This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://lithub.com/what-the-picture-knows-books-that-seamlessly-blend-text-and-image/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

According to linguist David Crystal, as soon as an individual has realized to learn, it’s virtually unimaginable to course of the graphic marks that make up a letter as something however a letter. At some level, we cease trying and begin studying. If a fiction author makes use of pictures, they ask a reader each to learn and to look. It’s messy—like consuming whereas driving. Photographs additionally complicate the suspension of disbelief. If {a photograph} evidences one thing that basically occurred, what’s it doing in a narrative of imaginary occasions? These complexities may clarify why pictures in fiction are sometimes handed over in awkward silence.

John Berger makes an argument that it’s the distinction between textual content and picture that makes the mix fruitful. In an introduction to I Could Read the Sky, author Timothy O’Grady and photographer Steve Pyke’s 1997 novel about twentieth-century Irish emigration, Berger describes how “they work together, the written lines and the pictures, and they never say the same thing. They don’t know the same things, and this is the secret of living together.”

What follows is a quick, partial tour by some visible touchstones from the final century of fiction—considering, particularly, about what the image “knows” that the phrases don’t.

*

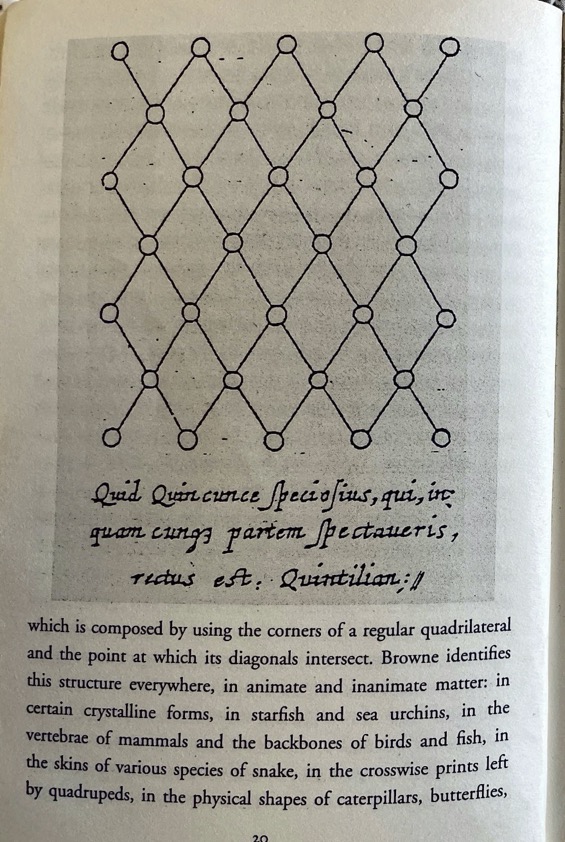

The Quincunx

WG Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn (1998) narrates a solitary stroll across the sand dunes, energy stations, and empty resorts of Suffolk. Some pictures seem like taken by the writer. The boxy Rover parked outdoors Lowestoft station is especially evocative for a British youngster of the eighties and nineties. To the identical reader, different photographs really feel extra inconceivable: the view from inside a miniature mannequin of the Temple of Jerusalem; the Dowager Empress along with her senior eunuch Li Lien-ying; a Chinese quail, captured at ground-level, “in a state of dementia.” There is the unusual feeling that the fiction itself has someway generated the pictures.

Early on, we see the “quincunx,” a lattice construction that the seventeenth-century writer and pure thinker Thomas Browne glimpsed “in the physical shapes of caterpillars, butterflies, silkworms […] the pyramids of Egypt and the mausoleum of Augustus.” It turns into clear, ultimately, that it is a visible key to the quincunx construction of the e book itself. Sebald encourages a state of studying the place epiphany and paranoia are twinned. Suddenly, each picture speaks to all of the others: a wooden scattered with lifeless our bodies, fishermen shin-deep in a glut of herring, the writer in entrance of a Lebanese cedar, accompanying a dialogue of Dutch Elm Disease.

Eyes

Sebald’s Austerlitz opens with eyes within the darkness. In the Antwerp Nocturama, the eyes of the nocturnal creatures remind the narrator of the “inquiring gaze found in certain painters and philosophers who seek to penetrate the darkness which surrounds us purely by means of looking and thinking.” Here they’re, in rectangular strips: the eyes of jerboa, owl, Jan Peter Tripp, Ludwig Wittgenstein. The narrator’s religion on this flimsy visible proof is childlike. At the identical time, it’s surprising, at the same time as an grownup, when a e book opens its eyes and appears again.

