This page was generated automatically, to access the article in its initial site you can visit the link below:

https://www.acsh.org/news/2024/12/30/does-lifestyle-medicine-empower-physicians-49207

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website please get in touch with us

A recent publication praised Lifestyle Medicine training as a means to “enhance” physicians through education. However, a deeper examination of the study shows modest knowledge improvements, inflated self-assurance, and minimal evidence that it leads to changes in practice. Let’s explore just how empowering this training truly is.

A recent headline stated, “Lifestyle medicine education empowers clinicians.” The article centered on a newly released paper in the American Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. The report mentioned

“The findings are significant because, while changes in lifestyle behaviors are frequently the ideal treatment option in clinical practice guidelines for noncommunicable chronic illnesses, numerous clinicians refer to their lack of knowledge and training in lifestyle behavior interventions as an obstacle.”

Examining the paper highlights the challenges of science journalism and how easily one can depart with an incomplete understanding. Let’s delve into the study to ascertain what it examined and what conclusions it reached.

The Study

This research utilizes a straightforward pre-post survey design focusing on knowledge, confidence, and attitudes after completing an LM training program. No claims can be made regarding whether or how physicians altered their practice since this investigation did not explore that aspect whatsoever. It simply assessed: “Did participants indicate that they had learned more, altered their attitudes, or confidence.” Survey responses were collected on a five-point scale, with higher scores reflecting greater confidence, knowledge, or positive attitudes.

Pre-course overall LM knowledge and confidence ratings averaged 3.21 and 3.22 (out of 5). Post-course, there were statistically significant enhancements, with knowledge increasing by 0.47 points and confidence by 0.53 points.

Most individuals entered the program with a reasonable baseline since the average overall knowledge rating was 3.21 out of 5. The average participant’s score moved just under half a point on the knowledge scale, resulting in an average knowledge rating of 3.678 out of 5 after the training – a modest rise.

Knowledge, Confidence, Attitudes

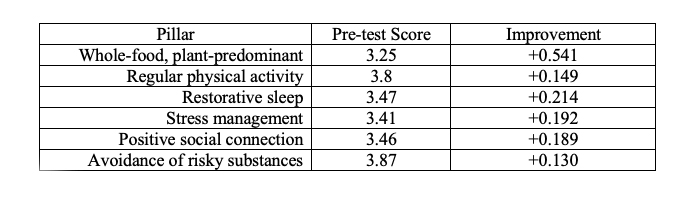

The knowledge physicians acquired from pre to post-course scores across the six pillars of LM were all statistically significant. Nevertheless, there exists a distinction between statistical and practical significance.

Most fields displayed slight improvements, roughly 5% compared to the baseline pre-score; only “avoidance of risky substances” reached a 4, but it started at nearly 3.9. Based on these survey results, practitioners’ understanding of lifestyle medicine’s pillars began and persisted as average.

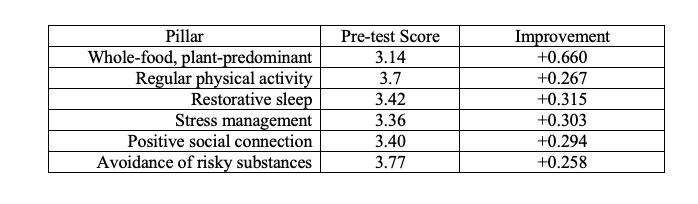

What about their confidence in discussing these topics with patients?

Confidence gains were generally somewhat more pronounced than those in knowledge. However, despite being statistically significant, the change is not substantial. The most notable growth in knowledge and confidence occurred regarding the “whole-food, plant-predominant diet.” The training elevated the weakest area in knowledge and confidence to a moderate level, which is not negligible – just above average. Confidence does not seem to present an issue for physicians.

LM is promoted as an excellent method to prevent and address noncommunicable chronic illnesses, and the study queried physicians about their attitudes regarding this matter. Initially, the positive response to “Likely to provide LM for prevention of chronic disease” commenced very high, at 4.79 out of a possible 5. It declined, at least statistically, after training to 4.72. I would contend that no significant change occurred here, although the minimal impact of training was in the opposite direction.

What Did We Learn?

This study leaves us with limited insights. It does not enhance our understanding of LM. Participants appeared to possess a solid baseline of knowledge, confidence, and attitudes, while the LM course barely shifted any indicators. The most prominent change was in the dietary category, which was the weakest area overall. It’s unclear if any individuals who underwent the training altered their practice. The survey suggests little knowledge was acquired, that confidence surpassed knowledge gains, and there was virtually no shift in the intention to change practice.

All of this seems quite distant from the “empowering” headline.

Individuals involved with the American College of Lifestyle Medicine in creating and executing a continuing medical education syllabus should not be considered newsworthy. Does LM education “empower” physicians? That’s an overstatement. The news article insinuated, without evidence, that physicians identify a knowledge and training deficiency as a barrier to practicing LM. These survey results indicate that knowledge does not pose a significant obstacle and that this training did not considerably alter intentions or attitudes. When beginning with a relatively elevated baseline in these areas, it can be challenging to shift even higher.

The authors conclude:

“The ACLM Essentials course is a cost-effective and scalable tool to provide moderate increases in LM knowledge and practice to extensive and diverse groups of healthcare professionals. Health systems aiming to enhance LM implementation can advocate this program as a component of a broader strategy that also tackles cultural and environmental barriers to LM practice.”

Yet, according to their findings, knowledge, confidence, and attitudes are not particularly problematic for the practice of LM. What then are the actual obstacles to practicing LM? I would argue that LM, operating within the public health framework, presents an individual-level solution to predominantly systemic issues. We place excessive expectations on physicians to resolve every issue for us, which is not only unjust but also sets them up for failure. An article from the British Journal of General Practice articulately conveyed this,

“Given this context, we emphasize the unintended outcomes of uncritical endorsement and application of lifestyle medicine, which include the infiltration of pseudoscience, profiteering, and the potential to exacerbate health inequalities by maintaining a predominant focus on the ‘individual.’ We urge a greater emphasis on public health and community-level interventions as well as a more critical perspective on current practices.”

I wholeheartedly support the discussion of beneficial lifestyle habits and choices with patients, but these dialogues largely overlook individuals’ collective realities. This is not a challenge physicians can resolve, nor should we expect them to. LM represents less an advancement in medical practice, and more the progression of the notion that these matters, along with other social determinants of health, can and must be remedied at the individual level. This perspective misses the broader issues at play.

This page was generated automatically, to access the article in its initial site you can visit the link below:

https://www.acsh.org/news/2024/12/30/does-lifestyle-medicine-empower-physicians-49207

and if you wish to have this article removed from our website please get in touch with us