This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-02456-3

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

For months, researchers in a laboratory in Dallas, Texas, labored in secrecy, culturing grey-wolf blood cells and altering the DNA inside. The scientists then plucked nuclei from these gene-edited cells and injected them into egg cells from a home canine to type clones.

They transferred dozens of the cloned embryos into the wombs of surrogate canine, ultimately bringing into the world three animals of a kind that had by no means been seen earlier than. Two males named Romulus and Remus had been born in October 2024, and a feminine, Khaleesi, was born in January.

A number of months later, Colossal Biosciences, the Texas-based firm that produced the creatures, declared: “The first de-extinct animals are here.” Of 20 edits made to the animals’ genomes, the corporate says that 15 match sequences recognized in dire wolves (Aenocyon dirus), a large-bodied wolf species that final roamed North America throughout the ice age that ended some 11,500 years in the past.

Ancient proteins rewrite the rhino household tree — are dinosaurs subsequent?

The firm’s announcement of the pups in April, which described them as dire wolves, set off a media maelstrom. The ensuing debates over the character of the animals — and the advisability of doing such work — have opened a chasm between Colossal’s group and different scientists.

“I don’t think they de-extincted anything,” says Jeanne Loring, a stem-cell biologist on the Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. She and lots of others say that the hype surrounding Colossal’s announcement has the potential to confuse the general public about what de-extinction applied sciences can obtain.

Colossal, in the meantime, has taken an more and more combative tone in addressing criticisms, issuing fast rebuttals to researchers and conservationists who’ve publicly questioned the corporate’s work. The agency has additionally been accused of collaborating in a marketing campaign to undermine the credibility of some critics. The firm denies having performed any half on this.

Colossal stands by its claims and insists that it’s listening to dissenters and looking for recommendation from them. “We have had this attitude of running towards critics, not away,” says Ben Lamm, a expertise entrepreneur and co-founder of the corporate.

Colossal ambitions

De-extinction is an rising subject that represents the assembly level of a number of groundbreaking biotechnologies: historic genomics, cloning and genome enhancing, ostensibly within the service of conservation. The subject has roots in science fiction, with the time period seeming first to have appeared in a 1979 novel by Piers Anthony referred to as The Source of Magic. And Michael Crichton’s 1990 novel Jurassic Park — itself impressed by ancient-DNA investigations — popularized the likelihood that long-dead organisms may very well be cloned from preserved DNA.

There has by no means been good settlement on what counts as de-extinction — similar to whether or not it means cloning actual replicas of extinct species, creating proxies that fulfil their roles in ecosystems, or one thing in between. Some rely the delivery of a cloned bucardo (Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica), a kind of untamed goat, as a primary instance. The animal’s genome was transferred into goat (Capra hircus) egg cells from frozen cell samples taken from one of many final residing bucardo specimens in 2000. (The ensuing creature died inside minutes of delivery1.) But this pathway to de-extinction isn’t an choice for many species. DNA degrades over time, and with no pattern of rigorously preserved DNA, researchers must engineer the entire genome.

The creation of CRISPR–Cas9 genome enhancing in 2012 supplied another choice. Researchers can determine genetic variants that contribute to key traits of extinct animals and edit these variants into cells of residing kinfolk. They can then use that manipulated DNA to create a brand new animal by means of cloning.

Plans to convey again animals such because the passenger pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) and the woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) started to flourish. Even although there was curiosity amongst researchers and the general public, funding was a problem. “We had been unable to get really any philanthropic interest in de-extinction,” says Ben Novak, who leads a passenger-pigeon de-extinction effort on the non-profit group Revive & Restore in Sausalito, California.

But in 2021, geneticist George Church at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, who was working with Revive & Restore, caught a break. He teamed up with Lamm to launch Colossal Biosciences with US$15 million in funding, a lot of which got here from enterprise capitalists. De-extinction of the woolly mammoth could be the agency’s flagship undertaking, utilizing elephants as surrogates.

