This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://defector.com/after-50-years-of-shooting-hockey-bruce-bennett-finds-an-even-tougher-challenge-birds

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

If you are inquisitive about what hockey photographers do throughout the offseason, there is not any one higher to ask than Bruce Bennett. He is the world’s most prolific hockey photographer and the top of Getty Images’ hockey imagery division. In his 50-plus-year profession, he is shot greater than 5,300 NHL video games, six Winter Olympics (with a seventh upcoming in Milan), and greater than 40 Stanley Cup Finals.

The very first thing Bennett does to get well from the grind-it-out tempo he maintains throughout the season, from coaching camps to the draft, is decompress. “No texts, no emails, no phone calls. I just want to be in my own head for a bit,” Bennett says.

But he can sit and anticipate his yard pool to freeze over for less than so lengthy earlier than his set off finger begins to twitch. That’s when he turns his focus to photographing the birds close to his residence on Long Island, a bountiful habitat for avian and aquatic wildlife that stretches from the East River to the Long Island Sound to the Atlantic Ocean.

“It gets me some fresh air and some warmth,” he says, “which I don’t get during the hockey season.”

Some mornings, Bennett rises with the solar and heads to Lido Beach, the place there is a 22-acre nature protect on one facet of the primary highway and a seaside on the opposite. “You can get American oystercatchers and terns and black skimmers,” he says. “You also get egrets on the north side, mostly by the marshland, and they’re diving for fish. There’s enough varieties to keep me busy.”

Late afternoons, he would possibly drive to Centerport or Massapequa, two locations that supply views of hovering bald eagles.

He posts his chook images on the Getty Images wire, similar to he posts his hockey photos. “When a hockey photo of mine gets used now, it’s no big deal,” he says. “But when a photo of mine of a bird swallowing a fish gets used, I’m like, ‘Ohhh, this is awesome!'”

Bennett was born in Brooklyn. His household made the well-trodden exodus to Long Island—Levittown, that fountainhead of suburbia—when he was three years outdated. He and his spouse now stay within the hamlet of Old Bethpage, situated a stiff seven-iron from Levittown, so he is virtually a local and a lifer.

Though by no means a very fluid ice skater, Bennett performed his share of road and curler hockey after college, and he grew to become enchanted with the nightly ardour play of the NHL. He grew up rooting for the Rangers, like all hockey followers on The Island did again then, watching Eddie Giacomin shield the nets and the GAG (goal-a-game) line of Hadfield-Ratelle-Gilbert torment opposing defenders. Marv Albert offered the soundtrack: “Kick save and a beauty!”

