This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/2026/02/chief-buffalo-child-long-lance-native-american-identity/685326/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

In 1928, Chief Buffalo Child Long Lance printed a memoir that triggered a sensation within the literary world. It opened together with his earliest reminiscence: Barely a 12 months outdated, he was driving in a moss child provider on his mom’s again, surrounded by ladies and horses. His mom’s hand was bleeding, and he or she was crying. Long Lance wrote that when he’d recounted this reminiscence to his aunt years later, he’d been instructed that he was remembering the “exciting aftermath of an Indian fight” through which his uncle Iron Blanket had simply been killed by the Blackfeet Tribe’s conventional enemies, the Crow. His mom’s hand was bleeding as a result of she had amputated her personal finger in mourning.

His subsequent reminiscence was of falling off a horse at age 4. “From this incident on,” he wrote, “I remember things distinctly. I remember moving about over the prairies from camp to camp.” Born to a Blackfeet warrior within the late nineteenth century, through the last days of the “free” Blackfeet in northern Montana and southern Alberta, Long Lance wrote that his father’s technology was going through “the mystery of the future in relation to the coming of the White Man.”

Long Lance attended the notorious Carlisle Indian Industrial School in Pennsylvania, and obtained a presidential appointment to West Point. Eager to combat within the Great War even earlier than America entered the battle, he traveled to Montreal in 1916 to enlist within the Canadian Expeditionary Force, fought at Vimy Ridge, and was twice wounded. The second wound knocked him out of fight, however not—he would later boast—earlier than he’d risen to the rank of captain and was awarded the Croix de Guerre.

By the time his memoir got here out, Long Lance had traveled an ideal distance—from the High Plains to New York excessive society. One evening within the winter of 1928, he noticed Natacha Rambova, the ex-wife of the silent-film star Rudolph Valentino, within the Crystal Room of the Ritz-Carlton. According to his biographer, Donald B. Smith, Long Lance approached Rambova and requested her to bounce. They started an affair, however she wasn’t the one girl in his life: Long Lance was additionally linked to the actor Mildred McCoy, the singer Vivian Hart, and Princess Alexandra Victoria of the House of Glücksburg.

Long Lance was shockingly good-looking, broad-shouldered and wasp-waisted, with easy, coppery pores and skin and thick black hair. He did calisthenics and gymnastics each morning and wrestling when he may discover companions. He had boxed with the world heavyweight champion Jack Dempsey and been a coaching associate for the legendary Olympian Jim Thorpe, a member of the Sac and Fox and Potawatomi Nations.

When Long Lance’s memoir was printed, the deliberate preliminary run of three,000 copies was bumped to 10,000 on the energy of early reads and the endorsement of The Saturday Evening Post ’s Irvin S. Cobb, then one of the most influential journalists in the world. (Cobb additionally wrote the ebook’s foreword.) Reviews of the memoir had been fulsome. The New Orleans Times-Picayune declared it “the most important Americana offered this year.” The Philadelphia Public Ledger averred that Long Lance had written “a gorgeous saga of the Indian Race.” In the New York Herald Tribune, an anthropologist known as the ebook an “unusually faithful account” of a Native American’s childhood and early manhood. Across the Atlantic, The New Statesman declared that the memoir “rings true; no outsider could explain so clearly how the Indians felt.”

By 1930, Long Lance’s superstar prolonged far past New York ballrooms and newspaper ebook evaluations: He starred in a function movie, The Silent Enemy, a few famine that strikes a fictionalized model of the Ojibwe Tribe. The B. F. Goodrich Company deliberate to supply an experimental canvas operating shoe modeled after a Plains Indian moccasin like these Long Lance had worn.

But simply two years later, he can be found dead on a wealthy white girl’s property in California, killed by a self-inflicted gunshot wound to the pinnacle. By this level he was almost penniless, exiled from excessive society, and besieged by accusations that he wasn’t who he stated he was—that he’d leveraged a bogus id to rise on the earth.

Before I left the Leech Lake Ojibwe reservation in northern Minnesota, I didn’t actually assume or discuss a lot about being Native. My “Indianness” wasn’t vital to me. When I used to be rising up, my Ojibwe mom—and in addition my Austrian Jewish father—made positive that I harvested wild rice within the fall, hunted within the winter, tapped maple bushes for sugar within the spring, and fished and picked berries in the summertime. I hated all that stuff, which I skilled as alternatives for my dad and mom to remark incessantly on my laziness, my poor work ethic, my dearth of talent when jigging rice or boiling down maple sap or sitting stand for deer.

