This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/cut-gems-natural-history-museum-geology-photography-schechter/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

Asha Schechter paperwork the expertise of retouching treasured gems, in an essay from LARB Quarterly no. 47: ‘Security.’

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F5a%20Indicolite%20elbaite-1.jpg)

Did you realize LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes day by day with no paywall as a part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and fascinating writing on each facet of literature, tradition, and the humanities freely accessible to the general public. Help us proceed this work together with your tax-deductible donation as we speak!

This essay is a preview of the LARB Quarterly, no. 47: Security. Become a member for extra fiction, essays, criticism, poetry, and artwork from this problem—plus the following 4 problems with the Quarterly in print.

¤

IN JANUARY 2020, I used to be introduced on to a undertaking on the American Museum of Natural History in New York. They have been updating the Allison and Roberto Mignone Halls of Gems and Minerals and, as a part of this course of, rephotographing every thing within the gem assortment. The exhibition design would function digital screens with photographs of the gems, many smaller than a dime, permitting guests to faucet the gems on screens to see particulars invisible to the bare eye, pinching to zoom within the method to which we’ve got change into accustomed. My pal Cassandra Jenkins had been retouching these new images of the gems for 9 months when she reached out to ask if I’d be accessible to work on the undertaking. She might solely do it for 20 hours per week, she stated, as a result of she additionally labored as a musician and since retouching photographs of gems was so tedious that your eyes might solely deal with concentrating that carefully on the display for therefore lengthy. There have been 6,000 photographs of gems, she defined, photographed from numerous angles, and so they had many extra to retouch, with the reopening scheduled for the top of the yr. We had labored collectively years earlier, within the picture division at The New Yorker, however I used to be now making artwork and adjuncting as a images teacher at just a few schools, and Cassandra was engaged on her second solo album. Both of us wanted these sorts of gig jobs to complement our revenue.

Before I used to be employed, I needed to audition. I used to be given 5 gems to retouch and a few steering from Cassandra:

A short be aware on getting began: an enormous a part of this retouching course of is selecting which components of every picture want retouching, and the way far to go together with the retouching. I all the time attempt to strike a stability of expediting the method and retaining the integrity of the gems. Examples of widespread issues embrace: reflections of catalog numbers, rulers, or lighting sources; dents, mud, and scratches; reflections of the mount (generally paper, foam core, and many others.). Occasionally there are white stability changes and every gem is exclusive.

The gems had been photographed in-house by the museum’s images division with a Canon EOS 80D DSLR—an honest digital digicam, however inferior to the medium-format fashions changing into widespread on the time. They have been photographed on a paper background subsequent to a ruler, or generally between two pen caps and the lens cap. It was by no means clear to me why the varied caps have been there; maybe the paper was curling, or perhaps they have been simpler to concentrate on than a gem, or they made for a constant indicator of scale, like the best way individuals {photograph} objects subsequent to a Coke can on eBay. For my audition, I retouched 5 gems: three tourmalines (5, 11, and 57 minutes, respectively), one beryl (29 minutes), and one quartz (62 minutes).

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F1b%20Ruby%20Corundum%20in%20marble.jpg)

Ruby corundum in marble. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F1a%20Ruby%20Corundum%20in%20marble.jpg)

Ruby corundum in marble, remaining model. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

What we did was solely step one towards perfecting the pictures. I used to be advised by no means to sharpen something, as sharpening, coloration correction, and silhouetting can be executed by one other group. We have been meant to focus completely on eradicating mud, scratches, and man-made marks from the gems’ surfaces, smoothing out broken edges. We had plenty of latitude in deciding what was acceptable and what was an aberration, particularly with out having the precise object to discuss with. We got folders of photographs of gems with names like Beryl, Birthstones, Fluorite, Jewelry & Adornment, Ornamental and Opaque, Organic and Opal, Rare and Unusual, and Synthetics. Some of those classes are scientific classifications and a few are cultural, or based mostly on the museum’s organizational method to show. To an untrained eye like mine, the gems have been largely outlined by associations: this garnet appears to be like like a Jolly Rancher, sapphire is my birthstone, this one was carved into the form of a camel, and so forth. You don’t actually should know what a garnet usually appears to be like prefer to refine it for digital show.

