This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://gayety.com/queer-lens-photography-history

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

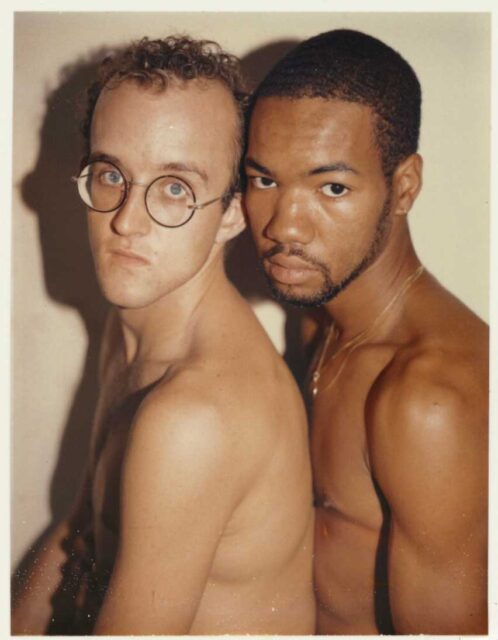

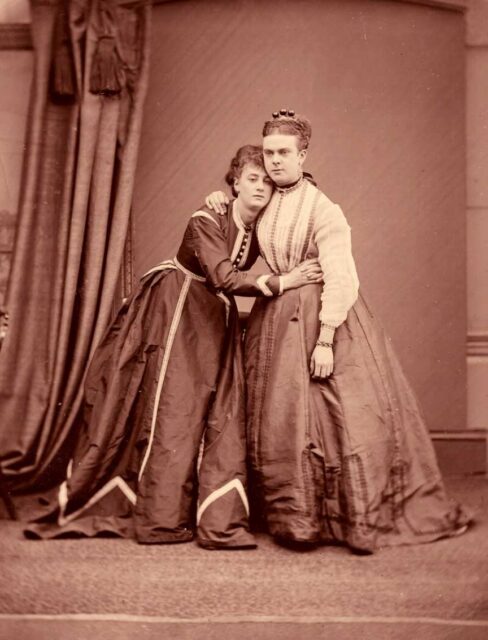

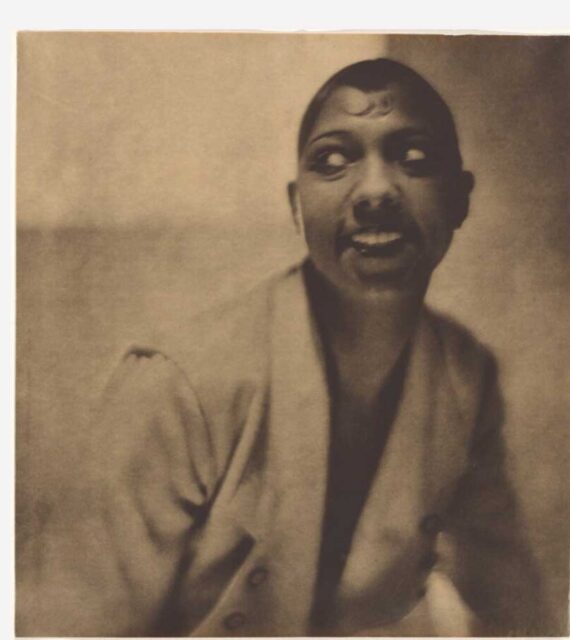

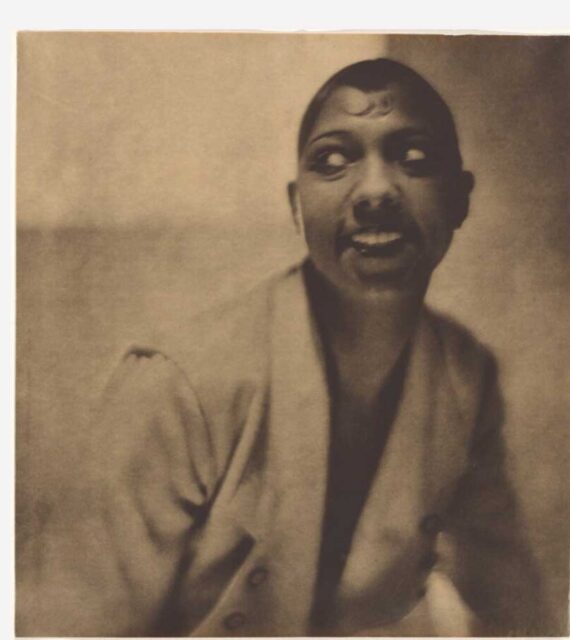

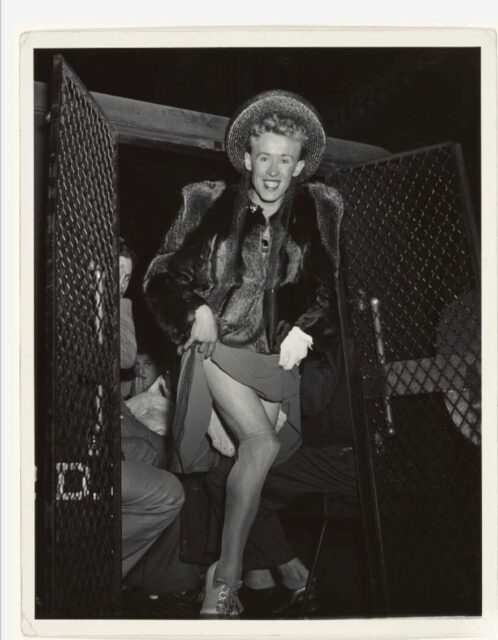

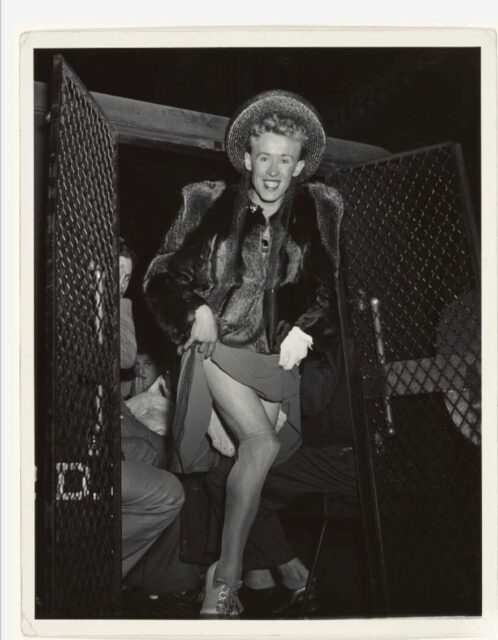

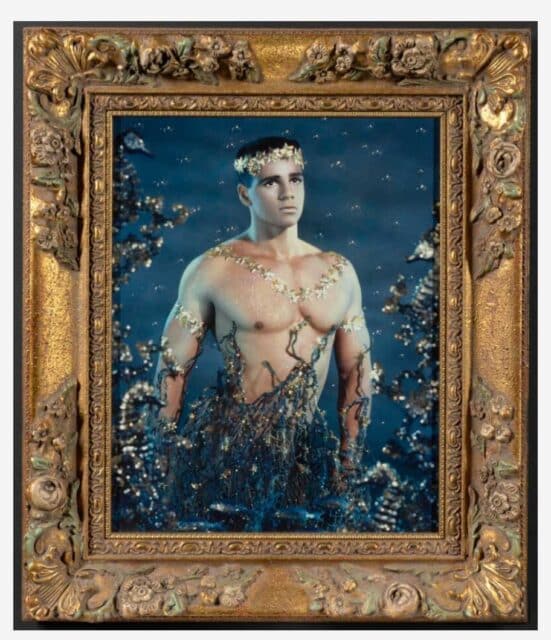

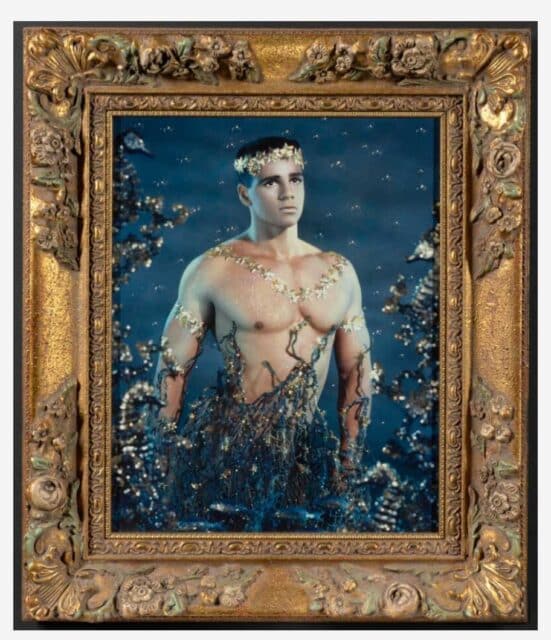

Photography has all the time been greater than a technique to freeze a second in time. Since the nineteenth century, the digital camera has captured intimacy, defiance, and the numerous methods queer folks have expressed identification. Through the Queer Lens: A History of Photography revisits this visible file, unearthing how images grew to become proof of each survival and celebration for LGBTQ+ communities.

A Medium of Visibility

From its earliest days, images supplied one thing different artwork types couldn’t: immediacy. A portrait may doc forbidden relationships or sign queer identification with refined gestures. These photographs had been typically exchanged in personal, offering a type of affirmation in a world that didn’t permit open recognition.

Even during times of censorship and erasure, images remained a lifeline. Many had been hidden, destroyed, or suppressed, but sufficient survived to testify to the resilience of queer expression.

Reclaiming “Queer”

