This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://english.elpais.com/culture/2025-09-05/sebastiao-salgados-final-thoughts-if-we-lived-thousands-of-years-we-would-think-differently-we-would-understand-the-mountains.html

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

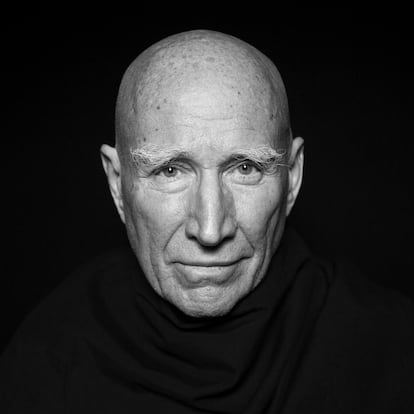

“I’m not the best photographer in the world, I’m the hardest-working,” Sebastião Salgado informed me in a gentle voice. His nearly excellent Spanish was enhanced by the calm, melodious cadence of his Portuguese: “A photographer belongs to a breed apart: I’m not an artist; a journalist reconstructs reality, but a photographer doesn’t. I have the privilege of looking, nothing more.”

On February 5, 2025, we met on the Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City, the place he introduced Amazônia, the final large-format exhibition he opened throughout his lifetime.

I labored on this profile with out suspecting that I must modify the verb tenses for the saddest of causes: the photographer died on May 23, 2025.

A person of extremes, Salgado ignored routine phrases and knew nothing of indifference. One of his recurring phrases was “colossal.” He appreciated to quote astonishing statistics with the authority of somebody who, in a single day, noticed 10,000 folks die in Rwanda. He was captivated by the extremes of the human situation: hell and paradise, fall and redemption.

Salgado was born within the small city of Aimorés, Minas Gerais, in 1944. Trained as an economist, he left dictatorship-era Brazil in 1968 and labored in London and Paris. In 1973, he left his place on the International Coffee Organization to commit himself to images. It was a late awakening. He was about to show 30 when his spouse, Lélia Wanick, lent him a digital camera. These have been the times of analog images. The foremost revelation got here not within the darkroom, however within the thoughts: photos expressed actuality higher than numbers.

As quickly as we greeted one another, Salgado spoke of the encircling surroundings in his typical superlative model: “It’s the best museum in the world!” He then talked about a brand new facet of the exhibition: the pictures for the blind, that are interpreted by contact. I attempted deciphering silhouettes with my fingers, however to no avail. “You just need to be blind,” he commented sarcastically.

Although we have been a good distance from the jungle, the creator of Amazônia was sporting his typical work garments: saggy, waterproof trousers with giant pockets on the edges, rubber-soled footwear, and a mountaineering vest. About to show 81, he walked across the exhibition with energetic ease. He appeared in fine condition and spoke enthusiastically about future initiatives. But there’s no strategy to anticipate the roulette wheel of destiny. Some time in the past, he had contracted malaria. The after-effects of his travels have been in his blood; the menace appeared underneath management, however it will definitely led to leukemia.

From the age of 29 till he was 81, Salgado walked sufficient to circumnavigate the globe a number of occasions over. He lived to chase frames. The documentary The Salt of the Earth (2014), directed by Wim Wenders and Juliano Ribeiro Salgado, Sebastião’s son, captured his ardour for shifting, crawling, and creeping in pursuit of a shot. In one scene, he rolls on a pebble seaside in order that the walruses he intends to {photograph} received’t discover his presence.

Salgado’s blue eyes conveyed the weird calm of a restful traveler. His closest buddies knew he disliked criticism, particularly from colleagues, however in public he reacted with the poise of a Zen monk, worthy of his polished cranium, merely saying, “My angel and your angel don’t meet.”

Salgado settled in Paris, the place he might disconnect from the turbulence he captured in his images. Few settings have the visible attraction of the “City of Light”; nonetheless, his Parisian territory consisted of two areas: his laboratory and his dwelling. “I don’t know of any photos of Sebastião in Paris,” says his shut pal Graciela Iturbide. “He likes living there, but his mind is elsewhere.”

During the interview, Salgado appeared to be on no schedule in any respect. He had woken up at 5:00 a.m., however he didn’t simply reply the query at hand; he anticipated the following 5 with the eloquence of somebody who has woven a discourse for years. At the tip of the interview, he would remark: “I was exhausted, but I rested by talking.”