Only after I moved away did questions on being Indian start to preoccupy me. When I began at Princeton in 1988, I used to be stunned by how few folks had heard of my tribe, not to mention my reservation. And as a light-skinned nerd who cherished Dungeons & Dragons, grew up middle-class, and didn’t “look” Indian, I did not scan as Native to most individuals. I started to really feel {that a} battle was being waged between how I used to be seen from the surface and what I felt myself to be on the within—whilst I wasn’t but positive who I felt myself to be on the within. It turned clear to me that, so long as you look iconographically Native—copper pores and skin, black hair, a thousand-yard stare aimed on the previous—white folks will invariably consider any rattling factor you need to say.

So I attempted to construct a Native id from the surface in. I received the belt buckle, wore the bolo tie, grew my hair lengthy, listened to R. Carlos Nakai’s flute recordings and John Trudell’s spoken-word CDs. I started to domesticate “life on the rez” tales that I shared with anybody who would pay attention. I discovered myself changing into outspoken—and harsh—about what was Indian and what was not; who was “legit” and who was “fake”; what was “Ojibwe” and what was “not Ojibwe.” I notice now that each one of this frenzy round id was much less a politics than a pathology.

But for Native Americans, race is just not merely a social assemble. It is a authorized class from which rights and financial advantages move. Whether or not you’re enrolled in a federally acknowledged tribe determines the place and how one can hunt, whether or not you qualify for sure scholarships, the place you may dwell (and whether or not you get housing subsidies), whether or not you get a share of tribal income, and in some instances which educational or authorities jobs you’re given particular consideration for. But to be an enrolled member of a tribe is sort of fully contingent on “blood quantum”—the proportion of 1’s lineage that may be traced to tribal ancestors.

I don’t qualify for enrollment in my tribe. To be enrolled within the Minnesota Chippewa Tribe, you want a quantum of one-quarter Minnesota Chippewa Tribe blood, in addition to one dad or mum who’s an enrolled member. (Chippewa is a French corruption of the unique Ojibwe.) Even although my mom grew up on Leech Lake and devoted her life to the tribe, first as a nurse after which as a lawyer and tribal-court choose, her official blood quantum is simply one-quarter. Her grandmother was recorded as half Ojibwe, although she was full, and her father was on the rolls as 1 / 4 when he was actually half. I ought to be enrolled. The indisputable fact that I ought to be however am not turned the concept of Native blood into an obsession for me, at the very least for some time, as a result of it was a measure of my Indianness that I couldn’t change.

Within my lifetime, the query of what constitutes Native id and qualifies one for enrollment has solely grown extra fraught. For a lot of U.S. historical past, being Indian was not a useful factor; the other, the truth is, was true. But within the Seventies, new federal legal guidelines modified the expertise of Indianness for a lot of Native folks. So a lot in order that by the point I used to be a teen, having Indian id was not essentially one thing that might maintain you again, however a fabric profit. It would possibly assist you discover a job, win an arts grant, or entitle you to substantial earnings from on line casino income.

Inevitably, this led to outsiders—verifiably non-Indian of us—making an attempt to say Indian id. Jobs, particularly in academia, have gone to folks feigning Native id, akin to Andrea Smith (who claims to be Cherokee regardless of no credible proof that she is) at UC Riverside and Elizabeth Hoover (who claimed to be Mohawk and Mi’kmaq, and later apologized when she found she was not) at UC Berkeley. The identical is true in publishing: Margaret Seltzer sold her memoir, Love and Consequences, on the premise of its particulars about her grisly childhood as a Native child in foster care in Los Angeles—however Seltzer was not Native and grew up with a loving household in Sherman Oaks. Nativeness offered as trauma porn (however with the potential for a hopeful consequence!) could be profitable.

For Natives, it’s enraging that, now that being Indian lastly has important, remunerative alternatives hooked up to it, imposters have swooped in to take what’s—by blood, historical past, and struggling—rightfully ours. By about 2010, these imposters had come to be referred to as Pretendians, they usually sparked a countermovement of Pretendian-hunting. A coterie of self-styled guardians of Indian id arose, largely on social media, to name out interlopers. I understood the impulse. I’d accomplished my share of such policing as a younger man earlier than I noticed that it was the product of insecurity about my very own Indian id, and grew out of it.

