This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://time.com/7308675/astronaut-jim-lovell-dies-obituary/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

Jim Lovell’s job by no means required him to be a poet. Once essentially the most skilled man in house flight—with two journeys within the Gemini program and two lunar missions in Apollo—Lovell, who died August 7 at age 97, went locations few others have gone and noticed issues few others had seen. But that didn’t imply there was music when he spoke.

“We’re on our way, Frank,” was the most effective he might muster in 1965 when the engines on his Titan rocket lit and he and Frank Borman took off aboard Gemini 7. “Boy, boy, boy,” he mentioned, when he and Buzz Aldrin splashed down within the Atlantic Ocean on the finish of their Gemini 12 mission in 1966. “Houston, we’ve had a problem,” he intoned when a sudden explosion crippled his Apollo 13 spacecraft in 1970, reporting the incident as if it had been nothing extra troubling than the household automotive operating out of windshield washer fluid.

None of this was Lovell’s fault. Jack Swigert, Lovell’s command module pilot aboard Apollo 13, as soon as mentioned that the very factor that certified astronauts to embark on such probably mortal missions as flights to the moon—a cool, engineer’s detachment from the scope of the expertise and the possibilities they had been taking—disqualified them from adopting the bigger, epochal view of issues. You might both go to the moon or you can recognize the going; you couldn’t do each.

And but as soon as, in my expertise, Lovell went lyrical. It was 1995, and his and my book about his Apollo 13 mission had simply been made right into a movie starring Tom Hanks and directed by Ron Howard. It was a gobsmacking expertise for me. I had spent my profession quietly toiling as a science journalist, having fun with some recognition for my work, however nothing remotely like fame. Lovell, alternatively, knew a factor or two about being celebrated, being feted, being acknowledged in eating places and sought out for interviews. And he knew, too, that fame was ephemeral—that the general public’s consideration might be a fickle and flickering factor. You are hailed after your splashdown; you might be forgotten the following yr. And so Lovell tried to supply me the advantage of his expertise, a long time after he had retired from the glittery astronaut corps.

“Remember where you’re standing when the spotlight goes off,” he instructed me on the telephone someday, “because no one’s going to help you off the stage.”

It was smart; it was great; and I held that counsel shut.

Lovell wore his fame evenly—like a unfastened garment. He was a person of the Earth—a naval officer, a father of 4, a house owner—who simply occurred to have been to house. Around the time we had been ending our guide, he was planning a trip together with his spouse, Marilyn, and was at a loss as to the place to go.

“I’ve been to Europe,” he instructed me. “I’ve been to Asia and Australia and the moon and Africa.” The moon made the checklist, but it surely wasn’t even first.

Lovell took a equally straightforward, workmanlike method to all 4 of his house missions. His Gemini 7 flight was an extended, gritty, lunch-bucket mission, with him and Borman spending 14 days aloft in a spacecraft that afforded them little extra liveable quantity than two business coach seats. There had been no spacewalks for Borman and Lovell; no dramatic dockings with the uncrewed Agena goal automobile with which different Gemini crews would apply orbital maneuvering. The males had been flying lab rats, despatched aloft to find out if human beings might survive in house for the fortnight the longest lunar missions would final.

“It was two weeks in a men’s room,” Lovell would inform me.

That mission was sufficient for Borman. He didn’t elevate his hand for any extra Gemini flights and as a substitute went straight into coaching for the Apollo program, with its spacious capsules and its glamorous journeys to the moon. Lovell couldn’t get sufficient of flying and eleven months later commanded Gemini 12, the ultimate mission of the Gemini collection, with Aldrin within the co-pilot’s seat. The males walked to their rocket with indicators on their backs. Lovell’s learn THE. Aldrin’s learn END.

It was within the Apollo program that the workaday Lovell turned the enduring Lovell. Space historians debate what essentially the most noteworthy missions of all time are and just about all of them would put Yuri Gagarin’s single orbit of the Earth in 1961—making him the primary human being in house—on the checklist. After that, most would come with Apollo 8, Apollo 11—the primary moon touchdown—and Apollo 13. Lovell flew on two of them.

Apollo 8 was a rhapsodic ending to a blood-soaked yr. It was 1968, and in January the Tet Offensive in Vietnam started. That was adopted by the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the assassination of Robert Kennedy, riots exploding in cities throughout the nation, and the violent clashes between protestors and police on the Democratic Convention in Chicago. But NASA had one thing superb and bracing and healing deliberate.

