This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/2026/01/slavery-museums-black-history-lynching/685660/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

Belzoni, Mississippi, a city of about 2,000 individuals, is called the “Catfish Capital of the World”; it’s also often called the location of one of many first civil-rights-era lynchings. On May 7, 1955, two members of the native White Citizens’ Council shot into the cab of Reverend George Lee’s automobile; the bullets ripped off the decrease half of his face. Lee had been a co-founder of the city’s NAACP chapter and the primary Black particular person to efficiently register to vote in Humphreys County since Reconstruction. He’d additionally registered about 100 of his fellow Black residents to vote, a exceptional feat given Belzoni’s dimension and the ever-present menace of violence in opposition to Black individuals all through the South who dared to train their franchise throughout the Jim Crow period.

The Mississippi NAACP, led by Medgar Evers, started to analyze the dying as a homicide. But the county sheriff rejected the concept there had been any foul play, as an alternative suggesting that Lee had died in a automobile accident and that the lead bullets detected in his jaw had been merely dental fillings. The native prosecutor refused to maneuver ahead with the case, and the white males went free.

I realized this story just lately, after visiting the National Memorial for Peace and Justice—identified to many because the National Lynching Memorial—in Montgomery, Alabama. The memorial consists of greater than 800 rectangular metal pillars, every representing a distinct county by which a lynching occurred. One of them is Humphreys, in Mississippi.

It was a chilly, wet day, and my first time seeing the memorial. The house is haunting in its stillness, and overwhelming in its scale. Some of the metal pillars are suspended from above, whereas others are nearer to the bottom, forcing you to stroll amongst them, via a metal labyrinth of racial terror.

A person named Lee Perkins was additionally on the memorial that day, being pushed round in a wheelchair by his son-in-law Chris Brown. Perkins was born in Belzoni in 1937. He was 17 when the lynching occurred. As he advised me about rising up as a Black youngster within the Mississippi Delta, he seemed up, his eyes tracing the pillars’ lengthy, nonetheless our bodies. He had a rough voice with a heat southern drawl. “I never thought I would see something like this,” he stated, his neck craning to learn the names on each bit of metal. Dusk started to settle round us, and the sky slowly darkened at its edges.

“I pray to God they never get rid of this history,” Brown stated. “We as a Black race went through so much, and they’re trying to erase that.”

The lynching memorial has two sister websites in Montgomery—the Legacy Museum, which traces the historical past of Black oppression in America from slavery to Jim Crow to mass incarceration, and Freedom Monument Sculpture Park, a 17-acre website that makes use of each modern sculptures and authentic artifacts to light up the lives and experiences of enslaved individuals. All three had been created by the Equal Justice Initiative, a nonprofit authorized group based in 1989 that has expanded into narrative and public-history work over the previous decade and a half underneath the management of its founder and govt director, Bryan Stevenson.

Stevenson started his profession as a public-interest lawyer, and went on to argue in entrance of the Supreme Court on 5 events, profitable favorable judgments in all however one. He efficiently argued, for instance, in opposition to necessary life sentences with out parole for youngsters, and for incarcerated individuals with dementia to be protected, in some circumstances, from execution. But he has stated that as time handed, he got here to know that his authorized work wouldn’t be sufficient by itself to impact significant criminal-justice reform. The American public, he felt, wanted a deeper understanding of how the realities of the nation’s historical past formed the present-day system.

The Legacy Museum, which opened virtually eight years in the past, is maybe the closest factor America has to a nationwide slavery museum. Crucially, nonetheless, it’s fully privately funded, receiving no state or federal monetary assist. As such, Stevenson and his colleagues are unburdened by govt orders; they needn’t bow to stress to change an exhibit after a presidential Truth Social put up. I wished to get a way of how guests had been experiencing the museum and memorials now, when a lot of what they depict represents the very historical past that the Trump administration goals to de-emphasize—if not outright erase—at faculties, historic websites, and museums throughout the nation. I additionally puzzled how Stevenson thought in regards to the position these areas play at this time, in contrast with once they first opened, and what sorts of information he hoped they could be capable of present to the visiting public because the nation and its politics change round them.

Erasure was a recurring theme among the many individuals I spoke with in Montgomery. On the alternative aspect of the memorial, I met two Black girls, Jackie Brown and Annette Pinckney, who had been additionally visiting for the primary time. “We’re from Florida, where you have Governor Ron DeSantis, who is trying to erase our history,” Pinckney stated.

Pinckney is an assistant principal at a highschool in South Florida, and he or she has seen firsthand the impression of the state’s latest legal guidelines—such because the Stop WOKE Act—that regulate how faculties and companies cope with problems with race and gender. The Florida Department of Education has additionally banned AP African American Studies from being provided in Florida excessive faculties, claiming that the curriculum lacks “educational value and historical accuracy.”

Earlier of their go to, Pinckney and Brown had stood inside an actual former slave cabin situated alongside the Alabama River, on which 1000’s of enslaved individuals had as soon as been trafficked. They described feeling the biting wind whistle into the cabin via holes within the wood-panel partitions, and serious about how prone to the weather the household staying inside would have been. Pinckney wrapped her arms tight round her chest. “That right there was just gut-wrenching,” she stated. “It makes it more real.”