The Pretendian hunters weren’t all the time curious about a full accounting of the info earlier than announcing an individual legitimately Native or a fraud. Many fairly genuine Natives had been focused for banishment, and the ugly infighting their work impressed was lined broadly—by the requirements of Indian affairs—within the American media, which noticed the battles as a part of the bigger id wars raging throughout the nation within the new millennium.

For now, the Pretendian hunts have quieted slightly, the hunters having misplaced credibility due to their overzealousness, and the nation having grown weary of id politics. But it’s not simply the Pretendian hunters who’ve culled the rolls. Some small tribes, discovering themselves immediately wealthy from on line casino income, have been disenrolling members, in order to make sure extra money for individuals who stay. Other tribes—sometimes giant ones with substantial diasporas—have additionally been cleansing their enrollment data, much less to hoard cash than to mitigate tribal anxieties about acculturation. One approach to really feel extra “Indian” is by performing a racial alchemy that successfully turns liminal of us into white folks. All of this has given new urgency to outdated and confounding questions: Who will get to be Indian, and who decides?

For a very long time, the federal authorities wasn’t a lot curious about defining who was and wasn’t Indian. From the nation’s start, Native folks had been largely exterior its embrace. In 1787, the Founders explicitly excluded Native folks from the U.S. Constitution. “Congress shall have Power,” Article I declares, to “regulate Commerce with foreign Nations, and among the several States, and with the Indian Tribes.” We had been understood to belong to our personal sovereign tribal nations (then numbering properly over 750), a lot of which had been geographically inside but civically separate from the rising American republic. We had our personal legal guidelines, methods of presidency, and standards for citizenship.

The authorities started bearing down more durable on who was or wasn’t Native after the passage of the Indian Removal Act of 1830, which resulted within the Trail of Tears and the pressured displacement of about 100,000 Indians from east of the Mississippi to the Indian territories from 1830 to 1850. By 1887, the U.S. authorities cared an ideal deal about who belonged to these tribal nations. That 12 months, Congress handed the Dawes Act, in any other case referred to as the General Allotment Act. It was, even for that point, a remarkably cynical piece of laws. To clear up what the federal government endured in calling “the Indian problem,” the president was given permission to interrupt up communally held tribal land into smaller parcels that might be “allotted” to particular person Indians and heads of households. The acknowledged motive for the legislation was that personal possession and farming would induce Indians to surrender the tribal cultures and practices that—within the legislators’ considering—had been holding again Native folks and the nation as an entire, holding each Indian and white Americans from their full financial potential. In different phrases, the official rationale for the Dawes Act was financial salvation by way of assimilation.

But the true intent of the laws was to permit the state to steal Indian land and escape treaty obligations. At the time, Native nations held roughly 150 million acres in combination, however the variety of people who would obtain allotments (typically set at 160 acres every) was so small that hundreds of thousands of acres of “surplus” land can be left open to white settlement. And as soon as the entire Indians turned farmers and stopped being Indian, the lawmakers’ considering went, the tribes would disintegrate. The authorities would finally be freed from its treaty obligations to sovereign Indian nations—as a result of there can be no nations left.

To determine who received an allotment, the federal government needed to decide who was really Indian. So the federal government started enrolling Indians in tribes, utilizing blood (gleaned by way of census knowledge) as a metric.

In 1924, Congress handed the Indian Citizenship Act, also called the Snyder Act, which turned all noncitizen Indians born throughout the territorial limits of the United States into “citizens of the United States,” however with out affecting “the right of any Indian to tribal or other property.”

That last clause of the act was essential and hard-won. It meant that even after having the mantle of American citizenship thrown over us, whether or not we wished it or not, we didn’t have to completely hand over being legally Indian. We successfully had twin citizenship: Indians had been, lastly, American en masse, and but we remained members of our sovereign Indian nations.

The laws was controversial amongst some Native nations. The Onondaga, members of the Iroquois Confederacy, wrote a letter to President Calvin Coolidge declaring that the Snyder Act was treasonous as a result of it compelled their residents to turn into American with out their consent. For almost 150 years, Indians had been barred from being a part of the American franchise; now we had been pressured to be American.