During the summer season, the house company quietly determined that earlier than the yr was out it will launch Apollo 8, with Borman, Lovell, and rookie astronaut Bill Anders aboard, into orbit across the moon.While there, the astronauts would broadcast a message residence, displaying the three.5 billion folks dwelling on the Earth what their planet seemed like from house and, extra transformatively, what the traditional, tortured floor of the moon seemed like crawling beneath the spacecraft’s window. There are a whole lot of issues that decide simply when a lunar mission will fly—the readiness of the spacecraft, the coaching of the crew, the supply of naval forces to effectuate restoration, the relative positions of the Earth and the moon when a launch is deliberate, and extra. For Apollo 8 all of these tumblers fell good and NASA decided that the optimum day for the historic orbit and broadcast residence could be Christmas Eve.

When that day arrived, nearly one in every three people on the planet was in entrance of a tv set. Borman, Lovell, and Anders performed their components gracefully—describing what they had been seeing and pondering and experiencing.

“The vast loneliness up here of the moon is awe-inspiring,” Lovell said. “It makes you realize just what you have back on Earth. The Earth from here is a grand oasis in the big vastness of space.”

The moon, Borman added, “looks rather like clouds and clouds of pumice stone.”

“The horizon here is very, very stark,” mentioned Anders. “The sky is pitch black and the … moon is very bright. And the contrast between the sky and the moon is a vivid, dark line.”

The astronauts continued their lunar travelogue for a couple of minutes extra after which—befitting the enormity of the expertise, befitting the superb and slender thread that at that second was connecting one species to 2 worlds, and most necessary befitting the season—the boys concluded their broadcast with the phrases of Genesis.

“And God called the light day and the darkness He called night,” Lovell mentioned when it was his flip to learn. “And the evening and the morning were the first day. And God said, ‘Let there be a firmament in the midst of the waters. And let it divide the waters from the waters.’”

Borman and Anders learn from the traditional verse too, after which Borman, as commander, concluded the printed. “And from the crew of Apollo 8,” he mentioned, “we close with good night, good luck, a merry Christmas, and God bless all of you, all of you on the good Earth.”