I believed it was acceptable to begin by speaking in regards to the walks along with his father: his faculty of imaginative and prescient. “My photographs are usually set in nature. The sky is a very important part of my photography because I was born on a ranch where the light is the most fantastic thing you can imagine. In October, when the clouds began to form, I would go with my dad to the countryside. He didn’t like riding horses; he preferred to walk for three or four hours; we would climb to the highest point on the ranch and watch the clouds and the sun passing through them. That remains with me.”

Nature will be idealized to the purpose of distortion. When Mario Vargas Llosa was researching the Amazon to jot down The Green House, he found how simple it was to fall into exaggeration when confronted with an immense panorama: “Butterflies bigger than eagles, trees that were cannibals, aquatic snakes longer than a railroad,” he recounted in The Secret Story of a Novel.

Werner Herzog sought a extra dramatic strategy. In his movie Fitzcarraldo, he informed the story of a person decided to maneuver a ship by way of the Peruvian Amazon. Defeated by the weather, the filmmaker printed a filming diary with the long-lasting title: Conquest of the Useless. It’s not simple to dominate an surroundings that has resisted predators and distorting interpretations for millennia.

In his collection on social themes (Workers, Other Americas, Sahel, and even Genesis, devoted to nature), Salgado powerfully expressed actuality; his images of the Amazon explored one thing intimate: the key lifetime of vegetation.

Certain artists undertake a “late style” late in life. This is the case with the Beethoven of string quartets, the Goya of the Black Paintings, or the Thomas Mann of Doktor Faustus. Salgado belonged to that lineage. His transition to a unique manner of seeing trusted the shift from the social to the ecological, but in addition on a technical transformation, from analog to digital. “All my life I’ve worked with Tri-X,” he stated, referring to the world’s best-selling black-and-white movie: “I knew it like the lines on my hand. It’s the same with digital: I know my lights.”

The pitfalls of fame

Salgado was arguably probably the most well-known photographer on the planet, but he obtained blended opinions. For half a century, he documented injustice and gave away a lot of his work; nonetheless, for some, he was a celebrity who promoted an “esthetic of misery,” monopolized museums, and printed outsized books.

The plain, affable tone wherein he addressed the Mexican technicians engaged on his exhibition, which earned him the belief of 1000’s of individuals, couldn’t have been extra modest, however probably the most harsh feedback have been directed not at him as an individual, however at his manner of seeing issues. Ingrid Sischy accused him in The New Yorker of the “beautification of tragedy,” and Jean-François Chevrier in Le Monde of working towards “sentimental voyeurism.” There was no scarcity of responses in protection of the Brazilian. In his typical aphoristic model, Eduardo Galeano wrote: “Charity, vertical, humiliates. Solidarity, horizontal, helps. Salgado photographs from within, in solidarity.” Without the aspect of magnificence, quite a few photos can be forgotten. Esthetics generates empathy. Gilberto Owen expressed this enigma in an aphorism: “The heart. I used it with my eyes.”

According to Salgado, those that criticize “photography of misery” don’t strategy the privileged witnesses in the identical manner: “Irving Penn, Richard Avedon, Annie Leibovitz, the great American photographers who portrayed the rich in their country and who have worked on the great fashion shows, do not receive criticism because it is assumed that beauty belongs to the rich; but if you portray the beauty of the poor, there is criticism because it is assumed that someone poor has to be ugly and must live in an ugly place, but no: they live on our planet, which has a wonderful sky and incredible mountains; I must show that in the midst of their material poverty.”

“Salgado’s problem is success,” feedback Argentine photographer Dani Yako: “His appropriation of themes isn’t just his; all photographers take over the lives of others. At first, he didn’t think about being exhibited; he worked for newspapers, but galleries framed his work differently, and sometimes that leads to misunderstandings. What’s important is his work.”

Controversy not often leaves a public determine unaffected. On January 17, 2025, The Guardian printed an article about Salgado’s ecological images, Trouble in Paradise for Sebastião Salgado’s Amazônia. The article reported that anthropologist João Paulo Barreto, a member of the Tukana Indigenous neighborhood, visited the Amazônia exhibition in Barcelona and left after quarter-hour, shocked by the show of nudity: “Would Europeans dare to exhibit the bodies of their mothers and daughters like that?” he requested. According to Barreto, Salgado seen Indigenous folks with a colonial angle.