In the early Seventies, President Richard Nixon introduced a brand new shift towards tribal self-determination. In concept, this coverage meant that tribes may resolve for themselves whom to enroll. In apply, this has solely sophisticated issues: Although tribes now have extra autonomy to are likely to their very own collective futures, they have to accomplish that in ways in which don’t threaten federal recognition. Navigating between autonomy and nonexistence is just not simple. In 1994, when the Blackfeet Nation in Montana toyed with ending blood quantum as a metric for enrollment, an official from the Bureau of Indian Affairs warned that if the tribe “diluted” its membership, it’d uncover that it had “ ‘self-determined’ its sovereignty away.”

In November 1928, Long Lance arrived in Ontario to start capturing The Silent Enemy, a part-talkie movie that follows a band of Indians in Canada as they battle in opposition to hunger. During filming, in line with Donald Smith’s biography, Long Lance entertained the Ojibwe actors and crew with warfare dances and conventional storytelling, typically accompanied by an assistant director—Ilya Tolstoy, the Russian novelist’s grandson.

One of his co-stars was Chauncey Yellow Robe. Yellow Robe had been born into the Sičháŋǧu Oyáte in 1867, and had been 9 years outdated on the time of the Battle of the Little Bighorn. His maternal great-uncle was none aside from Sitting Bull. In 1883, at age 15 or 16, he, too, had been taken to the Carlisle Indian boarding school. That’s the place he was when roughly 300 of his kin, largely ladies and youngsters, had been gunned down at Wounded Knee Creek in 1890. Now, as Yellow Robe watched Long Lance, he was disturbed: Something concerning the Blackfeet chief appeared off. Long Lance’s dancing didn’t take a look at all to him just like the dancing of Plains tribes.