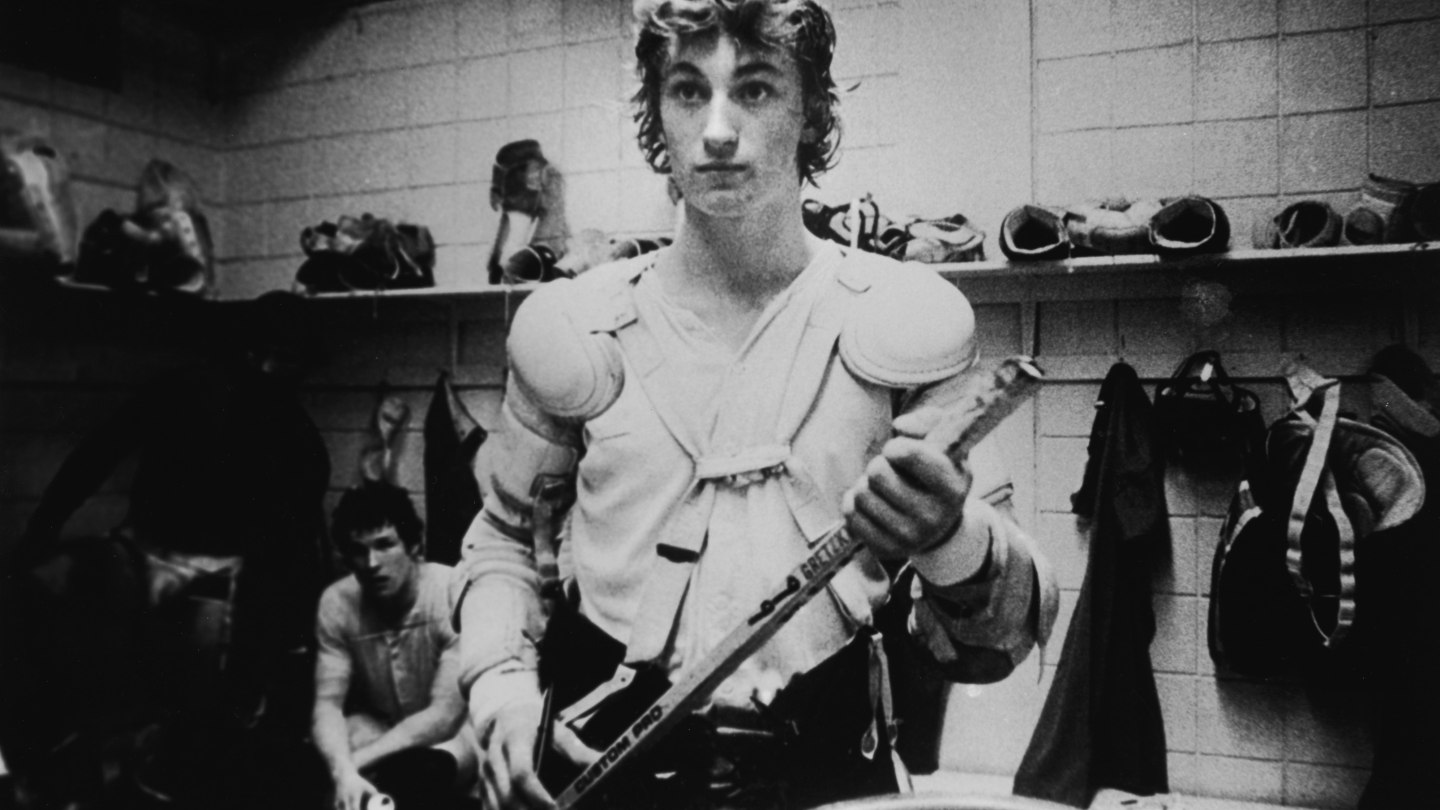

Bennett was attending W. T. Clarke High School when the Islanders joined the NHL and debuted as Long Island’s second main skilled sports activities crew. By their second season on the spanking new Nassau Coliseum, in Uniondale, he was “sneaking into the photo box” on the enviornment, and taking pictures together with his 35-millimeter Yashica digicam and 135-millimeter lens from the blue seats at Madison Square Garden. He budgeted one roll of movie per interval.

Meanwhile, he enrolled at close by C. W. Post, a part of the Long Island University system, to pursue a level in accounting. He was in his third yr when he instructed his father that he was “thinking about making a change. I’d like to become a photographer.” Bennett chuckles. “Huge mistake.

“I obtained the finger within the face as a result of he was paying for my faculty training, a whopping 1,024 bucks a semester. He was like, ‘Oh you’ll graduate along with your accounting diploma. If you wish to attempt one thing else for some time, you’ll be able to attempt one thing else for some time, however I did not spend all this cash so that you can go taking photos.'”

Armed with his degree and his parents’ support, Bennett’s leap of faith paid dividends, in part because his timing was perfect. After a quarter-century of the Original Six franchises, the NHL was furiously expanding across North America. The league had doubled in size in 1967, adding teams in Philly, L.A., Oakland, St. Louis, Pittsburgh, and Minnesota. Buffalo and Vancouver arrived in 1970, with Calgary and the Islanders coming two years later. The success of Swedish defenseman Börje Salming, signed by the Maple Leafs in 1973, cracked open the door to Europe’s vast talent base. Before the decade was out, the NHL would absorb the four surviving teams of the rival World Hockey Association, bringing with them the first true mainstream hockey star, Wayne Gretzky.

Then came the hit 1977 Paul Newman film Slap Shot, and, more importantly, the Miracle on Ice: At the 1980 Lake Placid Olympics, Team USA head coach Herb Brooks’s scrappy, undersized band of collegians rallied to upset the Soviets and then went on to win the gold medal, inspiring a wave of nationalistic fervor and attracting a generation of American-born players to the sport.

All the while, Bennett was learning how to calculate the optimal film speed and aperture to use inside dimly lit arenas, and spending hours in the darkroom. Or, as he quipped, “Getting excessive on the chemical substances—or possibly getting some poisoning from the chemical substances. Burning a gap in my dad and mom’ washer by having all my chemical substances on prime of it.”

