This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20260216-10-early-photographic-fakes-that-trick-the-eye

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us

1. Daydream (c 1870–1890), nameless

Two realities collide on this Nineteenth-Century carte de visite that was most probably bought to be collected and traded. Cartes de visite had been small mass-produced prints mounted on card, and had been very fashionable within the Victorian period. In this one we see the current: a girl and her companion each with the instruments of their trades; and an imagined future: her daydream of turning into a mom. The picture, explains Rooseboom, was “a darkroom trick”, achieved by shielding a part of the photographic paper from the sunshine after which including a second destructive to it later. Such photographs took images into a brand new dimension, suggesting the innermost ideas of their topics, and paving the way in which for the comedian strips of the long run with their speech bubbles and thought clouds.

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

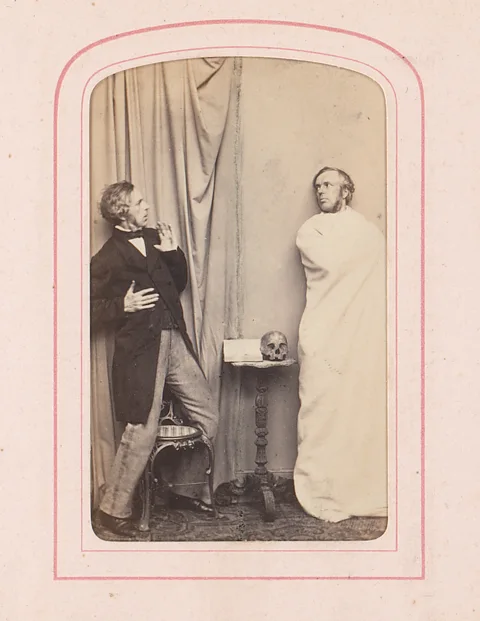

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum2. Man startled by his personal reflection (c 1870–1880), Leonard de Koningh

In this comical memento mori, the place a person comes nose to nose along with his ghost, the painter and photographer Leonard de Koningh uncovered simply half of the photographic plate, then had the topic undertake a distinct pose earlier than exposing the opposite half. Photography might need been a comparatively new artwork, however the transition between the 2 photographs is imperceptible. “It’s like a magician,” marvels Rooseboom. “You know you are being tricked, but you don’t know how the photographer does it.” Quoting Oscar Gustave Rejlander, a trailblazer for one of these composite printing, the photographer Robert Sobieszek (1943-2005) stated: “This manner of working led not to falsehood but to truth. An image made by a single negative [claimed Rejlander] ‘is not true, nor will it ever be so – the focus cannot be everywhere’.”

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum

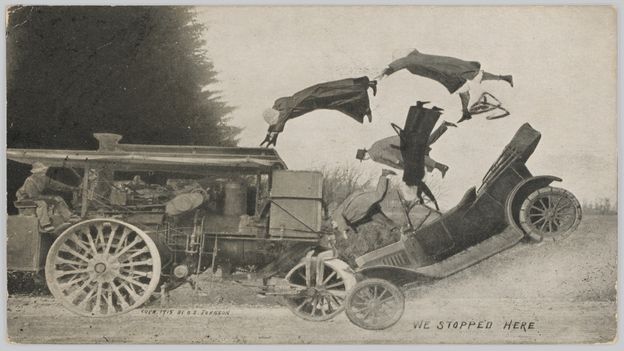

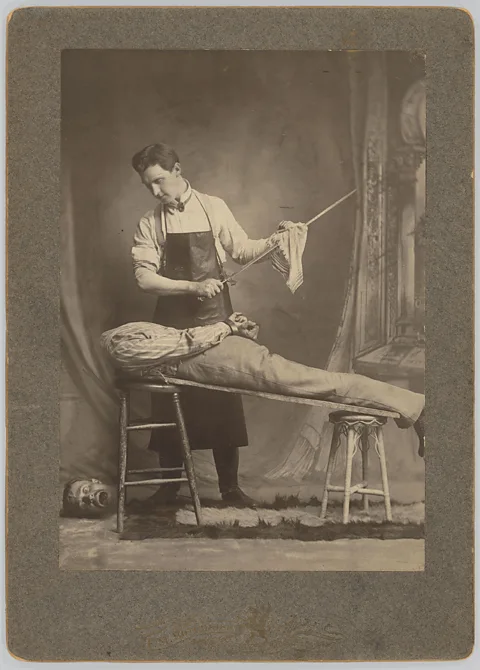

Courtesy of the Rijksmuseum3. Decapitation (c 1880–1900), FM Hotchkiss

“We still expect photography to bring the truth, but this idea only really emerged from the illustrated magazines of the 1930s in order to inform readers how things worked elsewhere in the world,” says Rooseboom. Until then, the artistic freedom to change the picture was unchallenged. “Anything possible would be tried out and produced,” he says. “There was no ethical restraint on producing non-realistic images. No-one would forbid you from doing this.” Removing and transferring somebody’s head, for instance, introduced the photographer with a delightful puzzle. In the case of this cupboard card – a method of print mounted on card had taken over from the smaller carte de visite by the Eighties – with its black humour, the artistic mission was extremely profitable. Only the positioning of the curtain, that will have hid the unique head, and a few gentle retouching seen beneath a microscope, supply clues to how the photographer created the deception.

This web page was created programmatically, to learn the article in its authentic location you may go to the hyperlink bellow:

https://www.bbc.com/culture/article/20260216-10-early-photographic-fakes-that-trick-the-eye

and if you wish to take away this text from our website please contact us