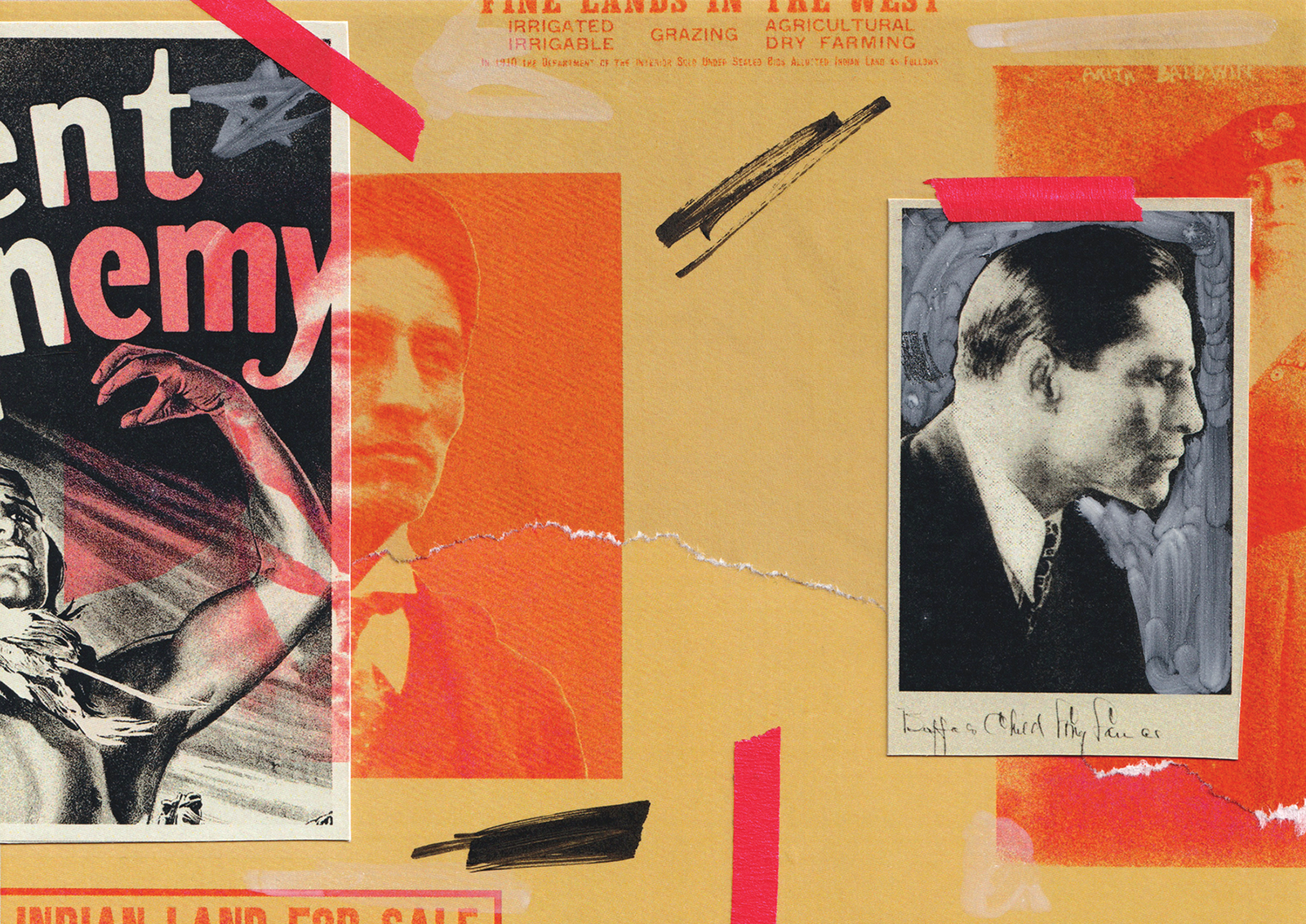

Illustration by Paul Spella1

Far left: A film poster for The Silent Enemy. Center left: Long Lance’s co-star Chauncey Yellow Robe, whose great-uncle was Sitting Bull. Center proper: The creator photograph accompanying an article Long Lance wrote for Maclean’s in 1929. Far proper: Anita Baldwin, the eccentric heiress who employed him earlier than his demise.

When Yellow Robe returned to New York, he contacted the Bureau of Indian Affairs and instructed them of his suspicions. It turned out that the workplace was already investigating questions on Long Lance’s origins.

When Long Lance’s memoir was printed, the Cosmopolitan Book Corporation despatched a duplicate to Charles Burke, the U.S. commissioner of Indian affairs. “The emotional reaction of those who have read it is enthusiastically favorable,” the quilt letter learn. “It would interest us very much to know what you think of ‘Long Lance.’ ”

Intrigued by the ebook however skeptical about its creator, Burke began writing letters. First, he contacted the U.S. Department of War, asking about Long Lance’s profession at West Point. Two days later, he heard again that Long Lance had failed the West Point entrance exams, and by no means attended. Burke wrote extra letters. From an Indigenous commissioner in Canada, Burke discovered that Long Lance was a Blackfeet chief solely in an “honorary capacity.”

Was he Blackfeet in any respect? Burke obtained a letter from Percy Little Dog, the interpreter for one of many tribes that make up the Blackfoot Confederacy. “We never saw or heard a thing about ‘Buffalo Child Long Lance’ until the winter of 1922,” Little Dog wrote. “He is not a Blood Indian, and has no tribal rights on the Reserve. We have heard he was a Cherokee Indian, but do not know definitely who he is or where he came from.” The former superintendent of the Carlisle Indian boarding college wrote as properly, offering Long Lance’s actual title, Sylvester Long, and saying that he had attended the college—however as a Cherokee, not a Blackfeet.

In November 1929, Long Lance gave a chat on the American Museum of Natural History titled “An Indian’s Story of His People.” Two months later, on January 28, 1930, he attended a banquet for the Poetry Society of America on the Biltmore Hotel. After dinner, he regaled America’s literary elite with a efficiency of Plains Indian signal language, and in entrance of a whole bunch, he recited his personal Blackfeet demise track, which went, partly: “The Outward Trail is no longer dark, / I see—I understand: / There is no life, there is no death; / I shall walk on a trail of stars.”

Every week after that, he was on the Mutual Life Building on the nook of Broadway and Liberty, the place he had been summoned to fulfill with William Chanler, a producer and the authorized counsel for The Silent Enemy. When Long Lance opened the door to the workplace, Chanler greeted him by saying “Hello, Sylvester.” Long Lance checked out Chanler steadily. “Sylvester? Who’s Sylvester?” Chanler was enraged: “You’re Sylvester—Sylvester Long. You come from North Carolina, and you’re not a blood Indian.”

The charade was uncovered. Long Lance was not Blackfeet. He was not even a full-blooded Indian. He had not grown up on the Plains. He had not hunted bison together with his folks. He had not been a captain within the Canadian military. He had not received the Croix de Guerre.