He mailed prints to Ken McKenzie, the longtime publisher of the Montreal-based Hockey News, then known as the “Bible of Hockey.” Bennett asked McKenzie “if he wished to purchase any of my crappy images,” and recalls that McKenzie “provided three bucks a pop” and a coveted media credential.

And just like that, as the Al Arbour–helmed Islanders surpassed the Rangers and skated to a Stanley Cup four-peat, and as the players swapped their crew cuts for sideburns and mustaches, Bennett found himself ideally situated to service the growing demand for hockey pictures—traffic permitting.

“The Islanders—that was a 20-minute drive from residence,” he says, speaking in 1010 WINS, tri-state commuter tongue. “The Rangers: lower than an hour prepare journey. Then the Devils got here to New Jersey—that might be an hour-15, an hour-20. Hartford: I did that journey many instances—2:05 was the aim. Philadelphia diversified: It was like two hours–45 taking place, and just a little over two hours coming residence underneath the quilt of darkness.”

After games at the Garden, Bennett would open his leatherette camera bag, “and the scent of cigarette smoke would hit me within the face. We additionally used to have a difficulty with the stray cats who lived there. Every every now and then, one of many photographers would go, ‘Incoming cat,’ and also you’d have to fret in regards to the cat peeing in your digicam bag.”

He leaned on veteran photographers for guidance, particularly the husband-wife duo of Joe DiMaggio (insert the requisite “not that one” line here) and JoAnne Kalish. “Joe’s a personality—and I imply an actual character—and a terrific photographer,” Bennett says. “He and JoAnne, additionally a terrific photographer, confirmed me the ropes soup to nuts, taught me rather a lot in regards to the enterprise and how you can succeed, how you can cost shoppers. All the life classes that the 2 of them taught me have stayed with me my entire life.”

