This webpage was generated automatically. To access the article in its original source, you can follow the link below:

https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2024/12/gaming-notes-6

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website, please get in touch with us

Last week, my Steam Replay was released, prompting me to compile another of these entries before the year concludes. I don’t utilize Spotify, so the yearly excitement surrounding Spotify Wrapped generally goes unnoticed by me, but Steam Replay often reveals some unexpected insights. For instance: despite not considering myself an enthusiastic gamer (and being able to—and this year, have—gone several months without engaging in any gaming), it turns out I actually play a significant number of games. I am even well above the Steam average in terms of games played and achievements earned.

A clear explanation for this enigma exists: I have little interest in the expansive, open-world games that can easily consume hundreds of hours, such as the latest Baldur’s Gate or Star Wars extravaganzas. I typically enjoy smaller, more concise games. Once a game captures my attention, I tend to dive into it obsessively, aiming for every possible achievement. As a result, I have played more games and unlocked more achievements. However, I still don’t perceive gaming as a substantial part of my leisure activities this year. This last assortment of games feels more like a mixed bag than what a dedicated gamer would typically engage with.

Before delving into the reviews, there are a few exciting updates in the gaming world. Two titles I’ve previously mentioned have received significant patches. Slay the Princess has introduced The Pristine Cut, featuring new story arcs and a fresh ending to an already intricately branching narrative. I haven’t tried it yet—honestly, navigating the numerous story paths in the original game was somewhat overwhelming, and I’m unsure I have the energy to explore what’s new. However, if you found my previous insights into the game intriguing, the current version available is deemed the definitive one by the developers, Black Tabby Games. Meanwhile, Potion Craft: Alchemist Simulator has rolled out a major quality of life enhancement that modifies significant gameplay elements, allowing players to manage the ingredients cultivated in their garden and completely revamping the game’s skill tree. Since my main critique of Potion Craft when I wrote about it last year revolved around quality of life issues, I was keen to observe the impact of these modifications, and I must say my gameplay experience has seen a significant improvement. Consider my previous lukewarm review upgraded.

Finally, Swedish developers Something We Made have announced a sequel to their delightful photography-and-exploration game Toem. The game’s concept was straightforward yet engaging enough that I can effortlessly envision a sequel being just as enjoyable as the original. The tentative release date is sometime in 2026, but I’ve already added Toem 2 to my wishlist.

As always, consider this post as an invitation to share your gaming experiences. What was the best game you played in 2024? What are your expectations for 2025? Are you planning any gaming sessions during the holidays?

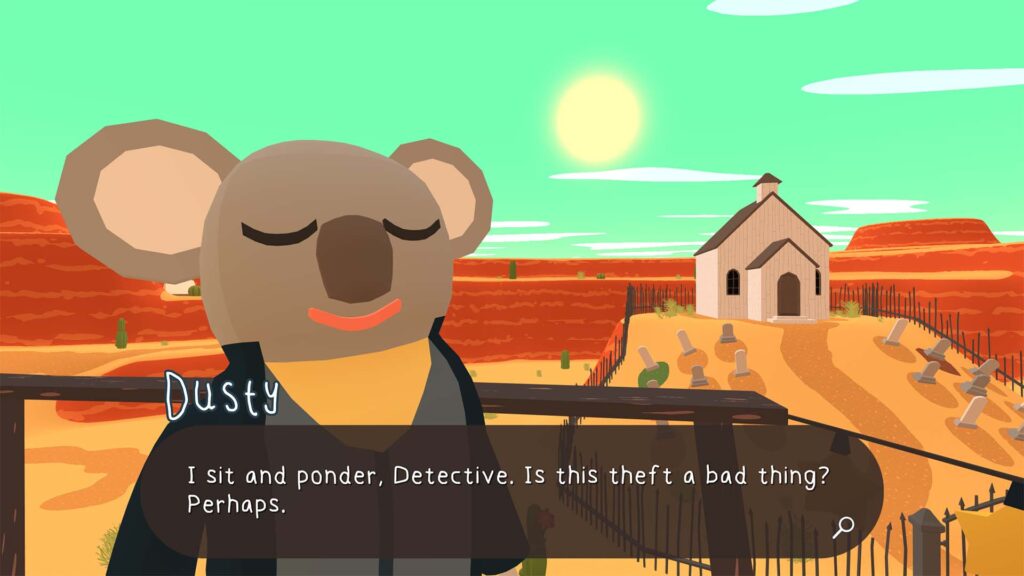

Frog Detective 1: The Haunted Island (2018)

Frog Detective 2: The Case of the Invisible Wizard (2019)