Shortly after, the article was refuted in a letter to The Guardian by Beto Vargas, an Indigenous chief of the Marubo group. Vargas emphasised the significance of portraying the inhabitants of the deepest reaches of the Amazon; the truth that they seem nude just isn’t an artifice; that is how they reside and shouldn’t be Westernized to be revered. Vargas witnessed the periods wherein Indigenous folks themselves mentioned learn how to be portrayed and commented that, because of Salgado, Brazil’s Supreme Court enacted the ADPF-70 regulation to ensure the medical care denied to Indigenous folks in the course of the pandemic by the Bolsonaro authorities.

The Guardian report arose from a coincidence: Salgado’s exhibition was introduced in Barcelona concurrently one other exhibition wherein Barreto himself participated: Amazonias. El futuro ancestral (Amazonia. The Ancestral Future).

Humans love dichotomies: crimson wine or white wine, the seaside or the mountains, Barça or Real Madrid. The Guardian created a pointless rivalry between two distinctive initiatives.

I had the chance to interview the curator of The Ancestral Future, Claudi Carreras, an incredible connoisseur of Latin American tradition. “I’m screwed,” he stated upon welcoming me on the Center for Contemporary Culture in Barcelona. For eight months, he traveled 6,900 kilometers (4,290 miles) by river to document a pure world that features not solely jungles but in addition deserts and glaciers, the place almost 300 languages coexist and the place popular culture combines vernacular devices with electrical guitars.

He, too, fell sufferer to the stress that arises between those that defend their roots and people who come from distant. At first, Barreto refused to satisfy him: “I don’t talk to white people,” he informed him in Manaus. However, after assembly along with his elders, the Tukano anthropologist reconsidered. Carrera supplied him the place of one of many 11 curators of The Ancestral Future, and Barreto contributed probably the most ethnographic and traditionalist part of the exhibition.

For his half, Salgado recorded the peaceable sprouting of vegetation as solely a conflict correspondent might. Some revelations arrive by way of distinction.

The fact is, there’s nobody strategy to strategy the world’s nice nursery. Amazônia and The Ancestral Future have been complementary efforts.

The trial of colleagues

I spoke with a number of photographers about Salgado and determined to maintain their statements within the current tense to be devoted to how they seen a residing colleague.

Pablo Ortiz Monasterio, founding father of the journal Luna Córnea, was dazzled by the Other Americas undertaking. This poetic imaginative and prescient of a devastated actuality appeared alien to him, freed from any try to beautify the horror: “The problem lies with advanced capitalism, which causes conflicts and then commercializes them; this controversy not only affects him, but anyone who touches on these issues. His style is unique; Kodak asked you to turn your back to the sun; he seeks the light; he is so virtuous that it is overwhelming.”

If these pictures didn’t seduce us, they wouldn’t have an effect on us both. In this sense, magnificence offers an ethical argument.

Ortiz Monasterio suggested Salgado on his journey to Munerachi, in Mexico’s Sierra Tarahumara: “He shot 20 or 25 rolls of film a day, sending them via Federal Express in special envelopes to protect them from X-rays. It’s mind-blowing to see him working under such great pressure; he traveled with a stack of 200 contacts that he reviewed at night. When he was at the Magnum agency, he earned more than all the other photographers; that provokes admiration, but also jealousy and envy.”

For his half, Dani Yako informed me over a video name: “Everything about Salgado is grandiose, from the skies to the mass movements. Even in his supposedly intimate photographs, he’s as exuberant as [Gabriel] García Márquez. He achieves something almost unreal; you think it can’t exist: that’s the merit of his quest.”

A easy man can have uncomplicated calls for: “When he invited me to his house for dinner, he cooked,” Yako says. “He doesn’t behave like a star. He still lives in the same place as always, but there’s obviously a distance; his life is different: while we were eating, his lab technician brought him photos he had to send to The New York Times aboard the Concorde.”

Salgado’s finest pal in Mexico is Graciela Iturbide. I visited her at her dwelling within the Niño Jesús neighborhood of Mexico City. A younger man stopped me on the highway and requested the place I used to be going. I discussed the photographer’s identify, and he supplied me a experience, proud to be the neighbor of a nationwide determine.

Iturbide was recovering from a fracture, however she maintained the serene composure which she appears to attract photos to her with out looking for them out. She had solely been out on the road as soon as, to attend the inauguration of Amazônia. She met Salgado in 1980, when he sported an extended blond beard and hippie mane: “I have a photo of him from that time: gorgeous,” Iturbide remembers. “His mind and heart were more pristine then, open to surprises. I got him a flash so he could photograph the Basilica of Guadalupe. After that trip, he stayed at my house several times and I let him use my bedroom. Mexico was his gateway to the Other Americas.”