There is the unusual feeling that the fiction itself has someway generated the pictures.

In Amy Sackville’s Painter to the King (2018), the King of Spain complains to Diego Velazquez, “I’m so tired of seeing myself in your mirrors.” The novel is informed from the point-of-view of the courtroom painter. The sly, bespectacled eyes of one among his topics, Francisco de Quevedo y Villegas, look out from an early web page—it’s intimidating. The feeling of being watched lingers. For Diego, a misplaced stroke may very well be expensive.

Empty City Streets

It was by Sebald that I found the Vertigo weblog, run by Terry Pitts, which opened my eyes to the breadth of “photo-embedded literature.” Vertigo is an excellent mixture of information—Vertigo Terry at all times experiences on the variety of photographs in a e book, and the place he thinks they’ve come from—and trustworthy accounts of what it’s truly wish to learn usually tough books.

I realized that the primary mass-produced quantity to be photographically illustrated was a “tour of art, architecture, and nature” revealed in 1844 by William Henry Fox Talbot. The Pencil of Nature included pictures of Paris boulevards. They had been empty. That is as a result of pedestrians and carriages didn’t stay in entrance of the lens lengthy sufficient to be captured by Talbot’s early photographic course of, the “Talbotype.”

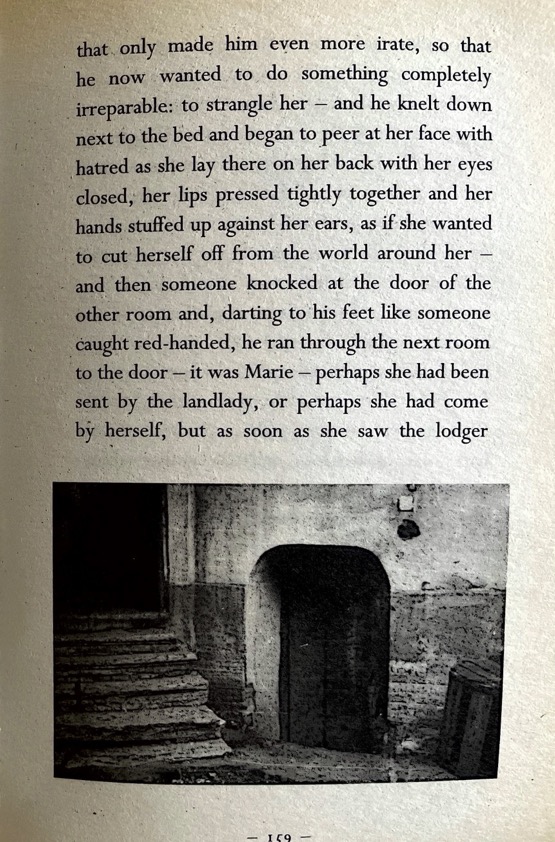

Photographs can act like an empty stage set for the motion of the phrases. Andre Breton’s Nadja (1928) is a novel in regards to the surrealist narrator’s doubtful infatuation with Nadja, a girl he meets by likelihood in the future. The textual content is excitable and wayward, whereas lots of the pictures are dramatically boring. Here are some empty brasserie tables. Here is a park fountain. This “voluntary banality,” as Michel Beaujour has referred to as it, additionally runs by Leonyd Tsypkin’s Summer in Baden-Baden (1981), about Anna and Fyodor Dostovesky’s honeymoon. Tsypkin’s account of dramatic summer time of playing and deathbed prayers is accompanied by his personal melancholic pictures of nondescript partitions and home windows, taken on a analysis journey to Leningrad. Caleb Femi’s Poor (2020) units up a visible distinction between exterior photographs of the chilly geometric grid of the North Peckham Estate, and close-up interiors with dancing. The poem “Concrete (III)” begins: “concrete is the lining of the womb / that holds boys with their mothers.”

