14N) from the body, it elevates the body’s ratio of “heavy” nitrogen (15N) to 14N, relative to its food source. In simpler terms, the higher an animal is on the food chain, the greater its 15N to 14N ratio, as clarified in the statement.

Previously, scientists have studied nitrogen isotope ratios in “younger” organic remains like hair, claws, and bones to investigate the diets of humans and animals. For their recent study, however, the team innovated a technique to apply this method to tooth remains that are millions of years old.

“Tooth enamel constitutes the hardest tissue found in mammals and can preserve the isotopic signature of an animal’s diet for millions of years,” Lüdecke elucidates in the statement.

The Sterkfontein excavation location, where the Australopithecus fossils were uncovered. Dominic Stratford/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer_public/0f/6e/0f6e404d-d867-42fa-ba48-fbe717d46b02/low-res_pic_4.jpeg)

The researchers proceeded to compare the 15N to 14N ratio in the Australopithecus remains to fossilized tooth samples from creatures that existed during the same era, which included both ancient herbivores and carnivores. While variable, the Australopithecus ratios were predominantly akin to those of herbivores, ultimately indicating that these human ancestors relied chiefly on a herbivorous diet.

Nonetheless, this discovery does not rule out the possibility that Australopithecus indulged in termites, which contain less 15N than the meat of large mammals. “We observe modern-day apes [fishing for termites], so why not our ancestors?” Lüdecke tells Science News’ Jake Buehler.

Ultimately, the study suggests that Australopithecus had not yet begun to embrace a carnivorous diet at that time. However, the innovative method invented by Lüdecke’s team could now be utilized to track down those human ancestors that did partake in such a diet.

“This means one can examine other hominins and attempt to perform similar measurements, striving to understand what they were consuming during their lifetimes,” asserts Bernard Wood, a paleoanthropologist at George Washington University, who did not participate in the study, informs NPR. Looking ahead, the research team intends to persist in exploring the origin of meat-eating within our ancestors and whether it instigated an evolutionary advantage.

This page was generated automatically; to view the article at its source, you can follow the link below:

https://www.smithsonianmag.com/smart-news/ape-like-human-ancestors-were-largely-vegetarian-33-million-years-ago-in-south-africa-fossil-teeth-reveal-180985873/

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website, please reach out to us