The exhibition additionally addresses the difficult historical past of the phrase “queer.” For a long time, it was used as a slur. Today, many have reclaimed it as a time period of empowerment and inclusivity. Wall texts inside the present clarify this shift, framing “queer” not as an insult however as a broad, gender-neutral umbrella that acknowledges folks typically neglected by narrower identifiers.

The curators emphasize that the time period is used deliberately and respectfully, honoring the range of identities represented within the assortment.

A Shared Archive

Through the Queer Lens highlights images’s function in constructing neighborhood and shaping tradition. The exhibition spans personal snapshots, staged portraits, and pictures that later grew to become touchstones of queer visibility. Each {photograph} carries proof of how people navigated identification, connection, and survival by means of a altering social panorama.

By bringing these works collectively, the present creates a visible archive that resists disappearance. It reminds guests that whereas queer lives had been typically pushed to the margins, images preserved fragments of fact that would not be erased completely.

Explore the Book

Photography’s energy to seize actuality, or an in depth approximation, has all the time been intertwined with identification. Since the digital camera’s invention in 1839, queer communities have used the medium to affirm themselves, resist erasure, and have fun connection.

The Queer Lens book, printed to accompany the exhibition on the J. Paul Getty Museum (June 17–September 28, 2025), expands on these themes. It options essays by students and artists exploring queer tradition and identification, alongside a wealthy collection of photographs: portraits, visible data of kinship, and documentary images of early queer teams and protests.

![Angela Scheirl [now A. Hans Scheirl]. 1993, Photo: Catherine Opie. Silver-dye bleach print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Helen Kornblum in honor of Roxana Marcoci. © Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Naples](https://gayety.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/queer-lens-1-1-509x640.jpg)

![Angela Scheirl [now A. Hans Scheirl]. 1993, Photo: Catherine Opie. Silver-dye bleach print. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Helen Kornblum in honor of Roxana Marcoci. © Catherine Opie, Courtesy Regen Projects, Los Angeles, Lehmann Maupin, New York, Hong Kong, London, and Seoul, and Thomas Dane Gallery, London and Naples](https://gayety.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/10/queer-lens-1-1-509x640.jpg)

The quantity provides readers a deeper look into how images has formed queer visibility, making it a vital companion to the exhibition. Interested readers should buy the guide here.

Accessibility and Language

In maintaining with its mission of inclusion, the exhibition is offered in each English and Spanish. This dual-language method underscores the curators’ intent to make queer historical past accessible to wider audiences and to affirm that these tales belong to everybody.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://gayety.com/queer-lens-photography-history

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us