As Donald Smith recounts in Long Lance: The True Story of an Imposter, Sylvester Long was born on December 1, 1890, in Winston (at the moment Winston-Salem), North Carolina. In town registry, his household was listed as Black. His father, Joe Long, a janitor on the West End School, had been born into slavery in 1853. His mom, Sallie Long, had been born into slavery as properly. His brother Abe Long was the supervisor of the all-Black balcony on the native theater. Beginning at age 6, Sylvester had walked two miles every approach to the Depot Street School for Negroes. And though it was true that he had attended the Carlisle Indian boarding college, his software stated that he was half Cherokee, not Blackfeet.

After that February day in 1930, Long Lance’s life fell aside, at first steadily after which immediately. He was invited to fewer and fewer society features and obtained so much much less consideration from princesses and starlets; there can be no extra lectures, no extra films, and no extra books. Public response to his fraudulence was ferocious. When Irvin Cobb, the Saturday Evening Post author who’d touted his ebook, received the information, he was incensed. “To think that we had him here in the house,” he stated, ever the son of Paducah, Kentucky. “We’re so ashamed! We entertained a nigger.”

As he retreated from public life, Long Lance eked out a quiet existence in New York till the early spring of 1931, when Anita Baldwin, an eccentric millionaire heiress, supplied him a job as her secretary and bodyguard on an prolonged journey to Europe within the fall. Baldwin would later say publicly that whereas in Europe, Long Lance confirmed himself to be “a man of estimable character and gentlemanly in all respects.”

But in her non-public journals and correspondence, she recorded that he drank closely and made a number of suicide makes an attempt. When the journey ended, Baldwin left him in New York and continued on to California, the place she lived. He wrote pleading letters asking to be rehired. She promised that if he stopped consuming and chasing ladies, she would pay for flying classes and provides him a airplane. He traveled to California, the place he rented a lodge room in Glendale and visited Baldwin’s property typically, however he sensed that she was cautious of him. He wasn’t improper: According to Smith, she was having Long Lance adopted by a personal detective, as a result of he was consuming and womanizing once more, and spending time with an unsavory crowd.

On March 19, 1932, after going to a film, Long Lance instructed a taxi driver to take him to Baldwin’s property. He sat with Baldwin within the library. According to her, he appeared “abrupt, very depressed and non-communicative.” Not lengthy after she retired to mattress, she heard a gunshot. Baldwin’s watchman ran to the library, the place in line with Smith’s biography he discovered Long Lance “slumped on a leather settee,” his legs straight out in entrance of him, his head flung again, and a Colt .45 revolver in his proper hand.

In May 2024, I traveled to East Glacier, Montana, on the western fringe of the Blackfeet Nation, for lunch on the Two Medicine Grill. I used to be there to fulfill a Blackfeet named Robert Hall. When he arrived, it took him a couple of minutes to get from the door to the place I used to be sitting as a result of so many individuals within the restaurant appeared to be a good friend or a relative—the server, the prepare dinner, a few diners.

I wished to speak with Hall concerning the scourge of Pretendians. In 2020, Hall had waded into an internet trolling battle with anti-Pretendians, involved that of their zealotry for rooting out pretend Indians, these crusaders had turn into “toxic.” Pretendian-hunting, in his view, “had become this thing where if you don’t agree with the hunters, you’re not Indian anymore.” All of which, in Hall’s view, simply deepens Indian wounds concerning id and tribal belonging.

When Hall received to my desk and we began speaking, I famous that he spoke in that clipped, laconic approach I’d come to acknowledge as very Blackfeet. He has spent nearly his entire life on the reservation. “I’ll die here, I hope,” he stated. “My whole paradigm is ‘Blackfeet rez.’ ”

But he dislikes the anti-Pretendian crusading as a result of it deepens the give attention to blood quantum. And he has quite a lot of objections to the blood quantum: It’s a colonial system whose function was to vanish us, it’s divisive and harmful for the Indian neighborhood, and its use erodes tribal sovereignty. Reliance on blood quantum forces us to combat each other, and rely our fractions, once we ought to be combating collectively for a more healthy future. The subject can also be deeply private for Hall—his tribal council has granted and rescinded his personal enrollment, all primarily based on evolving interpretations of outdated paperwork about an ancestor. That ancestor, his great-great-grandmother Mary Ground, was initially put down within the rolls as full-blooded Blackfeet. But, in line with Hall, the rolls burned in a hearth, and when the tribe composed them once more, Mary Ground was put down as quarter-blooded. So Hall was deemed unqualified. Not lengthy after that, although, his household discovered further paperwork, and he was lastly enrolled.