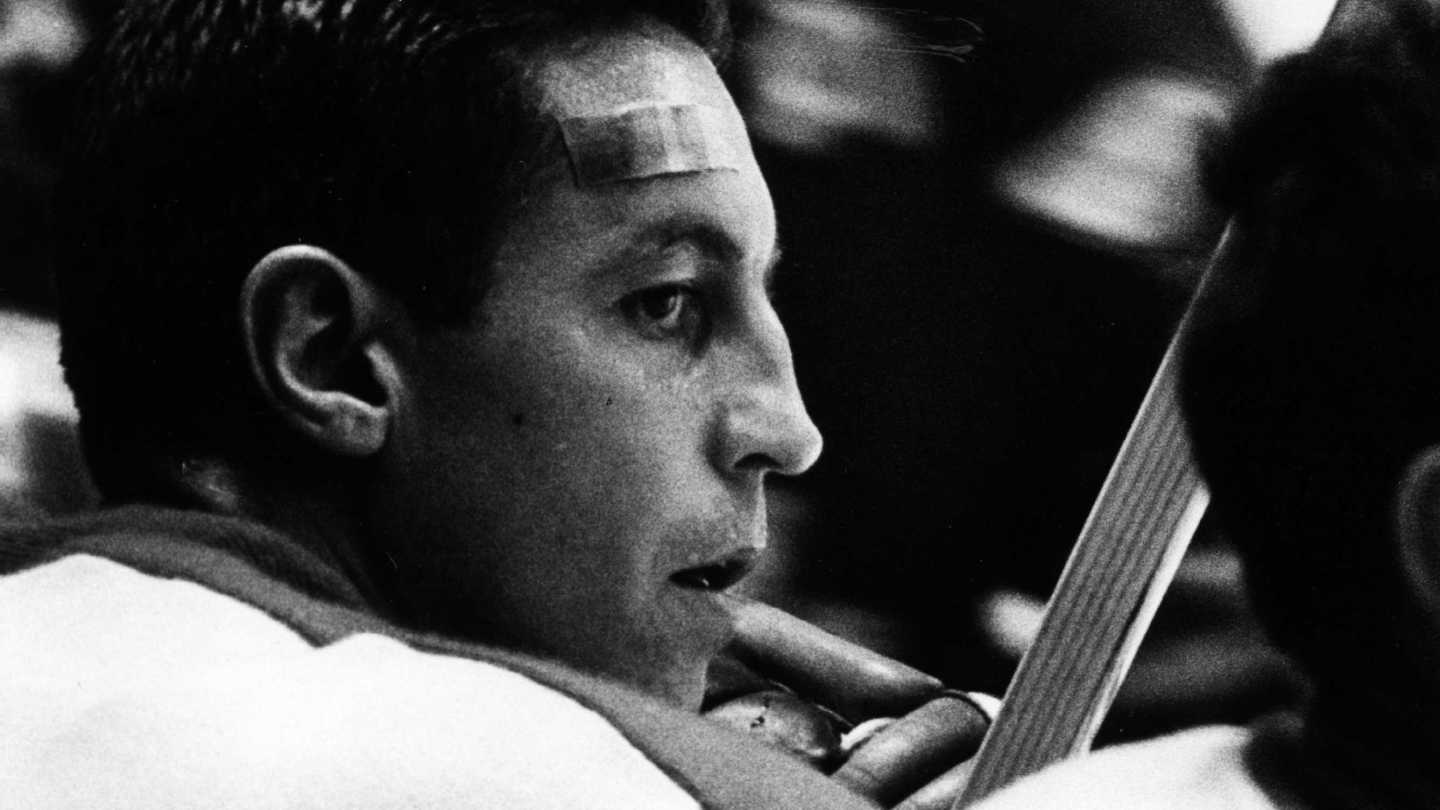

Another mentor of sorts was Montreal-based Denis Brodeur, a retired goalkeeper who transitioned to photography not long after backstopping Canada to a bronze medal at the 1956 Olympics. “Denis and I’d get collectively on the Montreal Forum, and he sometimes would come right down to see his son play, and we might hang around and speak about enterprise and pictures,” Bennett says. “He was a very gifted photographer who might anticipate the motion as a result of he’d performed the sport. Like now, I’ll shoot 20 frames a second. Back then, with the strobe lighting within the rafters, Denis would shoot one body, after which he’d have to attend 15 seconds till the strobes had been able to re-cycle and he might shoot once more. His photographs are gorgeous due to that sense of timing.” (You may have heard of Denis’s son, Hall of Fame goalie Martin Brodeur.)

Bennett threw himself into the craft, scrutinizing the work of creative shooters like Melchior DiGiacomo (who segued to tennis photography) as well as the older masters—the brothers Turofsky (Nat and Lou) in Toronto, and David Bier in Montreal. He studied hockey’s indelible images: Nat Turofsky’s shot of Toronto’s Bill Barilko’s overtime goal that clinched the 1951 Stanley Cup; Ray Lussier of the Boston Record American newspaper catching Bobby Orr fully airborne after he scored the 1970 Stanley Cup–winning goal; Brodeur’s timeless picture of Paul Henderson celebrating his Summit Series dagger with Yvan Cournoyer.

As he transitioned from shooting primarily in black-and-white to color, Bennett paced rink-side to memorize players’ tendencies: who likes to deke and who doesn’t, who prefers to shoot from the left face-off circle, which goalies tend to flop. He learned the hazards involved in covering a violent action sport: Wayward pucks struck him in the head, resulting in a dozen stitches, and in the ribs; he’s had dozens of lenses shattered.