Beth Shapiro joined US agency Colossal Biosciences in 2024 to give attention to de-extinction work.Credit: Shelby Tauber/The Washington Post/Getty

Beth Shapiro, an evolutionary geneticist who’s chief scientific officer at Colossal, was initially sceptical that there was a powerful conservation argument for creating elephants that had key mammoth traits. In 2015, she informed Nature that her e-book on de-extinction, referred to as How To Clone A Mammoth, might need been extra precisely titled ‘How One Might Go About Cloning a Mammoth (Should It Become Technically Possible, And If It Were, In Fact, a Good Idea, Which It’s Probably Not)’.

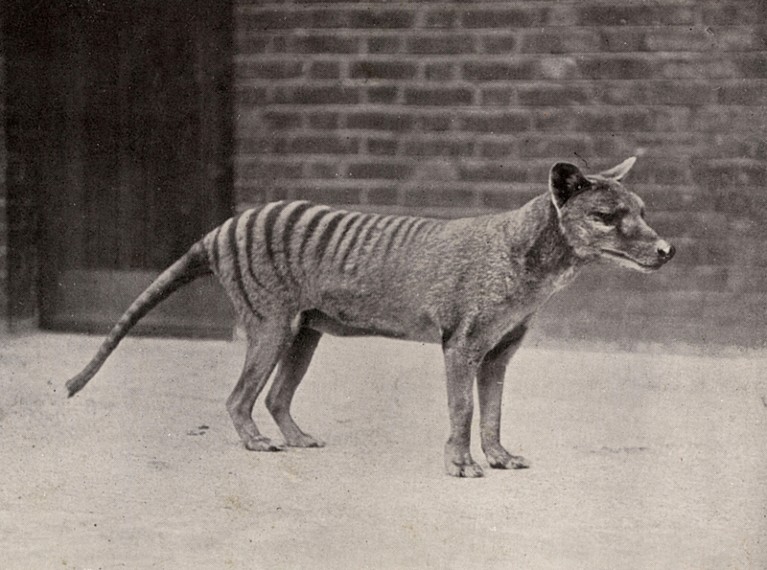

Shapiro turned down a suggestion to hitch the corporate at first, however began critically entertaining the concept when Colossal expanded its de-extinction ambitions. It started initiatives to convey again the dodo (Raphus cucullatus), which was worn out within the seventeenth century, and to revive thylacines (Thylacinus cynocephalus), the Australian marsupials which can be typically known as Tasmanian tigers and that had been hunted to extinction within the Thirties.

She was particularly occupied with seeing de-extinction applied sciences utilized to present endangered species. Shapiro joined Colossal in 2024 as its chief scientist. “This is an opportunity to scale up the impact that I have the potential to make,” she says. “Maybe it’s a mid-life crisis.”

The firm, now valued at round US$10 billion, has attracted movie star traders, together with the media character Paris Hilton and movie director Peter Jackson, alongside a handful of main scientists as employees and advisers.

Dire disagreements

The dire-wolf undertaking was completely different from lots of Colossal’s different efforts as a result of it proceeded quietly. Few folks knew in regards to the work till this 12 months, and that irked some researchers. “They didn’t invite any kind of conversation about whether or not that is a good use of funds or a good project to do,” says Novak.

Shapiro says the secrecy across the dire-wolf undertaking was designed to generate shock, and to counter public perceptions that the corporate overpromises and under-delivers. She additionally says that the corporate talked extensively to scientists, conservationists and others in regards to the undertaking and the way it ought to proceed.

The agency has not launched the complete listing of edits that it made — 20 modifications to 14 genome places. Fifteen of the modifications had been recognized in two dire-wolf genomes obtained from the stays of animals that lived 13,000 and 72,000 years in the past. The genome differs from that of the gray wolf (Canis lupus) by about 12 million DNA letters.