Frog Detective 3: Corruption in Cowboy County (2022)

Many of the games I mention in these articles are detective games, primarily because they blend two elements I appreciate in gaming: puzzles and an engaging narrative. Right from the start, I have to clarify that Australian developer Worm Club’s Frog Detective trilogy does not precisely fulfill either of those criteria. You assume the role of the eponymous detective, who is sent in each title to uncover a different mystery: what is causing the odd night noises on a desolate island? who sabotaged the planned welcome gathering for a new occupant in an upscale area? who made off with all the hats in an Old West town? However, the methods of solving these mysteries are more aligned with scavenger hunts. You must gather a specific number of cactus flowers for a stew to present to a town resident in exchange for a painting to give to another resident, and so forth. (In terms of puzzles, the Frog Detective games are accessible for children, although they carry a deliberately childish tone that might resonate more with adults.) The resolutions to the mysteries themselves are often absurdly simple, frequently relying on misunderstandings or inching toward surrealism. For example, the reason behind the nighttime disturbances on the haunted island turns out to be a chicken preparing for a dance competition, which has opted to conduct her practice sessions in a conveniently located cave.

This delightful absurdity is where the true charm of the Frog Detective games resides. Every character in these games displays a monomaniacal and overly literal demeanor—when Frog Detective is handed a notebook to keep his case notes at the start of the second game, the individual giving it insists he can’t leave until he decorates it with stickers—yet they maintain a remarkably stoic attitude toward matters of ego and self-perception. Frog Detective—who never ventures anywhere without his reliable magnifying glass—cheerfully confesses that he is…

only the second-most skilled investigator in his division, constantly reminding his overseer (whose name is “Supervisor”) that he is being assigned tasks since the leading officer, Lobster Cop, is occupied with more significant inquiries. Conversely, when suspicion is cast upon Frog Detective regarding the hat theft, everyone concurs that he’s the prime suspect, as the contour of his head must render him an unyielding hat-detester. Even the game’s visuals, which are composed of large, uneven blobs of color resembling those cut out of construction paper by a kindergartener, seem to partake in the humor.

It’s the kind of comedy that can grow tiresome rather quickly, but fortunately, each of the Frog Detective games only endures for an hour or two, and along the journey, they manage to insert a few sharp critiques at the entire copaganda narrative—when the caper of hats emerges as an actual offense rather than, as seen in the two earlier games, a misunderstanding, the entire cast is astonished to learn that “crime is genuine?!” At the very least, the Frog Detective games, in all their intentional inelegance and equally purposeful absurdity, are evidently a labor of passion crafted by individuals who are set on being peculiar, and although they wouldn’t be my primary suggestion for a gaming experience, I must acknowledge them for that. (All three Frog Detective games have been released collectively under the title Frog Detective: The Entire Mystery.)

Firmament (2023)

In my previous games summary, I enthusiastically praised Cyan’s remaster—which was effectively a complete reimagining—of their finest game Riven. This brought to mind that there is a Cyan title I have yet to experience, leading me to now render the jarring verdict that Firmament is among Cyan’s less appealing products. The game begins in a sufficiently familiar manner. You awaken as a faceless, emotionless first-person character in an odd, intricate setting filled with levers to manipulate, routes to clear, and devices to activate, and must discern what transpired here and what actions you can take. Two aspects differentiate Firmament from this established mold. Firstly, you are joined by recordings of an unnamed woman, who clarifies that you are a Keeper tasked with tending to the Realms, and that following some undefined crisis, you need to prepare them for the Embrace. (There are numerous Capitalized Nouns in Firmament.) Secondly, you are promptly equipped with an Adjunct (see?), a sort of multifunctional tool that fits over your arm, enabling you to operate various terminals that manage doors, bridges, carts, engines, and many other devices scattered across the game’s realms. As you explore the suspiciously vacant Realms, your guide’s narrative unveils a tale of maltreatment, exploitation, and treachery.

The issue with this setup is that it’s all tremendously dull. For one reason, visually. Firmament presents stunning graphical capabilities, yet the landscapes and settings they depict are all rather monotonous and indistinct. A magnificent, snowy mountain range looks breathtaking during your initial passage through it, marveling at the intricacies on each rock and snowbank. A few minutes later, as you realize that generic natural scenery is the entirety of what you’ll encounter, it begins to feel rather disheartening. The same applies to the structures you come across, like the Spire (there we go again) whose allure your guide praises, but which, in reality, is merely a jumble of different shapes lumped together. Cyan games are recognized for the depth of thought dedicated to their environments—the architectural and decorative touches on every edifice, the scattered relics that imply how these spaces were utilized by the individuals who inhabited them. All of that is missing in Firmament, as is a sense of those people—fans of Cyan will be accustomed to an abundance of documentary evidence and environmental storytelling, yet in this game, these elements are exceedingly sparse. The outcome is that the excitement of discovery that accompanies most Cyan games, the emotional attachment one develops with their environments and characters, is nearly entirely absent. (Following the release of Firmament, Cyan faced criticism for employing AI to generate in-game texts and documents, but if this is what results from those tools, I’d argue Firmament serves as a strong endorsement for the irreplaceability of human artists.)