I used to be given entry to a Dropbox folder and assigned a gaggle of photographs to work on every week or so. Once I bought the cling of it, I’d spend a mean of 10–quarter-hour on every gem, becoming in 8–10 hours per week between educating and dealing in my studio. It was an odd, atomized sort of labor: sitting in Los Angeles, receiving folders of freshly photographed gems from a museum in New York staffed by (very pleasant) individuals I’d most likely by no means meet. My lessons shifted to Zoom in March when COVID-19 hit, and when faculty resulted in June, I used to be logging 20 hours per week retouching gems on one display whereas rewatching True Blood within the background.

In documenting gems for posterity, one encounters traditional images issues, the type I’d focus on with college students in my historical past of images class. What is an goal means of seeing? How do you perceive a 3D object by a picture, or a number of photographs? In my communication with Cassandra, the artwork director, and the in-house photographer, there was a lot dialogue of “the window,” the flat clear heart of a gem that confirmed the paper beneath it. This space is undistorted by the sides minimize into the gemstone, which produce inside reflections of sunshine generally known as “brilliance,” robust and colourful dispersion known as “fire,” and brightly coloured flashes of mirrored gentle referred to as “scintillation.” Photographing the window is like photographing smoke or a raindrop: whereas the sides replicate gentle, and the gem in its entirety makes visible sense due to the connection between the angled cuts and the flat heart, the window can solely be regarded by. The bodily circumstances of the documentation change into embedded within the picture. Before I used to be introduced on, the gems have been being photographed on textured foam, which was inflicting big issues within the window. The pen caps and rulers are cropped out, however the materials on which the gem sits when photographed is eternally current, tinting the window.

This was a mode of images I had by no means actually labored in—the {photograph} as a scientific software, as information, as presumed truth. These remaining photographs are supposed to perform for guests as a sort of microscope, a means for human eyes to understand the depths of coloration, gentle, and eternity these gems comprise however which aren’t seen by squinting right into a show case. In digitally correcting lens aberration, bodily harm, lighting results, and white stability, nonetheless, these photographs change into one thing else—an idealized photographic stand-in for the item, one that can doubtlessly outlive and supplant the bodily factor. One blue-green tourmaline I labored on was chewed up the facet, lacking small chunks from its higher edges. I did a cursory cleanup however left these chunks untouched. In the ultimate picture, that edge had been smoothed out, digitally restored. Treated on this means, the images start to perform editorially slightly than scientifically. They begin to resemble hyperreal meals images, or a kind of “exposés” on retouching our bodies in an unrealistic method. The retouched picture is a fantasy model, an idealized type that now not represents a selected gem however a whole group, an ideal instance of its kind. It shifts from being a portrait of a person specimen to a inventory picture.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F2b%20Elbaite.jpg)

Elbaite. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F2a%20Elbaite.jpg)

Elbaite, remaining model. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

While the first perform of those images is enhancing customer expertise on the museum, additionally they serve a secondary function because the photographic archive of the gathering. That is, every of the images is each a public-facing projection and definitive documentation. It’s arduous to think about that the museum will endeavor to rephotograph all the gem assortment with a greater digicam anytime within the close to future. Perhaps when 3D scanning know-how improves, there will likely be an impetus to breed them that means, however for now, that is the archive. For the needs of documentation and preservation and to assist analysis, collections administration, and training, many museums started photographing their collections within the early Twentieth century. This turned customary apply by the center of the century. Even a retouched high-resolution coloration {photograph} continues to be a extra correct copy than the dingy black-and-white images that comprise most Twentieth-century museum picture archives. (Curiously, MoMA was documenting exhibitions in black and white properly into the Nineties.) But alterations do happen, and the picture shouldn’t be the factor itself. That the photographic data of the Museum of Natural History’s gem assortment are “cleaned up” betrays the hole between object and picture that images is all the time navigating.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F3b%20Elbaite.jpg)

Elbaite. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F3a%20Elbaite.jpg)

Elbaite, remaining model. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

These images aren’t, in different phrases, the proper data Oliver Wendell Holmes wrote about in 1859, 20 years after the invention of images, in an essay in The Atlantic Monthly on stereoscopy:

Form is henceforth divorced from matter. In truth, matter as a visual object is of no nice use any longer, besides because the mould on which type is formed. Give us just a few negatives of a factor value seeing, taken from totally different factors of view, and that’s all we wish of it.