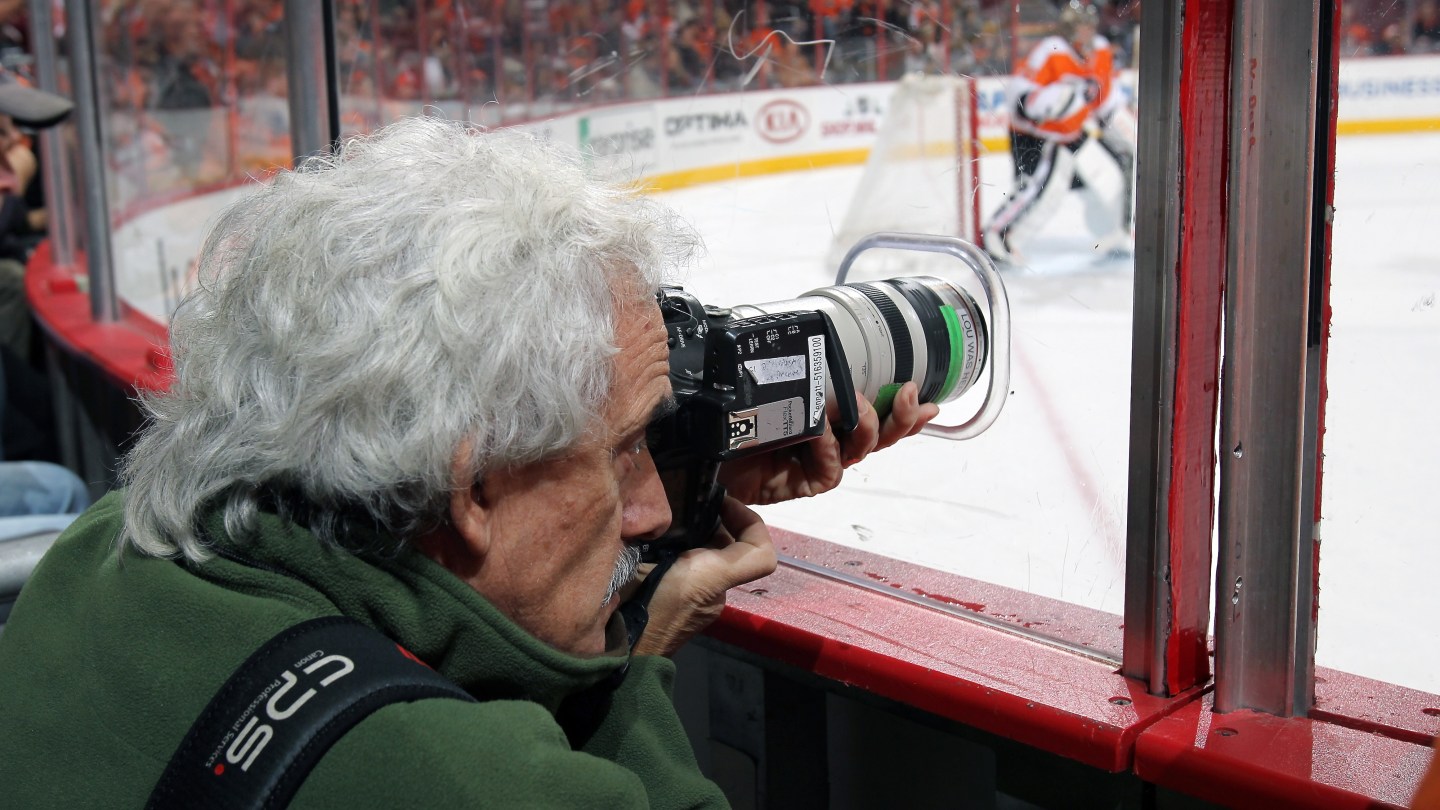

The accrued wisdom helped him overcome the nightly challenge of shooting perhaps the most difficult of the major sports to capture on film: the erratic movements of twitchy-fast athletes balanced on blades and confined to a patch of ice; uneven lighting conditions and the inconsistent glare of a sheeny white surface; the fact that photographers are generally constricted to shooting locations at the corners of the 200-foot-by-85-foot rink and must aim their lenses through a 4.5-inch-by-5.5-inch portal cut into the Plexiglass. The now-mandatory edict requiring players to don helmets and visors, while hugely beneficial for their safety, obscures their visages (and sadly eliminates those dashing images of Guy Lafleur, Ron Duguay, Bobby Nystrom and their gloriously flowing manes).

And that puck: so damn small, so difficult to track at over 90 mph, and bouncing so randomly and crookedly along the ice.

“You know, you adapt,” says Bennett, whose thick mustache wouldn’t look out of place inside a Flin Flon saloon. “You get pushed round from one place to a different. Or, you might have a distant digicam someplace within the enviornment, after which they are saying you’ll be able to’t put it there, so that you gotta go discover one other location. Or, you are sitting on a milk crate and it isn’t the proper top, so it’s a must to alter and determine how you can get to the proper top to see by way of the holes.”

Of course, for all the glory that he receives for getting “the shot” and scoring a magazine cover, there is invariably regret and disappointment. Four days before the opening ceremony of the 1980 Olympics, Bennett journeyed to Madison Square Garden to shoot a pre-tourney exhibition matchup pitting the U.S. squad against the powerhouse Soviet squad. The ensuing 10-3 rout wasn’t even as close as the score indicated, and inspired scant hope for the Americans in Lake Placid.