This same monotony plagues Firmament‘s puzzles, which primarily revolve around deciphering industrial processes: activating a steam engine, or providing precursor materials for a chemical facility. There are some interesting moments along the way—the player gets to ride a block of ice down a chute, or don a protective suit and delve into a vat of sulfuric acid to chip away at encrustations obstructing its machinery. However, not a single puzzle in Firmament felt enjoyable, or afforded me a sense of achievement upon solving it (in fact, after a certain stage, I became so drained that I began seeking hints merely to keep things progressing). The enchantment of Cyan games lies in how they draw you into their worlds, immersing you in their logic until the answers to their puzzles become more about comprehending how the world operates than uncovering distinct clues. In Firmament, all that weight of significance is withheld until the game’s ultimate revelation—which, in fairness, is a solid one, and even leverages the players’ assumptions about Cyan games to subvert expectations in certain ways. By the time I reached this moment, however, I was more than prepared for Firmament to conclude.

Paper Trail (2024)

When you distill them to their core elements, there are merely a handful of distinct types of puzzle games. Path-finding games, where players must navigate a character from one end of a game board to another under an increasingly intricate set of rules and restrictions, represent a popular category, and it takes a certain creativity to devise a fresh angle on the concept. British creators Newfangled Games have discovered one such innovation in their newest title, where they conceptualize the game board as a sheet of paper that can be folded over itself, exposing different features on the reverse side that can alter the board’s layout and establish new routes across it. You take control of Paige Turner (get it?), a high school graduate embarking on her journey from home to college, which spans caves, marshes, oceans, towns, and various other environments. The fundamental rules are established swiftly—you can’t fold over a fold or over Paige herself—but akin to any excellent puzzle game, Paper Trail quickly introduces further complexities to its premise—switches that unlock doors or elevate bridges, unusually shaped game boards, or scenarios where folding one section of the board triggers another area to fold as well.

The puzzles are challenging yet reasonable, and like the finest types of brain teasers, they primarily succeed because they compel you to shift your way of thinking, to perceive a game board not as a static component but as something you can manipulate. An in-game hint system is equally effective, indicating the folds necessary to complete each level while omitting other actions—such as where to move Paige and other movable objects—to sustain a level of difficulty. I have previously commented on how the ideal level of challenge for a puzzle game is an exceptionally personal aspect, but in my opinion, Paper Trail strikes an excellent balance. If there is a critique that could be directed at the game, it’s that its narrative, the impetus for Paige’s departure to university, is rather mundane. This isn’t necessarily a deal-breaker in a puzzle game, of course, but especially in the type of puzzle revolving around moving a character from one location to another, having a compelling story about the reasons behind this journey enhances your emotional engagement. The narrative in Paper Trail, which involves disapproving parents and a missing sibling, is clichéd enough that I began to begrudge the time the game dedicated to it. Ultimately, however, this is a minor point in the grand scheme of the game, and the sense of achievement derived from guiding Paige to her goal far outweighs her uninspired motivations for the trip.