For Holmes, the {photograph} was a mirror of actuality, so exact in its verisimilitude that one might destroy the referent and nothing can be misplaced. “Every conceivable object of Nature and Art,” he predicted, “will soon scale off its surface for us. […] The consequence of this will soon be such an enormous collection of forms that they will have to be classified and arranged in vast libraries, as books are now.” In his 1986 article, “The Body and the Archive,” Allan Sekula describes a Henry Fox Talbot {photograph} of a shelf of china:

Talbot speculates that “should a thief afterwards purloin the treasures—if the mute testimony of the picture were to be produced against him in court—it would certainly be evidence of a novel kind.” Talbot lays declare to a brand new legalistic reality, the reality of an indexical slightly than textual stock. Although this frontal association of objects had its precedents in scientific and technical illustration, a declare is being made right here that will not have been made for a drawing or a descriptive record. Only the {photograph} might start to assert the authorized standing of a visible doc of possession.

One imagines a heist on the corridor of gems: a masked burglar filling little velvet baggage with the treasures of the gathering. All that will stay can be a Dropbox of 25 MB images digitally scraped of their specificities. (“Your honor, that picture couldn’t possibly be the emerald found on my client: it doesn’t show a big scratch.”) Although images started to function proof in courtroom shortly after the invention of the medium, doubt within the veracity of those photographs plagued them from the beginning. In Tome v. Parkersburg Branch Railroad Company, an 1873 case during which photographic enlargements of presumably cast signatures have been launched as proof, the courtroom expressed skepticism concerning the {photograph}’s skill to precisely signify actuality:

Photographers don’t all the time produce actual fac-similes of the objects delineated, and nonetheless indebted we could also be to that stunning science for a lot that’s helpful in addition to decorative, it’s eventually a mimetic artwork, which furnishes solely secondary impressions of the unique, that modify in response to the lights or shadows which prevail while being taken.

Eighty-six years after Holmes fashioned his concept of the proper copy, André Bazin, in “The Ontology of the Photographic Image” (tr. Hugh Gray, 1960) demonstrated an nearly spiritual perception within the {photograph}’s skill to soak up a chunk of actuality:

Only a photographic lens can provide us the sort of picture of the item that’s able to satisfying the deep want man has to substitute for it one thing greater than a mere approximation, a sort of decal or switch. The photographic picture is the item itself, the item free of the situations of time and house that govern it. No matter how fuzzy, distorted, or discolored, regardless of how missing, in documentary worth the picture could also be, it shares, by advantage of the very strategy of its changing into, the being of the mannequin of which it’s the copy.

For Bazin, the imprint of mirrored gentle an object makes on movie is the elemental nature of the photographic picture. His shouldn’t be the proper reproduction Holmes imagines, however a brand new image haunted by its encounter with the factor it depicts, even when that depiction falls properly quick or diverges from our notion of actuality. The twinkling gem images would have delighted Bazin, as they fulfill his concept of “the creation of an ideal world in the likeness of the real, with its own temporal destiny.” In his framework, the pictures can fortunately outlast the gems themselves.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F4b%20Rose%20Quartz.jpg)

Rose quartz. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F4a%20Rose%20Quartz.jpg)

Rose quartz, remaining model. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

When I started retouching gems, I had, for 4 years, been making artworks with digital 3D modeling output as 2D prints on adhesive vinyl. Initially I had used inventory fashions, however at this level I turned towards making replicas of actual objects. I used to be engaged on photographs of rubbish, and the commonest rubbish in my studio then consisted of pamplemousse LaCroix cans. I despatched a 3D modeler photographs of a crumpled can, from which he constructed a wireframe reproduction in Autodesk 3ds Max. I painstakingly recreated the LaCroix can graphics in Photoshop to make use of as a “digital skin.” He then “wrapped” this pores and skin across the 3D mannequin, positioned it right into a digital atmosphere, and output high-resolution 2D photographs from quite a lot of angles. This work, which initially in my thoughts was particular, referring to that exact can, was understandably perceived as generic, and individuals who encountered it in Los Angeles learn it as a satire of burgeoning beverage developments. That specific can was subsumed right into a generic illustration of a sort.