The visceral expertise they’d is exactly the purpose, Stevenson advised me. When we met that night on the EJI workplace, Stevenson stated that the objective of the websites is to pressure guests to confront the violence of the previous with out the counterweight of a extra uplifting narrative to assuage their misery. The websites had been constructed with the goal of not repeating the triumphant progress narrative present in another civil-rights museums, which, as he put it, “would rather tell a story of achievement than a story of continuing struggle.”

“I love those museums,” Stevenson stated. “But if people are allowed to walk out thinking, Oh, isn’t that great that we had that civil-rights movement, and that took care of racism in America, that ended the struggle over voting rights, that ended the struggle over integration and access—if we do that, then we’re undermining the effort to achieve racial justice.” Many civil-rights museums depend on sources from state and federal governments, and Stevenson wonders if a few of them really feel stress to inform a narrative that can fulfill these funders.

For many guests, the EJI museums have grow to be a website of pilgrimage, which has made them a serious driver of tourism to Alabama. The museums are persistently one of many two most-popular paid points of interest within the state (the opposite is the U.S. Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville), and so they obtain about 500,000 guests annually. “Eight hotels have been built in this city since we’ve opened, and airports have record levels,” Stevenson advised me.

Another Black-history museum that serves as a website of pilgrimage is the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., which opened two years previous to the Legacy Museum. Stevenson stated that the Smithsonian museum is a vital presence on the National Mall, and that it’s extra complete than every other museum on Black life within the nation. He worries, nonetheless, that it, too, can enable some guests to depart with an incorrect impression of unalloyed triumph. This is partly, he believes, the results of how the museum was designed. Because its major sections on the oppression and violence that Black individuals had been subjected to throughout the Middle Passage, slavery, and Jim Crow are under the museum’s street-level entrance—whereas the tradition reveals are upstairs—the historical past exhibitions are successfully non-compulsory for guests.

According to museum staff Stevenson has spoken with, this design selection poses an academic problem. “They have a lot of school kids and a lot of groups that come in, and they get in the elevator and they go straight to the upper floors. They want to see Michael Jackson’s coat, and Michael Jordan’s shoe, and B. B. King’s guitar, and then they want to see the stuff on Obama, and then they want to go have a meal,” Stevenson stated. In Montgomery, he defined, “it was important to create a narrative journey where you don’t have the option to avoid the hard stuff.”

Still, the laborious stuff is a sufficiently big a part of the Smithsonian’s providing to guests that in August, the Trump administration announced it will be endeavor a evaluate of the establishment and demanded that the Smithsonian flip over troves of paperwork together with a list of all everlasting holdings, all inside communications related to the approval of exhibitions and paintings, and data concerning 250th-anniversary programming. Per week later, on social media, the president castigated the Smithsonian museums for supposedly having an undue concentrate on “how horrible our Country is, how bad Slavery was, and how unaccomplished the downtrodden have been.”

Stevenson insists that the objective of the Legacy Museum is to not current Alabama as irredeemably racist or perpetually entrapped by its previous. Alabama is a state that he loves. It is his house. He believes it may be completely different sooner or later, however not if individuals flip away from the previous. “I don’t think slavery should define Alabama,” he stated. “And if we have the courage to talk about it honestly, it won’t. But we can’t not talk about it and have a proper understanding of who we are.”

At the Legacy Museum, which is constructed on the location of a cotton warehouse the place enslaved individuals had been as soon as compelled to work, a few of the first gadgets you encounter are clay sculptures depicting the heads of captured Africans rising from the earth, many with chains round their necks, as digital ocean waves crash on screens behind them.

Through detailed explanations of the position that slavery performed in each area of early America, you study that Delaware handed a legislation prohibiting free Black individuals from transferring to the state. You study that in 1730, virtually half of all white residents of New York personally owned an enslaved particular person. You study that by the mid-18th century, enslaved individuals made up 70 % of Charleston’s inhabitants.

In the following room, ghostlike figures projected onto the partitions sing in re-created slave pens. I stood subsequent to a person and his younger daughter within the lengthy corridor lined with cages as we watched a phantom lady sing the refrain of a haunting Negro non secular. The woman leaned into her father’s aspect and wrapped her arms round his waist as he held one hand on her shoulder.

After the Legacy Museum’s sequence of reveals on slavery, guests encounter a piece that focuses on how the many years following emancipation had been much less a interval of unfettered upward mobility for Black Americans than considered one of widespread, sustained racial terror—which regularly got here within the type of lynchings. One of probably the most affecting shows is a wall lined with a whole bunch of jars of soil excavated from websites of lynchings throughout the nation. As I walked by the jars, I used to be struck by how the colour and texture of the soil in every one was completely different.

The soil from the location of Will Archer’s lynching in Carrollton, Alabama, on September 14, 1893, was cinnamon-red and gravelly.

The soil from the location of Marshall Boston’s lynching in Frankfort, Kentucky, on August 15, 1894, was gentle brown and rocky.

The soil from the location of Odis Price’s lynching in Perry, Florida, on August 9, 1938, was black and effective as sand.