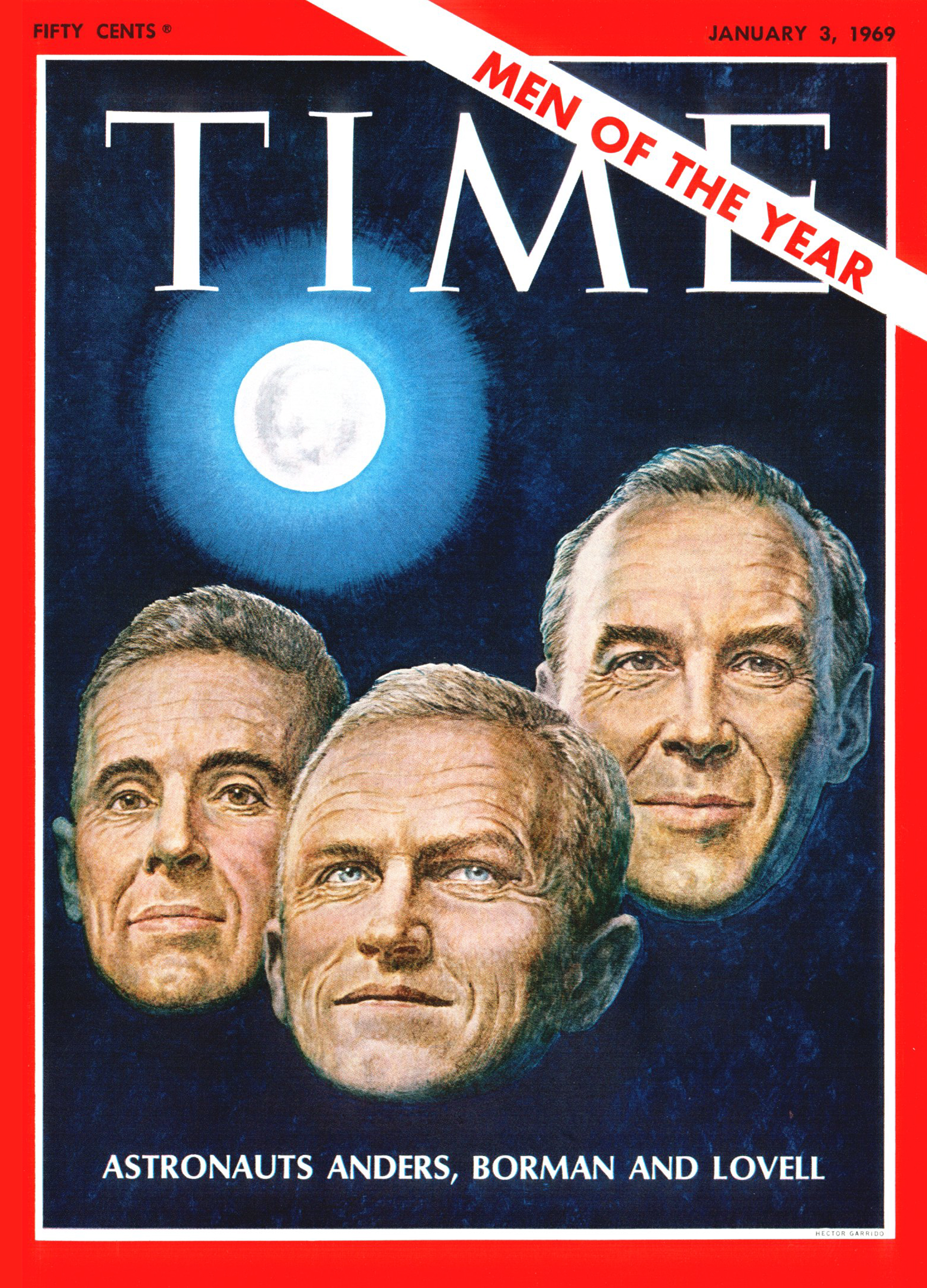

Borman, Lovell, and Anders got here again to ticker tape parades, an look earlier than Congress, a world good-will tour. TIME named them Men of the Year for 1968. A photograph Anders took of the Earth rising above the floor of the moon could be credited with sparking the environmental motion and could be hailed as one of the vital necessary photographs ever taken.

Borman and Anders wanted no extra of house and no extra of fame; each males quietly retired from the astronaut corps. History would observe that Lovell didn’t. In April 1970, he was set to fly Apollo 13, a mission that will have been NASA’s third moon touchdown. But historical past would deny Lovell the chance to get his boots soiled when an explosion in an on-board oxygen tank crippled the lunar mothership, making a touchdown not possible and turning the mission of exploration to one in all survival.

Lovell would efficiently steer his damaged ship residence, bringing himself, Swigert, and crewmate Fred Haise again alive. There could be speak—briefly—of giving the person who had twice been to the moon however had by no means been capable of stroll on it one other probability at one more mission. But Lovell knew his time in house was up. There had been too many different astronauts competing for a seat on the few Apollo missions remaining to let one man fly thrice. And Lovell couldn’t—wouldn’t—topic Marilyn, whom the exploding oxygen tank had almost widowed, to but yet another launch, yet another mission, yet another roll of the mortal cube.

Marilyn is now gone, predeceasing Jim by almost two years. Jim is now gone too. But they endure. During Apollo 8, Lovell noticed a small, fairly, triangular mountain on the fringe of the moon’s Sea of Tranquility that he named Mount Marilyn. The different astronauts took up the identify and in 2017, the International Astronomical Union, which governs official house nomenclature, broke its rule requiring options or objects named after folks to to be named posthumously, and acknowledged Mount Marilyn. My household despatched Marilyn flowers and she or he sweetly known as along with her thanks.

Over the years, I loved the hospitality of the Lovells on a handful of events, staying of their residence in Lake Forest, Illinois—as soon as with my daughters who delighted in Jim’s tour of the Chicago Museum of Science and Industry, the place Apollo 8 is on show, and the place he leaned near Anders’ earthrise image with them and defined the way it was taken. In one of many rooms within the Lovell house is a small bronzed child shoe that Lovell the explorer wore when he was simply Lovell the infant. I couldn’t assist pondering how wealthy and full it will be to have a bronzed lunar boot subsequent to it. But the foot that wore the infant shoe by no means did contact the moon.

That fickle highlight Jim warned me about has now shone its final on him. He has left the stage—and we’re left poorer for his absence.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://time.com/7308675/astronaut-jim-lovell-dies-obituary/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us