I continued making this sort of work with objects I owned that exhibited proof of use: a clock introduced from Shanghai by a pal, which a fly had died within; my smudged Berkey water filter; a bag of peppercorns gifted by an ex; a dustpan filled with my cat’s fur. These works type a nebulous archive—they aren’t images however they discuss with actual issues, and their hyper-articulated surfaces and exaggerated scale produce such heightened element that they exceed their referents in legibility and presence. Through their extra they depict the change that happens within the translation of object to picture.

Scale is, after all, central to our fascination with gems: they’re tiny and mesmerizing and generally very precious. People have imagined vastly enlarging gems or penetrating their dense interiors lengthy earlier than the Museum of Natural History even thought-about endeavor this undertaking. In George Sand’s Laura: A Journey into the Crystal (1864; tr. Sue Dyson, 2004), a lovestruck younger man has hallucinatory visions of coming into a gem, the place he discovers a fantastical panorama:

I used to be with Laura within the centre of the amethyst geode which graced the glass case within the mineralogical gallery; however what as much as then I had taken blindly and on the religion of others for a block of hole flint, the dimensions of a melon minimize in half and lined inside with prismatic crystals of irregular dimension and groupings, was in actuality a hoop of tall mountains enclosing an immense basin stuffed with steep hills bristling with needles of violet quartz, the smallest of which could have exceeded the dome of St Peter’s in Rome each in quantity and in peak.

Later within the novel, Laura’s eccentric uncle tells the protagonist, “Crystal […] is not what the common person thinks; it is a mysterious mirror which, at a given moment, received the imprint and reflected the image of a great spectacle. This spectacle was that of the vitrification of our planet.” Inside every crystal is a bodily world and a temporal one. This is scientifically confirmed by a plaque on the Museum of Natural History that states, “We are now recording: Garnets can engulf other minerals as inclusions, which become a kind of time capsule. They can also have compositional zoning, where the core and exterior have different chemical compositions, showing how conditions changed over time.” The gem incorporates an indexical imprint of the previous simply because the {photograph} does, an nearly literal instance of the method Bazin imagined. The gems in Laura, written shortly after the invention of the daguerreotype, comprise microscopic worlds the best way these images did. Art conservator Ralph Wiegandt (as paraphrased by science reporter Stephen Ornes) explains that “well-made daguerreotypes can be enlarged 20–30 times and still reveal minute details of their subjects—a resolution that, today, would require a 140,000-megapixel digital camera,” dwarfing the 24.2-megapixel sensor on the digicam used for the museum’s gem images.

Camera lenses themselves are generally made with fluorite or different crystals (by the way, we retouched 130 photographs of fluorite). Fluorite reduces chromatic aberration within the {photograph}, a delicate fringing of coloration typically mentioned on boards about telephoto lenses, perhaps illustrated with a crop of a fowl’s wing exhibiting a delicate hue on the sting. It bends gentle again into form, lowering these halos higher than glass does. In their pure state, fluorite crystals are by no means giant sufficient to make a digicam lens, so within the Nineteen Sixties, Canon developed an artificial model that could possibly be formed to the suitable dimensions and was freed from the impurities that give fluorite a inexperienced or purple tint. Drained of its personal coloration, the artificial model reduces aberrant coloration within the photographs it helps produce. A gem created to not be checked out, however regarded by.

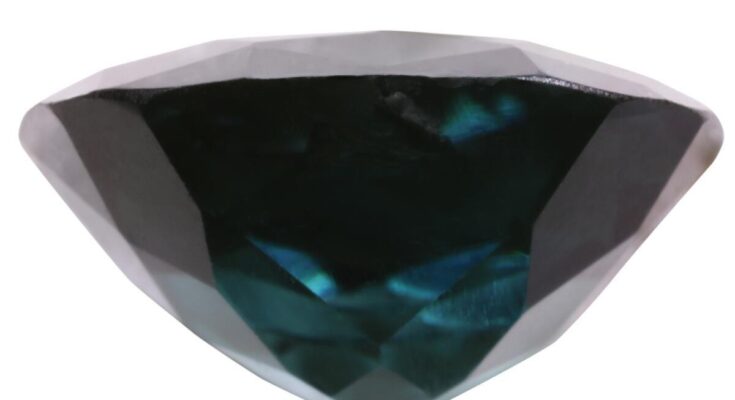

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F5b%20Indicolite%20Elbaite.jpg)