Portraits

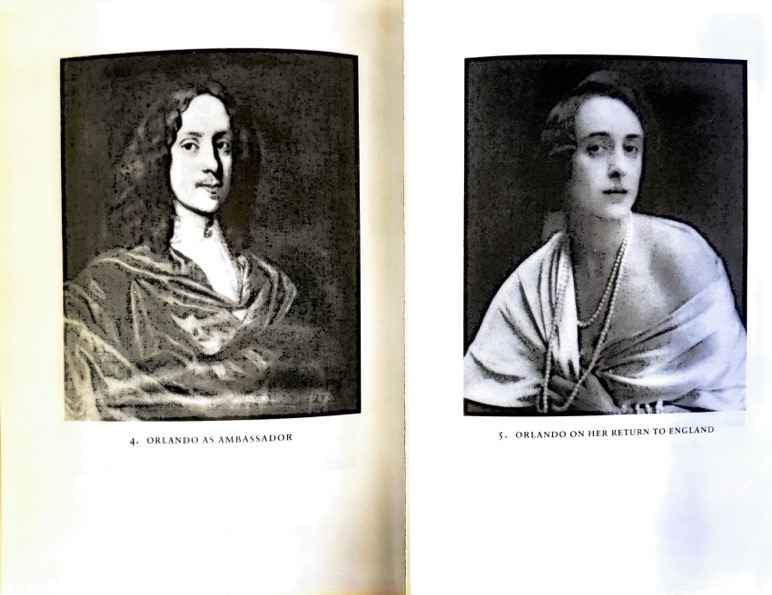

When I first learn Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928), I couldn’t get a deal with on its tone: omniscient, flippant, infatuated. It was solely once I got here to the images—printed on central plates—that I understood its parody of biography. The pictures joyfully corroborate the textual content’s account of a life that can not be the case. The first picture, “ORLANDO AS A BOY,” reveals an Elizabethan youngster. The boy ultimately grows as much as be the lady captured, roughly 350 years later, within the ultimate {photograph}, “ORLANDO AT THE PRESENT TIME.” The photographs appear to mock the concept it’s potential to entry the previous—and the arbitrary conventions of inheritance. Some of them had been staged by Woolf. The relaxation she discovered within the assortment of Knole House, the nation property the place Vita Sackville-West grew up, however couldn’t inherit as a result of she was a girl.

Handwriting

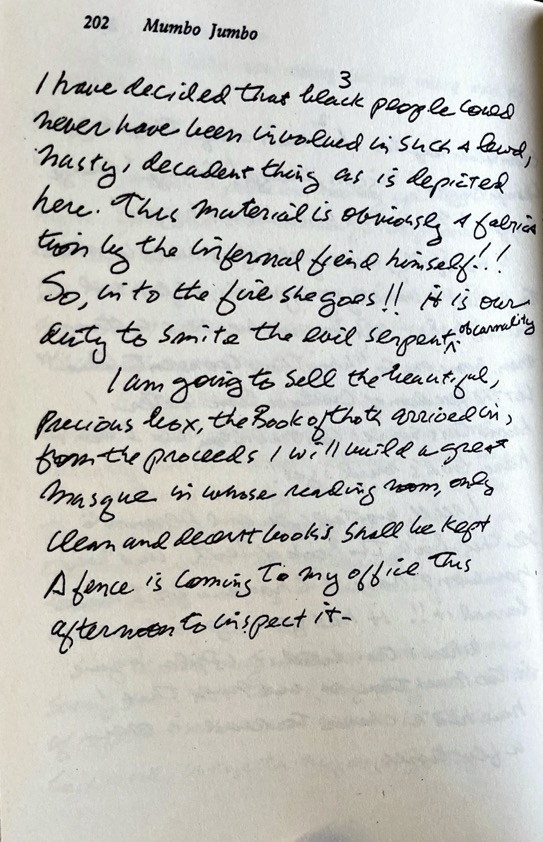

Here are simply a number of the “photo-embedded” books that comprise photographs of handwriting: Nadja, The Rings of Saturn, Theresa Hak Kyung Cha’s Dictee (1982), Javier Marias’s Dark Back of Time (2001), Mumbo Jumbo by Ishmael Reed (1972). All of those writers wish to present us that somebody, sooner or later, actually used a pen. Perhaps using pictures induces a nostalgia for an imagined time earlier than images existed? Perhaps it makes writers anxious that writing itself, as a bodily exercise, will probably be changed? Perhaps writers ought to get out extra usually?

What Cannot Be Seen

In Valeria Luiselli’s Lost Children Archive (2019), two adults and two youngsters go on a highway journey by the American South. The sun-bleached polaroids taken by the narrator’s son are a part of the novel’s exploration of “documentation.” For unaccompanied migrant youngsters passing by the identical panorama, lack of acceptable proof may be a matter of life and loss of life. In Esther Kinsky’s River (2018), the narrator—whose father was an newbie photographer—picks up an previous polaroid digital camera and takes it along with her on her walks alongside the river Lea in East London. The photographs appear to seize one thing greater than the sunshine reflecting off the floor in entrance of the lens: “The images belonged to a past I could not even be sure was my own, touching on something whose name I must have forgotten, or possible never knew.”

__________________________________

Mr. Outside by Caleb Klaces is accessible from Prototype Publishing.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you’ll be able to go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://lithub.com/what-the-picture-knows-books-that-seamlessly-blend-text-and-image/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us