And then, in January 2024—because it occurred, the day after Lily Gladstone, the actor of blended Blackfeet descent who won a Golden Globe for her role in Killers of the Flower Moon, publicly thanked Hall for the Blackfoot-language instruction he’d given her—the council rescinded his enrollment. After that, Hall obtained nonetheless extra info and documentation, together with an affidavit from his paternal grandfather, whose blood had by no means been accounted for. “We take that back to the council,” he recalled, “and it passed. And we’re back on.”

“I spent 37 years not enrolled,” Hall instructed me. “Man, being enrolled was like finally regaining a limb you’d never had. And then the council comes along and chops it off. And they say, ‘Oh, it’s nothing personal.’ But it’s all personal.”

The vagaries of blood quantum imply that it’s doable to be a “card carrying” Indian with out ever having lived on a reservation or understanding every other Indians. It’s doable to be an enrolled Indian and have completely no information of your tradition. It’s doable to be one hundred pc Native by blood and never be enrolled. And it’s doable to develop up Indian—steeped in your tribal methods, a speaker of your language, a keeper of cultural information—and but nonetheless be, within the eyes of the federal government, white.

Hall understands that Pretendianism isn’t some imaginary downside; it’s an actual subject. “It’s like, to be in our special-hat club, you need this special hat. And then someone from fucking Pennsylvania finds a hat in their basement and puts it on and is like, ‘Oh, hey, look at me—I’m you!’ and you’re like, ‘Ummmm, are you?’ ” This is the lure we discover ourselves in: “Blood matters, even as a spiritual connection to our ancestors.”

As we talked, I felt an outdated unhappiness properly up in me. By 1900, solely a treasured few Blackfeet had made it by way of the gantlet of smallpox, warfare, hunger, and Christianization. Closer to residence, my mom’s household survived the consequences of Indian boarding faculties, abuse, neglect, violence, and crushing poverty. We Natives, collectively, have survived an incredible quantity. Across the nation, many people received the survival lottery, in some instances with our traditions and our kin in place, and right here we’re within the 2020s, losing these winnings measuring each other’s blood quantum and combating with each other in pointless internecine cultural battles.

After school, I moved again residence to Leech Lake. I noticed that I had missed harvesting wild rice, and fishing, and tapping maple bushes. I discovered find out how to lure beaver and pine marten. I had missed my household, my tribe, the land, all of which meant extra to me than the skinny regard of white folks. My older brother, Anton, who had been a historical past professor in Wisconsin, moved residence as properly. He fell in love with, and was rapidly devoted to, our Ojibwe cultural practices, attending Big Drum ceremonies and medication dances. Both of us began finding out the Ojibwe language. Both of us realized, for various causes and in several methods, that we preferred our folks, and that we preferred being Indian as a lot as or greater than we preferred being the rest. And I found that the extra immersed I felt in Indianness, as a lifestyle lived in neighborhood quite than an imagined assemble, the much less I apprehensive about what different folks considered how I regarded, or whether or not I used to be enrolled.

For some—like Robert Hall and my brother and me—the query of whether or not we’re correctly Indian or not, tribally enrolled or not, is principally a matter of id and belonging, of being allowed to be who we actually are by dint of our histories and our attachment to the neighborhood and our affinity for tribal folkways and tradition, in addition to our blood. Enrollment standing doesn’t instantly have an effect on our capability to feed our households, or get medical care, or have a roof over our head in our personal neighborhood. For others, nevertheless, being disenrolled has penalties extra tangible than the lack of belonging.

Consider Sally Brownfield, who lived for years as a member of the Squaxin Island Tribe west of Tacoma, Washington, working as a trainer who specialised in Indigenous schooling. Her mom, Sally Selvidge, spent many years working to make sure entry to good well being look after the tribe; the tribe’s well being clinic is known as for Selvidge, who died in 1994. But Brownfield herself, who served on the tribe’s enrollment committee till final 12 months, can not get backed care at her mom’s clinic, as The Seattle Times reported last spring, as a result of she and dozens of different tribe members had been just lately disenrolled. In her case, the tribe says that, though she possesses Indigenous blood by way of her mom, they don’t descend from a choose listing of Squaxin ancestors, and so by no means ought to have been enrolled within the first place. Nor can Brownfield vote in Squaxin elections, or harvest clams on the Salish Sea seashores the place her ancestors did so for generations. Others who had been disenrolled alongside her misplaced their backed tribal housing.