The dodo (Raphus cucullatus) went extinct within the seventeenth century. Colossal Biosciences goals to edit the genome of a associated pigeon species to imitate the dodo’s traits.Credit: Klaus Nigge/Nature Picture Library

Colossal says that different edits, together with modifications that led to the creatures’ white coats and contributed to their giant measurement, had been meant to copy dire-wolf traits utilizing gene variants present in gray wolves. Many scientists say that the coat color particularly was in all probability impressed extra by the animals’ look within the fantasy tv collection Game of Thrones than by actuality.

“There is no chance in hell a dire wolf is going to look like that,” says Tom Gilbert, an evolutionary geneticist on the University of Copenhagen and a scientific adviser to Colossal. He says he agrees with different scientists who’ve argued that, on the premise of what’s recognized in regards to the dire wolf’s vary, it “basically would have looked like a slightly larger coyote”. Colossal notes that the coat color relies on the invention of variants in two dire-wolf genomes that it says would have resulted in light-coloured fur.

According to an replace from Colossal in late June, Romulus and Remus weigh round 40 kilograms, round 20% heavier than an ordinary gray wolf of the identical age, and Khaleesi is about 16 kilograms. They dwell on an 800-hectare ecological protect surrounded by a 3-metre wall. Colossal plans to make extra of the animals, and to check their well being and improvement in depth. It says it is not going to launch them into the wild.

The mysterious extinction of the dire wolf

Shapiro argued in her 2015 e-book that forming a wild inhabitants is a requirement for profitable de-extinction. She nonetheless considers the dire wolves to be an instance of de-extinction, and says that creating them can have conservation advantages for wolves and different species.

Many scientists disagree. A gaggle of consultants on canids that advises the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) issued a statement in mid-April rejecting Colossal’s declare that gene-edited wolves may very well be thought of dire wolves, and even proxies for the extinct species. The assertion cites a 2016 IUCN definition for de-extinction that emphasizes that the animal should fill an ecological area of interest. The work, the group mentioned, “may demonstrate technical capabilities, but it does not contribute to conservation”. Colossal has disputed this on the social-media platform X (previously Twitter) saying that the dire-wolf undertaking “develops vital conservation technologies and provides an ideal platform for the next stage of this research”.

Novak says: “The dire wolf fits the Jurassic Park model of de-extinction beautifully.” The animals have the traits of extinct species and are, to his information, not meant for launch into the wild, he says. “It is clearly for spectacle.”

Gilbert, who was a co-author of a preprint describing the traditional dire-wolf genomes2, says he’s involved that Colossal shouldn’t be being sufficiently clear to the general public about what it has carried out. “It’s a dog with 20 edits,” he says. “If you’re putting out descriptions that are going to be so easily falsified, the risk is you do damage to science’s reputation.”

The Tasmanian tiger or thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus) was a carnivorous marsupial that when roamed Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea. The final recognized specimen died within the Thirties. Credit: Chronicle/Alamy

Lamm rejects the concept that Colossal’s messaging undermines public credibility in science, pointing to what he says was an overwhelmingly optimistic response.

Loring, who’s a part of an effort to make use of stem-cell expertise in conservation, says that she sees advantage in Colossal’s work. It has, she says, modified her views on the way to repopulate northern white rhinoceroses (Ceratotherium simum cottoni). But she worries that Colossal’s messaging overshadows these contributions. “It may create an opportunity for us to educate the public,” she says. “More often, it creates an opportunity for us to be ignored.”

To Love Dalén, a palaeogeneticist on the University of Stockholm and a scientific adviser to Colossal, the controversy is “a storm in a teacup” that detracts from Colossal’s achievement. “It makes me a little bit sad there is this huge debate and angry voices about the common name,” he says.

Dogfight

Shapiro says she was stunned and saddened by the power of reactions to Colossal’s announcement. “It was harder than I thought it would be, and the questions were getting meaner and meaner,” she says.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-025-02456-3

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us