Indicolite elbaite. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

:quality(75)/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.lareviewofbooks.org%2Fuploads%2F5a%20Indicolite%20Elbaite.jpg)

Indicolite elbaite, remaining model. © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

A journey into the inside of a gem is depicted nearly actually in The Invisible Photograph: Part 1 (Underground), a 2014 documentary quick produced by Arthur Ou and Tina Kukielski as a part of a Carnegie Museum of Art initiative. It takes the viewer into Iron Mountain National Underground Storage Facility, a repurposed limestone mine in Pennsylvania that homes the 11 million images within the Bettmann Archive (owned by Corbis, Bill Gates’s inventory images firm, on the time of filming). Unlike a museum picture archive, Bettmann is business in nature; slightly than documenting a discrete assortment, it amasses footage of every thing, licensing them for a charge. The inside partitions are craggy white limestone: it appears to be like like Superman’s Fortress of Solitude, the Snow White journey at Disneyland, or the within of a gem. Part 1 (Underground) tells the story of Otto Bettmann fleeing Nazi Germany with just a few crates of images and beginning the images archive within the United States that ultimately moved to this facility, constructed for splendid storage situations. Employees have fun the virtues of the “capture form,” the best way negatives protect the world with a sort of purity, unaltered by printing methods. Bethany Boarts, the digital imaging coordinator at Iron Mountain, presciently predicts a return to the usage of movie. Showing this video to my images lessons by the 2010s, I’d scoff at this, however Boarts was confirmed proper by a Zoomer fascination with analog images. (The girl at Bleeker Digital, the place I course of my movie, tells me that a lot of the twentysomethings by no means really decide up their negatives, solely needing scans giant sufficient to submit. The retailer’s dumpster have to be a particular archive.)

In January 2016, Corbis introduced that it had bought its picture licensing companies to Unity Glory International, an affiliate of Visual China Group. VCG, in flip, licensed the picture assortment to Corbis’s historic rival, Getty Images. Despite this modification in possession, the archive has stayed put. The mine doesn’t simply home a historic file; it is usually a temple to the {photograph} as an object, containing shelf after shelf of negatives, transparencies, and prints. In the documentary, archivist Henry Wilhelm admits that he had fears about Gates’s buy of the archive: “Bill Gates is the ultimate digital guy […] he’s gonna digitize the whole collection and throw away the originals and it’s over”—a Twenty first-century Oliver Wendell Holmes. But in doing the other, Gates demonstrated a perception within the auratic nature of the unique materials—a Bazin-like mindset—and the potential instability of the digital. Wilhelm, a captivating character who maintains an internet site with a downloadable 3,213-page PDF on the archival high quality of photographic supplies, explains that, in his youth, he volunteered with the Peace Corps within the Bolivian rainforest, which was “like an accelerated aging chamber for photographs.” The mine, then again, is saved at a perfect temperature, during which the gathering degrades 500 occasions slower than in its earlier residence in Manhattan.

The archival impulse mixes the will to dwell eternally with the tragic recognition that each one the cautious preservation at greatest merely slows down inevitable decay; every thing returns to mud. Probably the identical inspiration lies behind the companies supplied by an organization like EverDear. For as little as $995, you may make the ashes of a cherished one (human or pet) right into a diamond, reworking their physique into what the corporate calls “the Ultimate Expression of Love.”

¤

All photographs © American Museum of Natural History, New York.

LARB Contributor

Asha Schechter is an artist, author, and writer. His press, Apogee Graphics, is predicated out of the Bonaventure Hotel in Los Angeles.

Share

LARB Staff Recommendations

-

Nathan Crompton interviews Andrew Witt about documentary as type and photographing L.A. in a web based launch from LARB Quarterly no. 45: “Submission.”

-

Brittany Menjivar stuffs herself with trivia on the artwork of museum dioramas.

Did you realize LARB is a reader-supported nonprofit?

LARB publishes day by day with no paywall as a part of our mission to make rigorous, incisive, and fascinating writing on each facet of literature, tradition, and the humanities freely accessible to the general public. Help us proceed this work together with your tax-deductible donation as we speak!

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its unique location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://lareviewofbooks.org/article/cut-gems-natural-history-museum-geology-photography-schechter/

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us