Iturbide and Salgado photographed collectively in Villa de Guadalupe, Xochimilco, and Veracruz. For each photograph of hers, he took 100: “He has amazing discipline; he never stops. I’m more of a choosy type. I don’t like rushing; I prefer photos that lead to a development in the lab.”

Iturbide additionally noticed a really totally different photographer in motion, Henri Cartier-Bresson: “Henri waited until he found the opportunity; I wait for the moment too. On the other hand, Sebastião doesn’t stop, which is why it was good for him to switch from analog to digital; he likes to do things quickly, but he develops photos as if they were analog, don’t ask me how. I exchanged 10 of my photos with others of his, but his are large format and I have nowhere to put them. The ones I like the most are those of Serra Pelada. I love being his friend after so many years; there are photographers who stop talking to each other; I can give you examples, but not for the interview.”

The synchronicity between the photographers reached a second of sunshine and shadow on May 23: Iturbide was honored with the Princess of Asturias Award, the identical day Salgado died.

Nature as remedy

Robert Capa died after stepping on a mine in Vietnam, fulfilling certainly one of his axioms: “If the photo doesn’t work, it’s because you weren’t close enough.” His colleague from Minas Gerais adopted the phrase and lined the horror with unprecedented proximity. Far from sensationalism, Salgado sought the dignity of these struggling and used esthetics as a way of protest.

However, recording disasters took a heavy toll. Toward the tip of the Nineties, after witnessing burning oil wells within the Kuwaiti desert and following displaced folks in Africa, he fell sick with an unprecedented sickness, introduced on by what he had seen.

It was simply then that his father left him the household farm. “I was born in Minas Gerais; our baroque was born there, and my photography is very baroque. I started photography very late, but the impulse came from afar, as did my ideological heritage, which came from a poor, underdeveloped country. I have done social photography almost all my life and began doing environmental photography in 2004, when I understood that I had to return to the planet. I understood the evolution of society when Gorbachev appeared and transformed the Soviet Union; he was just one man, but behind him were thousands of people who needed that; if it hadn’t been him, it would have been someone else.

“Evolution has a collective logic. I worked in Mexico in the 1980s when no one thought about the environment or the protection of nature. When I first came to Mexico City, I found a mineral city; today it’s a green city; if you look closely, all the trees are young, 20 or 25 years old. My photography follows the changes of the human species. I worked a lot in Africa, I was involved in the genocide in Rwanda, and I covered the reorganization of the human family in the series Exodus. What I saw in Rwanda was the most terrible thing I’ve ever seen; I became psychologically and physically ill. I went to see a doctor because I felt so bad, and he told me: ‘Sebastião, you’re not sick, you’re dying. If you continue like this, you won’t be able to go on, because your body has entered a state of destruction.’”

Brazilian essayist Ricardo Viel, who works for the José Saramago Foundation in Lisbon, attended a lecture by Salgado about 15 years ago: “He had trouble remembering things,” he informed me on the Casa dos Picos, which homes the Portuguese novelist’s legacy. “When I talked to him, he seemed to have lost his memory and frequently went to Lélia to ask her for clarifications.”

In our conversation, Salgado returned to that critical moment: “I went to Brazil, we rented a little house on the beach, and I decided to abandon photography; I was ashamed of being part of such a predatory, brutal species.”

The family farm, which had been a productive orchard, was completely eroded. Salgado decided to restore it. For every photo he had taken, he planted a tree. By 2014, the land that had been barren in 2001 had flourished in an extraordinary way.

As the countryside turned green, he healed: “I saw the trees emerge and the insects return, and with the insects, the birds, and then the mammals. I was healed, regained great hope, and decided to return to photography.”

No colleague had ever taken so many helicopters, canoes, horses, mules, or small planes. “How many roads must a man walk down before you call him a man?” Bob Dylan wondered. In the case of Salgado, who traveled to more than 100 countries, one might ask if there was any road he missed.