“I want I had shot a ton extra [at that MSG game] as a result of it was guys in U.S. and USSR uniforms,” he says. “All the gamers you are acquainted with, whether or not it is Ken Morrow or Dave Silk or [Mike] Eruzione or [Jim] Craig. The entire gang. Those have offered rather well through the years.”

He sighed. Intent on his NHL career, he hadn’t bothered to apply for press credentials to the Olympics, even though the upstate New York venue was just a day’s drive away. On his office wall hangs a full-color image of what he missed: Heinz Kluetmeier’s unforgettable photo of the American team’s jubilant celebration on the ice, which became one of Sports Illustrated‘s most iconic covers.

“Nobody predicted one thing like that,” Bennett says. “While that was taking place, I used to be sitting in my bed room in Levittown, screaming like every other child who was a hockey fan.”

He shrugged off the disappointment and moved on. He upgraded his camera equipment from Yashica to Nikon and later switched to Canon; he married his wife and had a son and a daughter. Meanwhile, the old-school style of photography practiced by the likes of his pal Denis Brodeur was being upended. Digital was replacing film, with all the technological advances and accoutrement, like high-speed cameras and faster lenses, integral motor drives and auto-focus, the ability to know immediately if you got (or missed) the shot, the capability to instantaneously transmit images around the globe.

Today, Bennett might carry six or more cameras per game, counting the remotes he places inside the pipes or high in the rafters above the goalies. “It’s a really totally different ballgame now with digital,” he says. “But you continue to need to know the gamers and how you can anticipate the motion. Even with auto-focus, at instances you are gonna choose up the flawed participant or a linesman will lower in entrance of you.”

What made Bennett so successful, and separated him from many other professional photographers, was heeding his father’s advice. The classes he took while earning his degree at C. W. Post—in accounting, marketing, finance, auditing, and law—prepared him for the cutthroat side of the business, including copyright and licensing, networking with corporate clients, and negotiating with teams and leagues.

While shooting multiple games per week, he established Bruce Bennett Studios (BBS) and signed on as team photographer for the Islanders, Rangers, Flyers, and Devils. He moved beyond North America to land lucrative global editorial and commercial projects, and jumped on the Olympic bandwagon, beginning with the 1994 Lillehammer Games. He rode another boon when hockey trading cards took off in the 1990s. “You did not have simply Parkhurst and Topps anymore,” he says, “however Fleer and Donruss and Upper Deck and Pro Set and Score. I can not even bear in mind all the cardboard corporations that got here and went.”

Bennett hired a staff of 15 editors and photographers to handle the workload. Through a bankruptcy, he acquired an archive of hockey images dating back to the early 20th century that included pioneering players Eddie Shore and Lynn Patrick, as well as a cache of some 3,000 pictures from Russia. He purchased the collections of notable hockey shooters Chuck Solomon and Rich Pilling, as well as Robert Shaver’s photos chronicling the early years of the Buffalo Sabres and the French Connection line of Rick Martin–Gilbert Perreault–René Robert.

“A variety of photographers had been equal to me or higher than I used to be, as shooters,” he says. “I used to be in a position to make the offers to promote my images and make a buck. That’s a part of the talents that you simply’re not taught within the picture colleges. You discover that plenty of artistic individuals haven’t got that gene.”

In 2004, Bennett sold BBS to Getty Images for an undisclosed sum. The company’s catalog of approximately 2 million hockey images was shipped to a climate-controlled facility in Los Angeles for storage, preservation, and digitization. The deal included Bennett staying on to head Getty’s hockey photography branch while also maintaining a steady shooting schedule during the season. These days, he raves about the newly opened UBS Arena, near Belmont Park, where the Islanders have played since 2021, calling it a significant upgrade from their former homes, Brooklyn’s Barclays Center and the Nassau Coliseum.

“It could have been a dump,” Bennett, a Long Island loyalist to the bitter end, says of the Coliseum, “however it was our dump.”

The upcoming season offers an intriguing wrinkle with the 2026 Milan-Cortina Olympics, with NHL players participating on their respective national teams for the first time since the 2014 Games. Using photos and schematics of the two ice hockey venues in Milan, Bennett has already begun plotting shooting locations and remote camera placement with Getty Images’ tech crew.

