This page has been generated automatically; to read the article in its initial setting, you can visit the link below:

https://www.wunc.org/2024-12-28/parker-solar-probe-aims-to-teach-us-more-about-the-sun

and if you wish to remove this post from our site, kindly reach out to us

ANDREW LIMBONG, HOST:

This is what I understand about the sun – it’s enormous, it’s scorching, and if I remain exposed to it for too long, my skin begins to flake. However, there’s an abundance we still lack knowledge about. Thanks to the Parker Solar Probe, we are poised to uncover far more information. This compact spacecraft achieved something unprecedented this week. It approached the sun closer than any other human-crafted object. Nour Rawafi is the principal scientist for NASA’s Parker Solar Probe mission and joins us now. Welcome, Nour.

NOUR RAWAFI: Thank you very much. I appreciate your invitation.

LIMBONG: So, enlighten me about the Parker Solar Probe. What is its purpose, and what is it seeking?

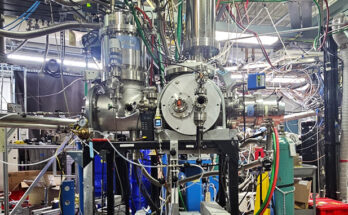

RAWAFI: The Parker Solar Probe is a NASA initiative crafted at Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory, launched in 2018. Its objective is to approach the sun as closely as possible to unravel some of the enigmas surrounding our star. The sun is a magnetized star, highly active, and from time to time, it generates magnificent explosions, such as flares and coronal mass ejections, that influence space weather on Earth. Parker Solar Probe is designed to help us comprehend all these phenomena and beyond, as we navigate an area of space we have not explored prior, with every measurement taken by Parker Solar Probe presenting a potential revelation.

LIMBONG: And why are these revelations significant for NASA?

RAWAFI: They hold substantial importance for numerous reasons. There are billions upon billions of stars in the universe, and we ponder whether life exists elsewhere. To address that, we must grasp the interactions between a star and its planetary system, particularly within the habitable zone akin to Earth. The most effective method for this is to analyze our closest star and understand how it interacts with us here on Earth and in other locations, like Europa or various planets in our solar system.

Moreover, we dwell within the sun’s atmosphere, known as the solar wind, and any activity from the sun can influence us in various ways. For instance, the geomagnetic storms we observed in May and October of this year can impact space technology, such as telecommunication satellites and astronauts. Thus, to live in harmony with our star, we need to comprehend its workings. This understanding enables us to forecast its actions at any moment and undertake appropriate measures to mitigate its impacts.

LIMBONG: Okay. Let’s discuss how you accomplished this. How did NASA succeed in getting so close without incinerating the craft?

RAWAFI: This is where the significance of this achievement truly lies. Scientists began contemplating missions like the Parker Solar Probe back in 1958. NASA attempted to realize this mission four or five times since the mid-’70s, but none of these efforts succeeded for a straightforward reason: we lacked the requisite technology to safely operate a spacecraft very close to the sun’s atmosphere. In 2001, NASA tasked the Applied Physics Lab with researching materials for a heat shield. It took about six years to identify the right material, but we were confident we could construct it and that it would suit the spacecraft.

You wouldn’t believe it—the heat shield of Parker Solar Probe is fundamentally a piece of carbon foam, but it’s a unique one. When Parker Solar Probe approached the sun this Tuesday, we estimated that the side of the heat shield facing the sun would endure temperatures ranging between 1,800 and 1,900 degrees Fahrenheit.

LIMBONG: That’s quite extreme.

RAWAFI: Indeed. It’s exceedingly hot.

LIMBONG: Yes.

RAWAFI: The remarkable thing—if I may call it magic, though it’s engineering—is that a yard behind it, the temperature is nearly room temperature, where the main body of the spacecraft and most of the instruments are situated. This is how we achieved our mission, but it took us a significant amount of time. Now, Parker Solar Probe is executing remarkably well around the sun.

LIMBONG: As I understand it, during this mission, there was a phase when scientists could not communicate with the probe, correct? You lost contact with it on the 24th, just as it was nearing the sun?

RAWAFI: Correct. On its inbound journey, we received a signal we refer to as a beacon tone on December 19, indicating that the spacecraft was operational and prepared to follow its flight path. However, during the subsequent days, leading to the closest approach, we had absolutely no information regarding Parker Solar Probe’s condition. We had to wait until Friday, when Parker Solar Probe reemerged on the opposite side, to send us a signal confirming that everything was satisfactory. The amusing part is that this time, Parker Solar Probe transmitted that signal four times—as if to reassure us, “Hey, don’t worry.”

LIMBONG: (Laughter) “I’m here. I’m here.”

RAWAFI: Everything is under control.

LIMBONG: What was that waiting period like, during which you couldn’t receive any updates, and then when communication was restored?

RAWAFI: I believe the team’s sentiment was one of confidence that everything would function smoothly. Personally, however, on the day we awaited the signal on Friday, I felt a bit anxious.

LIMBONG: That’s when the perspiration started (laughter).

RAWAFI: Well, you know, as scientists, we are rarely at ease.

LIMBONG: (Laughter).

RAWAFI: Now that we know everything went successfully, we eagerly anticipate the incoming data to discover what it holds.

LIMBONG: So, regarding that data, it should be arriving soon, correct? What do you anticipate…

RAWAFI: Yes.

LIMBONG: …to uncover?

RAWAFI: In the third week of January, we will commence receiving the scientific data. Every three months, we obtain a fresh batch of information. With each new orbit, we also acquire a new set of data. Thus, as scientists, we feel like spoiled children. Every three months, we dive into a new collection of fresh data, and we are excitedly exploring. Honestly, we can’t predict what we’ll discover in that data. If you were to ask me, I’m hopeful that the Parker Solar Probe will deliver us the greatest present ever. After all, it’s the close of the year, with Christmas and the New Year approaching. It’s the season for gift-giving, and I genuinely hope Parker Solar Probe has a splendid gift for us this time.

LIMBONG: That was Nour Rawafi, the principal scientist for NASA’s Parker Solar Probe initiative. Nour, thank you very much.

RAWAFI: Thank you very much. It’s been a pleasure.

(SOUNDBITE OF MUSIC) Transcript provided by NPR, Copyright NPR.

NPR transcripts are generated under tight deadlines by an NPR contractor. This text may not be in its ultimate form and is subject to future updates or revisions. The accuracy and availability may fluctuate. The definitive record of NPR’s programming resides in the audio format.

This page has been generated automatically; to read the article in its initial setting, you can visit the link below:

https://www.wunc.org/2024-12-28/parker-solar-probe-aims-to-teach-us-more-about-the-sun

and if you wish to remove this post from our site, kindly reach out to us