When he returned to his craft, he did so in an epic way. Between 2004 and 2012, he embarked on 32 trips. The result was Genesis. “I wanted to see my planet, what was pristine about it, what hadn’t been destroyed. I went to Washington, to Conservation International, and discovered that 47% of the planet was as it was at the moment of genesis — not the habitable parts, but the highest, wettest, coldest, most desert-like lands — and off I went. For eight years, I gave myself the greatest gift a person can give themselves. But the most important journey was an inner one. I understood that I am nature. When I was in northern Alaska, I had a very fat Inuit guide, shorter than me, who couldn’t climb the mountains. We landed on very narrow, short airstrips, and the plane couldn’t carry much weight. I preferred to remain alone, without the Inuit. In the mountains, accompanied by plants and minerals, I understood that I was one among others. There I regained hope, not in my species, which doesn’t deserve to be on this planet, but in a planet that is rebuilding itself.”

For decades, Salgado was a ground-level witness. In the Amazon, he had to take off to capture vast spaces: “There are no special planes to photograph the forest from above, nor are there drones because there are no bases to fly them. The largest mountain range in Brazil is in the Amazon, but there are no photographs of it because there is no access. I had to turn to the army, the only institution with representation in that territory, with 23 barracks. They agreed to let me travel in their planes, with the doors open for photography. These weren’t missions [put on] for me; I joined the ones they had [planned] and contributed fuel (45,000 liters); that’s how I was able to photograph a region of almost 500 kilometers, a group of islands formed during the last period of the Ice Ages.”

This memory ignited his enthusiasm for the unprecedented: “I was able to photograph aerial rivers; it’s a new scientific concept, one that’s been talked about for about eight or 10 years. The evaporation from the rivers and lakes of the Amazon is immense; it’s the only area on the planet with its own evaporation that guarantees rainfall. This forms colossal clouds. The volume of water that emerges into the air is greater than the water that the Amazon River discharges into the Atlantic Ocean.”

The second journey: memory

What did Salgado dream about? “After a heavy dinner, I have nightmares. I go back to the days of analog photography, dreaming that I don’t have film and I’m shooting with nothing in the camera, or that the film was exposed to light and everything was blurred.” At night, all the photos he had taken didn’t calm his subconscious. During the day, he transformed them into memories.

For John Berger, the antecedent of photography is not drawing or engraving, but memory. The image is a temporary certificate.

On the verge of turning 81, Salgado reflected on his age. Unbeknown to him, we were on the threshold, and his words took on dramatic weight with his death: “We live very short lives, 80, 90 years. If we lived thousands of years, we would think differently: we would understand the mountains. But we pass through the world very quickly; it is necessary to make an effort to capture nature. I remember one day I was in the Amazon with Lélia, and a military helicopter flew over; we took off with the doors open in that Black Hawk, and I was busy photographing until I looked away and saw Lélia crying. I asked her what was wrong, and she said, ‘It’s beauty.’ Paradise was all around.”

How to choose the moments of hell or paradise? “Photography is living within a phenomenon that you portray from the beginning, waiting for it to reach its climax. You keep photographing until it loses intensity and disappears. Next Saturday, I’ll be 81, and I can’t start a long project anymore; I’m traveling within my life, returning to my contact sheets. I have more than 600,000 postcard-sized photographs, and I love the second trip of reviewing them. The other day I was editing some photographs I took in the mountains of Ecuador in 1976 or 1977. I got hepatitis there, but I didn’t have the money to return to Paris, and I worked while sick. When I returned to those photographs, I got sick again! I photograph with the same intensity as I edit; I smell the smell of pork rinds in the mountains of Ecuador! In the photos of Mexico, I remember the tequilas I drank.” Salgado looked up, remembering something distant, and John Berger was right again: photography belongs to memory.

With celebratory enthusiasm, Victor Hugo wrote to the photographer Edmond Bacot: “I congratulate the Sun for having a collaborator like you.” He would have congratulated Salgado for his clouds.

During the conversation, I mentioned Mário de Andrade’s novel Macunaíma, which is set in the Amazon and ironically depicts a region “full of vermin and poor health.” To avoid the danger of working, the protagonist repeats an existential motto: “Ah! Just so lazy.”

The most active of photographers admired the story starring a slacker. After our talk, he asked if we could look at a photo of the Macunaíma landscape. “There it is,” he said, pointing at the river with the discretion with which one points at a person so as not to offend them.

The death of Sebastião Salgado, which occurred shortly after our meeting, gave testamentary value to one of his phrases: “We pass through the world very quickly.”

His legacy, made of moments, is already inscribed in memory.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get extra English-language information protection from EL PAÍS USA Edition

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://english.elpais.com/culture/2025-09-05/sebastiao-salgados-final-thoughts-if-we-lived-thousands-of-years-we-would-think-differently-we-would-understand-the-mountains.html

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us