Something related unfolded not distant a few decade in the past, in Washington’s Cascade Mountains, close to the Canadian border, the place the Nooksack Tribe disenrolled 306 members. Tribal officers say “the 306” (as they got here to be known as) had been largely descended from a special tribe, and didn’t meet the one-quarter blood quantum required for enrollment. All 306 misplaced their official Nooksack enrollment for need of ample documentation, although many had lived in the neighborhood for many years, if not their entire life. At least 20 had been evicted from their household properties on tribal property.

The irony is that we Natives—who can lay genuine declare to being the primary Americans, and who had been then deemed formally not American by the Constitution earlier than being pressured to be American by American legislation—at the moment are on the mercy of our personal tribal nations relating to whether or not we could be thought-about actually Indian, with all of the psychological and sensible advantages that id confers. We’ve suffered sufficient over the centuries, by the hands of European powers after which the federal authorities of the United States. To now endure censure by overzealous anti-Pretendian crusaders, and banishment by bureaucratic tribal decrees and reactionary blood-quantum guidelines, feels significantly bitter.

I first wrote about Long Lance nearly 20 years ago. I ended that story by revealing his fraudulent Blackfeet id. In my account, he was Black, not Native. Case closed.

But the case turned out to not be closed. He was Indian in spite of everything. The proof was there, however I’d blinded myself to it as a result of I nonetheless noticed id in black and white—or Black and Red.

As Smith detailed in Long Lance: The True Story of an Imposter, Long Lance’s mom, Sallie, had been born into slavery. Her grandfather Robert Carson was “a small-time slave owner.” Carson had been wild in his youth, however evidently “settled down after he bought a handsome Indian woman” at an public sale.

Among the 20 kids that Indian girl gave start to was Long Lance’s grandmother Adeline, born in 1848. Long Lance’s maternal grandfather was a North Carolina state senator who visited Carson’s plantation typically and fathered Sallie and one other youngster with Adeline.

It seems that Long Lance’s father, too, had Indian blood. He was born into slavery in 1853 and early on in life was separated from his mom. When Joe Long lastly discovered his mom in Alabama, some 40 years later, she instructed him that his father was white—and that she herself was Cherokee. When Joe died, his obituary acknowledged that he was “a member of the Catawba tribe of Indians.” In 1887, Joe and Sallie Long moved to Winston, North Carolina, the place the racial codes had been way more inflexible: The solely two classes for human beings had been “white” and “colored.” The Longs fell squarely into the “colored” class. Were they Native? Yes. Were they Black? Also sure. Were they white? Yes once more.

Long Lance elided the Black in favor of the Native. When he entered Carlisle, he was listed as half Cherokee and half Croatan. Over time, he slid away from his “mixed” id; when he obtained a West Point appointment from President Woodrow Wilson, he claimed to be full-blooded Cherokee. After settling in Canada following World War I—he genuinely was wounded in battle—he started sliding away from his Cherokee-ness, too, ultimately giving it up in favor of being Blackfeet.

I believe I can perceive the slide, and the lies it entailed. One id, maybe essentially the most “authentic” one, is a narrative of enslavement and rape and subjugation, the small print of which might relegate Long Lance to life as a second-class citizen. Another, nearly fully fictive id would afford him freedom and adulation.

It’s no marvel that Long Lance wished to be a type of Indian that didn’t exist—besides in dime-store novels and, later, films—and possibly by no means had; that he mined the mineral of racial nostalgia for a previous that by no means was. He mined it till it was performed out for him, and he died alone, unemployed, bereft, and heartbroken. Not as Cherokee or Blackfeet or Black and even white—however as maybe one of the crucial American identities of all: self-made.

*Lead picture: Illustration by Paul Spella. Sources: Atlanta Journal-Constitution / AP; Hulton Archive / Getty; Frances Benjamin Johnston / Library of Congress / Corbis / VCG / Getty.

1Second picture: Illustration by Paul Spella. Sources: LMPC / Getty; Wikimedia; Maclean’s; Sepia Times / Universal Images Group / Getty.

This article seems within the February 2026 print version with the headline “Who Gets to Be Indian—And Who Decides?”

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/2026/02/chief-buffalo-child-long-lance-native-american-identity/685326/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us