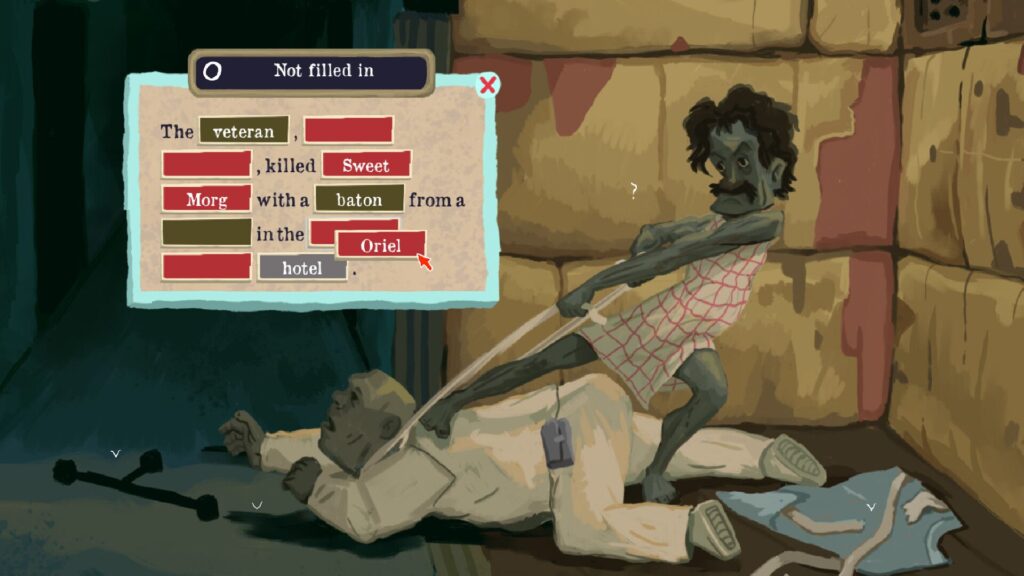

The Rise of the Golden Idol (2024)

There are a pair of 2024 titles that I purchased on their launch day. One is the Riven remake, and the other is Color Gray Games’s follow-up to their charming, addictive 2022 mystery game The Case of the Golden Idol. Both have become my favorite games of the year. This indicates that I am aware of my preferences, but also that the developers have successfully retained what worked well while enhancing it further. Similar to its precursor, Rise of the Golden Idol provides a sequence of vignettes, primarily revolving around murder or other forms of violence—a woman tearfully rakes the soil in her garden, while her home displays undeniable signs of a recent struggle; a crowd scatters from a drive-in cinema after one of the vehicles bursts into flames; an auction is thrown into chaos by a sudden blackout, while in the adjacent room, a security officer is electrocuted. In each situation, the player must investigate—search through people’s pockets, flip through calendars and sticky notes, and combine all that with information from previous segments—to complete puzzle pages identifying who is who, what has transpired, and who is responsible. It’s a pure logic puzzle, dressed up and enhanced by an enticing pulp adventure narrative. The initial Golden Idol title was a historical enigma, where oblivious European explorers, full of their own sense of superiority, got more than they expected when they attempted to tap into the powers of the titular artifact. Rise of the Golden Idol adopts a classic, and utterly captivating, sequel method, where contemporary individuals aim to apply science to ancient enigmas, only for it all to backfire spectacularly.

Color Gray released two DLCs for The Case of the Golden Idol last year, which expanded the narrative and offered more puzzling enjoyment. However, despite my enjoyment of revisiting this game’s universe, I found those mysteries somewhat vexing, inundated with excessive information and overly complicated challenges, necessitating me to perfectly align with the developers’ mindset (once more, this kind of experience is incredibly subjective, but I’ve heard similar sentiments from individuals who are more adept at puzzles than myself). Rise of the Golden Idol offers a substantially smoother experience. The puzzles are more challenging than in the original game, frequently requiring players to piece together information from various time periods while keeping track of the paths of a diverse cast of characters. However, in contrast to the DLCs, this isn’t difficulty for its own sake. The game maintains fairness, and if you focus, the answers often become apparent. The variety of puzzles is also significantly broader—you need to determine which neighbor resides in which unit within an apartment, or identify various exotic birds at a sanctuary, or (in one of my absolute favorite puzzles) interpret a message conveyed through the medium of dance—making the entire experience far more enjoyable. A significant enhancement is that Rise implements considerable improvements to the original game’s interface, which facilitates the puzzle-solving experience, enabling you to concentrate on one inquiry at a time. (Some of these enhancements have also been integrated into The Case of the Golden Idol, which received a massive, free quality-of-life upgrade shortly before Rise’s release.)

None of this, of course, would matter if Rise of the Golden Idol didn’t feature a remarkable narrative, and here too the game surpasses its predecessor, tracing multiple characters across various narrative arcs, each perceiving their small part of the whole while the player becomes increasingly alarmed by what’s unfolding. As the oblivious scientists (and eventually, executives) at the story’s core exploit their discovery for ever-more unethical purposes, the ripple effects of their deeds radiate outward in surprising manners, claiming unsuspecting victims, and culminating in a terrifying grand finale. It isn’t one of the official puzzles of the game, but piecing together the game’s timeline and understanding how its characters influence each other in unforeseen ways is yet another means by which Rise of the Golden Idol excels as a compelling, gratifying mystery, making it a more than worthy successor to an already excellent game.

This page was created programmatically; to read the article in its original form, you can go to the link below:

https://www.lawyersgunsmoneyblog.com/2024/12/gaming-notes-6

and if you wish to remove this article from our site, please contact us