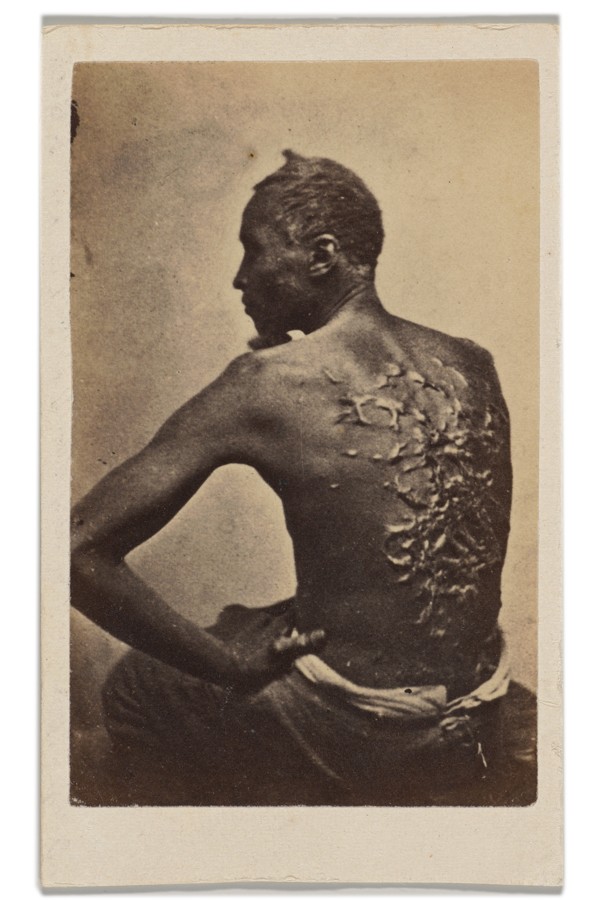

One of the Legacy Museum’s partitions reveals a floor-to-ceiling picture of the notorious “Scourged Back” {photograph}, which depicts the horrifyingly scarred again of a previously enslaved man named Peter who had obtained violent beatings. It was taken and printed within the spring of 1863, within the midst of the Civil War and never lengthy after the Emancipation Proclamation. The picture first circulated in northern cities within the type of small prints often called cartes de visite. When Harper’s Magazine printed it in its July 4 problem, many Americans noticed, for the primary time, the bodily violence wrought by slavery. The {photograph} boosted the abolitionist trigger and challenged the widespread notion that slavery had been a benevolent and mild establishment. Since then, it has grow to be one of many defining pictures of the brutality of enslavement, and has appeared in numerous textbooks, museums, and magazines.

The picture’s presence within the Legacy Museum was notably conspicuous at this second. In September, The Washington Post reported that the identical {photograph} had been faraway from a nationwide park in accordance with a Trump-issued executive order.

Less than a mile away from the Legacy Museum is the First White House of the Confederacy, the place Jefferson Davis and his household lived within the breakaway nation’s earliest days. This White House receives substantial funding from the state of Alabama, and its mission is codified in Alabama state law: “the preservation of Confederate relics and as a reminder for all time of how pure and great were southern statesmen and southern valor.” In 2023, the Associated Press reported that individuals who visited the museum, together with 1000’s of Alabama schoolchildren, were taught that President Davis had led a “heroic resistance” within the “war for southern independence” and was “held by his Negroes in genuine affection as well as highest esteem.”

“When I moved to Montgomery in the ’80s, there were 59 markers and monuments to the Confederacy in the city,” Stevenson advised me. And regardless of Montgomery being among the many most distinguished slave-trading cities in America main as much as the Civil War, “you could not find the word slave, slavery, or enslavement anywhere in the city landscape.”

I requested Stevenson if he thought the United States ought to have a public, nationwide museum, along with the Smithsonian’s NMAAHC, devoted particularly to slavery, or if it was higher to have privately funded establishments just like the Legacy Museum concentrate on that historical past. He paused and thought of the query.

“I’m not sure we’re ready for a state-sanctioned truth telling about the history of slavery,” he stated. “We can have a state-sanctioned space, but I don’t know why we would expect it to be a truth-telling space.” He pointed his finger down on the desk. “Because the reality is we’re not yet at the point where, some would say, it’s in the state’s interest to be truthful about this history, so it would take a lot to get that truth to come through.”

Touring the Legacy Museum that afternoon, I’d seen a Black household with three youngsters standing in a protracted hallway that outlined the chronology of Black life in America. The two older siblings ambled from one picture and caption to the following, whereas the youngest, a boy of about 7 years previous, stood along with his dad and mom and skim the captions out loud as his mom helped him via the phrases he couldn’t pronounce. They got here to a picture of a younger white boy, about the identical age because the Black boy, standing beneath the dangling toes of a Black man who had been lynched from a tree. The man’s face was cropped out of the {photograph}. The boy within the museum locked eyes with the boy within the picture. I heard his dad and mom inform him that generally youngsters attended lynchings as effectively. The father stroked the highest of his son’s head, and so they walked on.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you possibly can go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/2026/01/slavery-museums-black-history-lynching/685660/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us