“It’s a problem,” says Bennett, who’s shot 259 Olympic contests, with a personal record of 41 games in Beijing in 2022. “Photographers at that degree—those who’re despatched to the Olympics by their shops—they do not fail. So, it’s a must to be in the proper headspace to do your job, it’s a must to be bodily able to do it, and I’m. We’ll have a plan for myself and the opposite Getty Images photographers—the place they are going to be, the place the distant cameras are going to be arrange—and depend on our expertise to make it possible for no necessary historic second is missed.”

Bennett admits that he struggled at times during the 2018 Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea. “I took on an excessive amount of,” he says. “I wasn’t sensible about it, and I realized from that have. Physically I obtained higher after that, and I’m smarter about how I do issues.

“Although it still seems like, when the Stanley Cup Final comes around, I’m the guy carrying the most shit, so maybe I didn’t learn all that much.”

Bennett jokes that the perfect approach for him to conclude his profession “would be to get hit by a Zamboni at center ice. You know: red line, blue line, Bruce line.” After cresting 70 final spring, and with grandchildren within the combine, he acknowledges that he’ll most likely start scaling again his schedule earlier than later. “It’s hard to think ahead,” he says. “I’m not a big planner that way. When it’s time, it’s time. You don’t want to leave too early and sit and stare at the walls. Right now I could do a game every other night during the season and not even blink twice.”

He envisions spending his retirement nonetheless steeped in pictures, with time sufficient for backburner initiatives, together with publishing follow-up volumes to his prompt basic ebook from a decade in the past, Hockey’s Greatest Photos: The Bruce Bennett Collection (Juniper Publishing). “I’m thinking of maybe a goaltenders book, a forwards book, a defensive book, USA hockey players, lot of options,” he says.

Another attainable “retirement thing” is a ebook of his avian pictures. During the primary yr of COVID-19, when Bennett began experimenting with taking pictures birds on Long Island, he tried adapting the skillset and the digicam settings he employed for taking pictures hockey, however discovered that these did not fairly work.

“The biggest difference from hockey to bird photography was the focusing point,” he says. “Typically in hockey we chose ‘one dot’ for focus. It’s the fastest way to get a lens to lock in. That was stuck in my brain when I started with birds. Try putting that ‘one dot’ on a bird like a falcon, at 240 miles per hour, and your rate of success is pretty limited.”

Bennett “rethought the focus pattern and utilized more of the in-camera capabilities in the Canon line, including special ‘animal’ focusing algorithms,” he says. He watched YouTube tutorials and studied what different chook photographers had been doing. He downloaded apps to assist him acknowledge the numerous species he was encountering; he prefers Merlin and eBird, instruments produced by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology that allow customers to tell apart birds through pictures and sound and to pinpoint places the place birds have been noticed. He admits to wishing that the birds wore “helmets with numbers on them so I could identify them. There are times you go, ‘Great shot, who is that?'”

The outcomes have proved gratifying. “It’s like, oh my God, I’ve found something so gorgeous to photograph,” he says. “It provides me with a challenge equal to or greater than photographing hockey players.”

When Bennett goes “hunting” for chook images on Long Island, he gravitates primarily to Lido Beach, Oceanside, Centerport and Massapequa. “I missed the chance for snowy owls at Jones Beach as I couldn’t put the time in, and there is a place near Calverton Cemetery that’s been on my list for a couple of years,” he says. “But it’s always an issue when people talk about what they saw somewhere … yesterday. Today and tomorrow are new days and usually the inhabitants vary greatly day-to-day. At least hockey players always come back the next game.”

He’s drawn towards taking pictures the bigger varieties—or, as he places it, “I am a big bird guy. Sparrows and other little ones don’t interest me. The blue jays and cardinals that populate my backyard are beautiful, but give me an egret, an eagle, a hawk, or a blue heron any day.”

Perhaps his single favourite is the roseate spoonbill. “There was one, just one, on Long Island last year, and people lost their minds,” he says. “They are in the flamingo family with a gorgeous shade of pink and are kind of goofy-looking.”

Once, on a visit to a protect in Florida, Bennett espied a lone roseate spoonbill up on a pole. He leaned into one other key lesson gleaned from a half-century of taking pictures hockey—endurance—and “just stood there, ready for it, focused and focusing, and saying, ‘I’m just gonna have to wait it out.'”

When the chook took off, he captured it in full flight. “Sometimes the bird wins and sometimes you win,” he says.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://defector.com/after-50-years-of-shooting-hockey-bruce-bennett-finds-an-even-tougher-challenge-birds

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us